Aise Aise Hai

NOTE: This work is an oral history and is best experienced read out loud.

First, there is the walk.

Then, there is the river, a dark salt line cutting through the city.

It is mirrored in my memory by the nadi that is home,1 light-filled and fuzzy.

There is the blue house overlooking the river,

There is the yellow house where on a good day you can hear the sea.

There is the red house on Darug country.

There is my maama saying aise aise hai to my mum… 2

Is it, is it all there is?

Is this the way it is meant to be?

That it has to be this way?

Aise Aise Hai, when translated from Fijian Hindi, is a phrase that speaks of destiny.

In a scene from Mohini Chandra’s Kikau Street, a woman holds a mirror reflecting the sky to let those on the other side of the river know it is time to be picked up and come home.3 In my mind, my hand holds that mirror, and I am letting my father know how far I have come. Of the distances, his footsteps have led mine. I am letting my uncle know that maybe this isn’t always how it is meant to be.

In many ways, my walk to the Thames in London, where I lived when I wrote this, is mirrored in the walk my father did barefoot as a child from my Aaji’s house in Yalava to Sigatoka Town, following the Sigatoka nadi to get an education.

I am perpetually following the footsteps of my elders, from Girmit to Teacher to Artist. Knowledge holders. Holders of history.

Aise Aise Hai suggests that we can move across distances and still carry home with us. Our bearings are geo-located and cached in us. Our caches contain small histories that can be returned to and reimagined if given enough data and care, enabling us to find our futures.

This work is for my family to remind us of how far we have come.

—

I am remembering eighty-seven ships sailing black waters.

60,965 bodies moved through the kala pani, the dark tides.

“Talanoa is a traditional word used in Fiji and across the Pacific to reflect a process of inclusive, participatory and transparent dialogue. The purpose of Talanoa is to share stories, build empathy and to make wise decisions for the collective good.”4

This is the foundation of my context. I am a Pacific Artist of South Asian descent. However, while living in London, I write these words while enrolled in a Masters at Goldsmiths University. In other words, I am in an institution and context that will probably have never heard of or want to know my history. How does one navigate this void? How does one make art in the company of thieves? How does one remember that they are a body with capacity and not just a colonised body with histories that are not allowed to exist? Or histories that reflect singular and non-complex ways of being. Is it possible to reclaim this body and, with it, remake what has been lost into love?

Holding land in their bodies, mere porvaj

Only 60 553 arrived in Viti.

In Ross Gay’s essay “Be Camera, Black Eyed Aperture,” he states: “if we make the brutal the ground of our imaginations, of our poetic lives, we come to need the brutal. I want to say that again: if we make the brutal the ground of our imaginative and poetic lives, we will come to need the brutal for our poetic and imaginative lives. This is neither good for our poetry nor our souls nor each other.”5 In essence, Gay questions if one needs trauma to make artwork or if it leads to the repetition of trauma. As a person whose history is attached to Girmitiya indentured labour, post-slavery and the forced movements of bodies, Gay’s provocation guides how I practice. I am seeking ways to speak of history without invoking cycles of violence. I am looking for alternative frames to allow a community to be accounted for. We are allowed to exist in plain sight and be visible in sites with little knowledge of us, which are responsible for our displacement in many ways. Is it possible to build a memorial that reveals our story?

I am remembering those who fell,

Those who couldn’t make it across to that better life of false promises.

“There is gulf of distance between viewing the Pacific as ‘islands in a far sea’ and as ‘a sea of islands.’ The first emphasises dry surfaces in a vast ocean removed from the centre of power. When you focus on this way, you stress the smallness and remoteness of the islands. The second is a more holistic perspective in which things are seen in the totality of relationships.”6

Epeli Hau’ofa’s above words critically engage with the idea that the Great Ocean, the Pacific, is an archipelago connected by the sea; the sea is the site of connection, not isolation, as suggested by the Western lens. I am reclaiming my archipelago by reimagining the oceanic gaze within my work. I am creating my own sea of islands by retracing a route through time, following my father’s footsteps—an archipelago made through a material understanding of relationships, place, and story. I am translating and reimagining history, hoping the memorial will be reframed.

—

A STONE IS PICKED UP.

Since October 2020, I have been walking towards this nadi. It began as a way to mark time and map myself into London—a way-finding tool. However, instead of waterways, I use roads and birdsongs.

It wasn’t supposed to be the work.

It makes sense, though. The river holds aeons of history.

I have 142 years.

How much history does a river stone hold?

—

Pani begets pani.

In the poem “The First Water Is the Body” by Natalie Diaz, she states:

“I carry a river. It is who I am: ‘Aha Makav. This is not metaphor.

When a Mojave says, Inyech ‘Aha Makavch ithuum, we are saying our name. We are telling a story of our existence. The river runs through the middle of my body.”7

Before arriving in London, I would have told you that the water that informs my work is the kala pani [the black waters]. A taboo suggests that when a South Asian body leaves India, they are no longer tethered to land. An ocean of black water that dissolves ties to history and place. A body of water that unties knots of understanding to the Indic plain and ties my ancestors and myself to colonial tethers of empire and queen.

In London, the water I am learning is the Thames. The word I use for a river is nadi. The nadi is both a point of departure and arrival. It feels essential to think of the word arrival; in walking towards this river, I am arriving at history. Here, I feel echoes of my personal journey, along with the historical journey navigated by my ancestors, which connects me to Greenwich, a place of empire and time. I think about Island time here. The schism between the Island I long for, Viti, and the place I am in, England. This is the wrong island—the wrong time. My island time is in the new day; by moving backwards, I am proposing a space that allows my community’s stories to be held and told.

They say that to feel grounded in a new place, it is best to stand on land. To learn a place is to learn its name. The Thames means darkness or dark one in proto-Celtic and Sanskrit.89 In learning the river’s name, I am speaking things to existence. I am calling towards the future; I am reimagining the past. I see the line being made by this dark river that connects to the Kala Pani. I can see the data constructing my personal cache and am rerouting it with intention.

Dark water begets black pani.

—

An archipelago is defined as a group of islands or an area of sea with many islands.10

“Sleeping on our mother’s breasts

Gave breath and bread to an island

And like islands in an ocean

Shipwrecked, trapped in history

Without the grammar of grandmother”11

In Satendra Nandan’s 2007 poem ”Lines Across Black Waters,” he speaks of islands as ruined histories that need the language of elders for a person to navigate their story.

—

After speaking of the river and its stones.

We must speak of music, of Qawwali.12

In 2017, in Mumbai, I met Rahaab Allana, a critical writer and thinker of photography in South Asia. In his talk at the Bhau Daji Ladd Museum, he spoke about Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh, a sight of extraction for the Indentured Labour community. He said there are places in Lucknow: places of water where you can visit that are sites of Qawwali. Qawwali is a musical form of call and response. You can visit Qawwali sites and ask the water questions, and the water will respond.

The walk is the call, the stone a response.

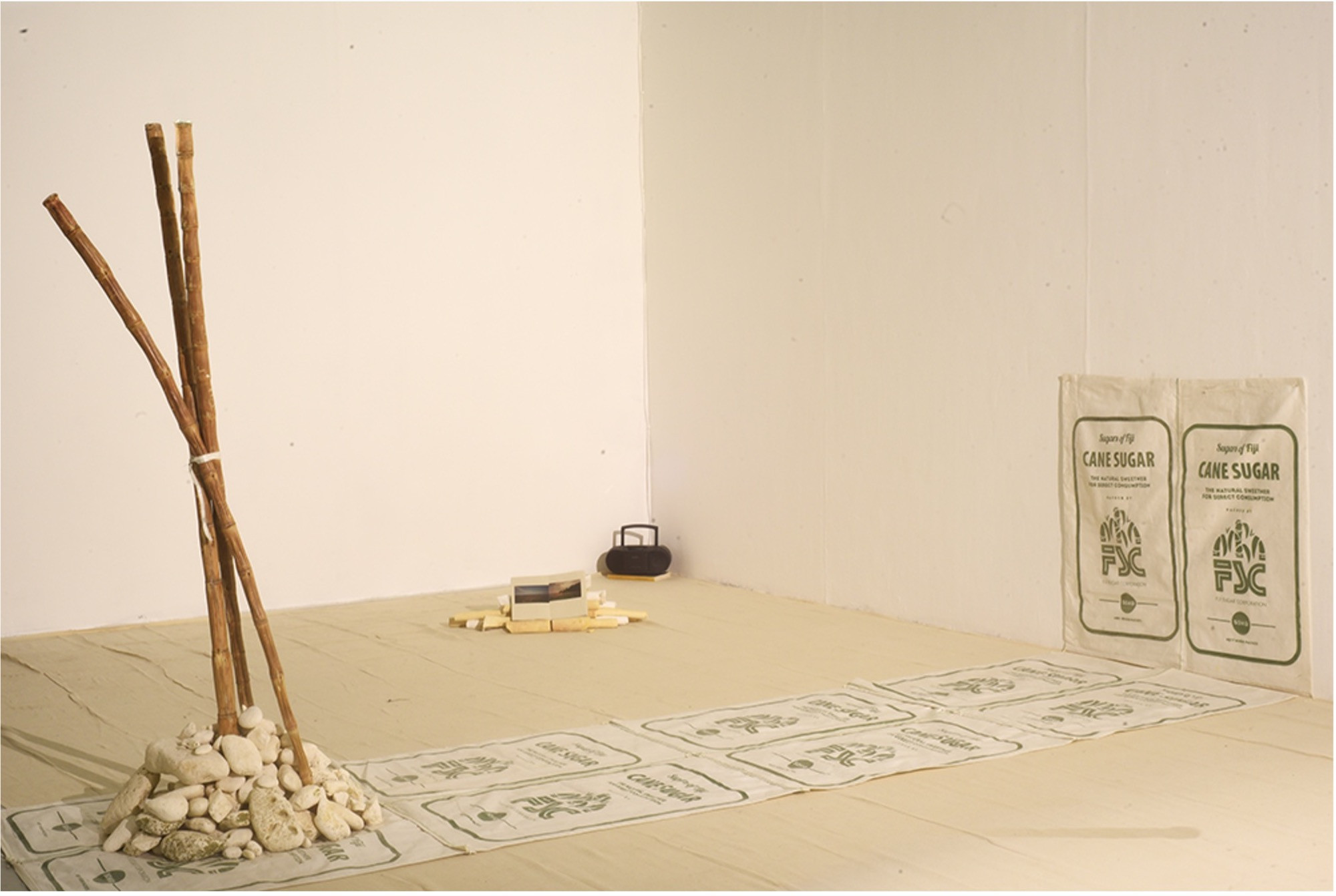

I have tried other ways to mark time. Collecting stones has become a way to account for these trips to the river. The stones feel right. When I began collecting stones, I wasn’t choosy, but now I only seek white stones—chalk stones, to be specific.

—

Chalk has its own social, political, and artistic history, which I intend to map in this essay.

Geologically speaking, chalk is made up of calcium. It is a sedimentary carbonate formed 85 million years ago. It has many uses, including altering soil Ph. This is significant because this idea of alchemy and balancing feels like an unintended but vital outcome of my work.13

When I think about soil, I always think of my dad and his beloved garden. I believe that he would be most proud of me if I learned how to grow tomatoes. This may not happen, but these stones are the tomatoes I will never grow.

Reclamation is making land underwater or in poor condition suitable.14

Seven islands on the Arabian Sea, known only to Koli fisher people off the Konkan coast, get caught between two empires, the Portuguese and the British. A dowry of islands was gifted between them (no consultation required by the locals) in 1661 and offered to the East India Company to make a go of it for ten pounds annual rent.15

The islands are filled in to form a harbour. A reclamation occurs. Stones fill the spaces between. A city of dreams is made, known as Bombay to its locals. Every time it rains, it falls apart.

In collecting stones, I am reminded that this is a foundational material. That it is of the land. In collecting stones by the river, I may be the first to hold this stone. The stone is imbued with more meaning. In carrying the stone from the river to the studio and later to a gallery, I create a line and an intention. This line mirrors the one my Barra Nanni did from Kolar to Ba, my father did from Yalava to Sigatoka, and I did it from Sydney to London. This stone has moved into my hands through the river and has become art.

—

Seventy-one rocks sourced in Gunditjmara country in so-called Australia form Hayley Millar Baker’s work Meeyn Meerreeng. Painted black to hide their identity, the works are only allowed to be held by Indigenous peoples, and if there are no Indigenous people to care for the work, the work is not allowed to be shown.16 The work references land in its rawest form. However, through each incarnation, something new is revealed, and it becomes entangled in the landscape of its location. It responds to the hands that have held it.

I feel this idea of care; no one but me is allowed to carry the chalk stones or contribute to the pile of stones. I have a duty of care toward these stones, and it is my responsibility to hold them like I would my family.

In my first attempt at caring for them, I covered them with turmeric. This did not feel right. My second attempt was to try and string them up to turn them into a mala (garland). However, deforming the stones again felt wrong. It felt important that the stones remain whole as they were found. The act of holding and moving them through the land was enough.

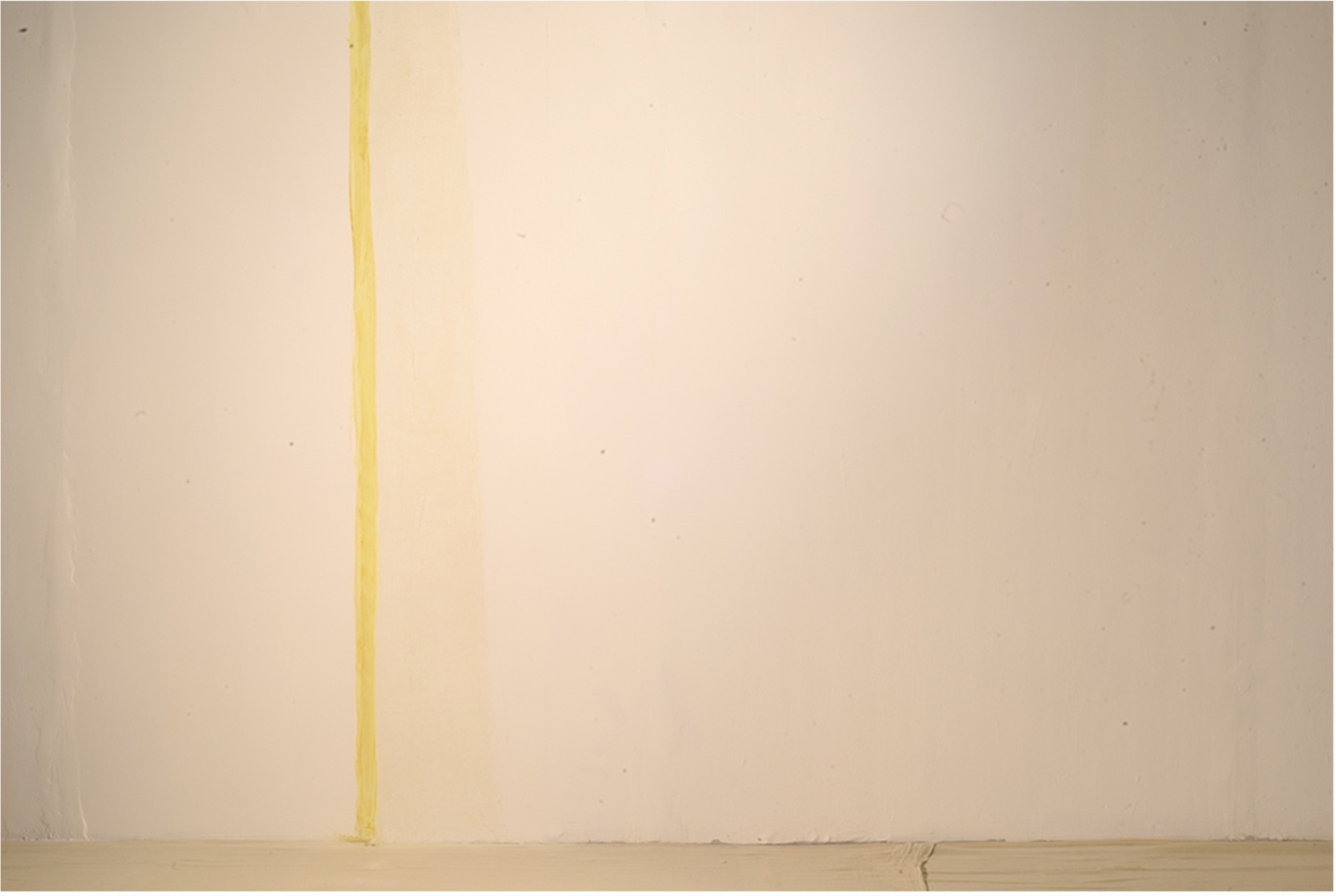

Carrying them with care and using chalk as drawing material is a rudimentary but primary purpose of chalk in education. Using chalk in its foundational use is a move towards forming a memory work that could be interpreted as an action for remembering. Situated somewhere between temporary and temporal, I drew a line that felt like an echo of a monument. A reminder of things that are allowed to exist in plain sight for the few but not for the many.

In the shadow of sugarcane lies this great, big history.

Similar to a line drawn in the sand. This time up against the wall.

Temporary and temporal.

—

A year ago, I started a new map project. I am obsessed with maps. One map called the Australian Hemisphere haunts me. Although it includes India and Fiji, it centres Australia and, for me, localises the impact of colonisation on my region. This hemisphere holds India, Fiji, and Australia, and I cannot be here without any of those places.

I asked my mum if she had a sari. My mother is constantly attempting to rid herself of her saris, as though she is convinced no one will want this bodily history of hers when she passes.

I had been unsuccessfully trying to get my mother to help me stitch throughout April and May of 2020. I thought our busy hands would take our minds off the things that were on our minds.

We begin to stitch a large map onto a sari. I bring this sari from Sydney to London and spend weeks stitching eighty-seven lines through paper and silk. I finished doing this in the middle of May 2021, around the same time as the 142nd anniversary of the first ship arriving carrying indentured labourers from India to Fiji. It felt right to stop the work then.

I moved the work from my living space to my studio, and something changed.

I could no longer look at the work.

It felt not enough and simultaneously too much.

Who cares about red lines stitched through paper and silk?

Was this all a waste of time?

Was this labour of any value?

Feeling lost, I folded the sari and put it away.

Sometimes, things don’t make sense until they are put away.

Maybe what was valuable was the labour unseen.

Something is revealed in the unseen.

—

As a teenager, my mother would print out the bad poetry I wrote and share my words with strangers. It stopped me from writing. Returning to writing all these years later and asking her to collaborate with me is something that has happened in this work.

In Mirene Arsanio’s Notes on Mother Tongues (2020), she states, “My language speaks many languages—French, Italian, Arabic, Spanish and English— none of which I can call home. Like other languages originating in histories of colonisation, my language always had a language problem, something akin to the evacuation of a ‘first’ or ‘native’ tongue—a syntax endemic to the brain and to the heart.”17

I speak my colonisers’ language better than my mother tongue. My tongue holds language neither native nor in close proximity to my heart. I cannot write at all in my mother tongue. Amma’s translation offers me possibilities. While I can speak a sentence together in Fijian Hindi, hers is still capable of writing and transmuting it across the distance that exists between us. In asking my mother to translate, I am asking her to return my words to a nascent part of me, the heart of me. I am asking to form a new foundation in this place that is foundational but simultaneously foreign.

In many ways, these acts of translation between her and me are reclamations—a stockpiling of words in lieu of stones to build a new foundation on which a life can be seen, heard, and witnessed.

—

There is no return or returning.

Only actions to remember.

Reading here becomes an act of recollection.

A live reading is a soundscape that cannot be pinned down. It is my voice and the river that forms the live reading. The untethered, unseen membrane connective tissue that holds all the works in Aise Aise Hai together connects two places simultaneously: the river and the exhibition space. In the exhibition space, my mother’s voice and my words continue to construct a soundscape in situ, floating light as air. A line is made. This is the birdsong holding my archipelago together.

—

Who is winning here, stones, water or land?

I have a complex relationship with place. I am situated somewhere between Vanua and Desh. Vanua is an iTaukei term for land, and Desh is the equivalent in Sanskrit.18

I have to consider the role these understandings of land have grounded the way I have moved and mediate my body through London.

“When I think about the future, I think about a place where I can create stories that have not been colonised, in the sense that my present is very much controlled by our history. Romanticising, my own sovereignty is a place in time where we can imagine solutions to colonisation and ways that are better for Indigenous peoples.”19

Considering Hannah Donnelly’s thoughts, as spelt out above: I am conscious in moving through London I am navigating time and history prescient of all its faults. The British colonised and moved my family. I can change how I allow that experience to be recollected. In reimagining my family’s story, I am navigating sites of geolocation and creating possibilities for my community that have the capacity to shift perception. This land is no longer sovereign; my body includes an understanding of Vanua and Desh. Thus, through this, I ask: remember us.

—

I am remembering the valley road

Ganna fields whipping past on one side, the river on the other

Silver and serpentine capturing light

I only think of this body of water, never the saumandar when I think of home.

I remember that I have no memories of my birthplace, only ones that I made after leaving.

My hand is in Aaji’s as we walk the shoreline of Korotogo.

The aam is made sweeter with chilli and salt

Her box was full of letters, with mine on top

The flower curtain holding the wind like a breath

—

It’s hard not to think of chalk and not think of chalkboards and the slow removal of knowledge resurfacing as dusty residue. A cycle of knowledge built over and lost.

How much history does a chalkboard hold?

My first memories of my Aaji are of her holding my hand as she walked me and my brother to school. She and my Nanni would steal flowers on the way to and from the red house. My mother called them flower thieves and joked about calling the police. I’d come home and find roses and hydrangeas smuggled and proffered to our gods in the Puja place.

Are ill-gotten flowers an appropriate offering for the Gods on stolen land?

—

A nadi, a river

An echo, a mirror

A reminder, a memorial, a longing for home

On the wrong island, the wrong river

I sing out this prayer

No flowers, just stones, just bones

—

The word mudlark means to scavenge for goods on riverbeds.20 Am I a good mudlark, or a bad mudlark? I often ask myself by the river. Are the stones I find something that can be witnessed as valuable? Or do they go the way of broken bones?

In 2012, SJ Norman created a dictionary of lost Indigenous words. Carving each word into the bones of cows and sheep, the pastoral disruptor of Indigenous lands. A Bone Library was formed; this library was then offered to the community as an act of custodianship. Without knowing me, SJ gave me the word grandmother to look after.21

It was a sign—a reminder that if the work I make is important, then it honours the relationships that are at the heart of my life: my Aaji and Nanni: Bindumati Narayan and Puniamma Arumugam.

—

In 2016, Jonathan Jones made Barrangal Dyara (skin and bone). The work uses fifteen-thousand bleached white shields to create the outline of the Garden Palace, where the Sydney International Exhibition was hosted; the Garden Palace was built in 1879, coincidentally the year of the first ship arriving in Fiji with indentured labourers from India, and lost to fire in 1882.22 The fire destroyed a collection of South Eastern Aboriginal cultural artefacts along with important Pacific objects. The work uses the void space of the collected shields to house language and song. As one wanders through the space of what is left behind, they encounter the voices of elders singing and children laughing and learning. The great strength of this work is that it plants seeds for the future.

It honours the relationship between memory and language and reminds me that when we speak language, we have the tools to keep remembering. We have the capacity to speak things into existence.

—

Why is it, then, when dipped in water, chalk has more staying power?

In 2013, I took my mother to see an exhibition by artist Jitesh Kallat at the Ian Potter Museum of Art in Melbourne. The exhibition Circa moved me, and even though I can count on one hand how many exhibitions my mother and I have seen together, it felt important that I take my mother to see this exhibition.

In the anthropological wing of the Potter, Kallat had collected South Asian temple paraphernalia and placed them behind glass. On the vitrines, he drew bullet holes and broken glass using white chalk. A relationship was formed between the object and the violence of its gathering that, for me, could not be unseen. In bringing my mother to the exhibition, I wanted to be reminded of the living, of the reasons we build stone idols, of the hope that remains in the body.23

In his poem: “Seeking the Beloved,” Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai (1689–1752) says:24

To choose safe waters

Is the route of imposters:

Those who love

Take on the mighty river

I think of these lines often when I am at the Thames, a moving, unknowable salt line that changes with the moon. I think Bhitai is saying that in love, we need to be brave, that in love, we need to speak, and that in love, we need to remember.

—

I have remembered those who fell,

This is the better life we were promised,

60,965 bodies moved through the kala pani, the dark tides.

Leaving Desh, moving towards Vanua.

Holding land in their bodies, mere porvaj

Only 60,553 arrived in Viti.

Eighty seven ships sailing black waters.

—

What I know to be true is this work is about love. Love for my family, love for our story and our potential. In writing this text, I am writing a history of my own. It does not make ghosts of my ancestors. These are people with fully lived lives who I am remembering. Worthy of being memorialised. It is easy to discount a life, especially one that has never been allowed to be visible. It is much harder to make things about the poetics of living, such as the walk my father did barefoot as a child from home to school.

From Girmit, to teacher, to artist. A knowledge holder, a holder of history.

—

They had birds and fishes under their skin.

Papery and translucent, as though they would disappear when they slept at night.

Disappearing into their blood only to return in the morning.

I used to trace the lines of initials and flowers, wondering how they got etched onto my grandmothers’ bodies.

It was a comfort to see marks so lived in.

I imagine dark nights and laughter ringing out as their marks were made.

Imperfect and fragile, when I touched them, I felt whole histories.

—

In the Fijian Hindu tradition, I am familiar with, how we take our ashes and bones to the Saumandar. We do not have graves to visit. Instead, we take an image of the ones we love and place a mala around them—a garland of small stones embracing the photograph—holding it with care, protected by our love and prayer.

In the future, will someone hold a stone and wonder whose ancestors constructed it?

-

English-Fiji Hindi Dictionary, “nadi,” last modified February 3, 2008, oocities.org/fijihindi/FijiHindiEnglishDict.htm. ↩

-

English-Fiji Hindi Dictionary, “maama.” ↩

-

Mohini Chandra, “Kikau Street, 2016,” accessed August 30, 2021, mohinichandra.com/about-kikau-street. ↩

-

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Talanoa Dialogue Platform, 2018, accessed July 25, 2021. unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement/2018-talanoa-dialogue-platform. ↩

-

Ross Gay, “Be Camera, Black-Eyed Aperture,” The Sewanee Review (Winter 2021). Accessed August 25, 2021. thesewaneereview.com/articles/be-camera-black-eyed-aperture. ↩

-

Epeli Hau’ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” The Contemporary Pacific 6, No. 1 (Spring 1994): 148–161. ↩

-

Natalie Diaz, The First Water is The Body (London: Faber & Faber, 2020). ↩

-

Online Etymology Dictionary (2001–21), “Thames,” accessed August 30, 2021, etymonline.com/word/thames. ↩

-

Peter Schrijver, Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1995). ↩

-

Cambridge Dictionary, “Archipelago,” accessed August 25, 2021, dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/archipelago. ↩

-

Satendra Nandan, Lines Across Black Waters: The Loneliness of Islands Collected Poems 1976–2006 (Fiji: Ivy Press International, 2007). ↩

-

Rahaab Allana, “Photography in India: 1850–1947,” lecture at Mumbai: Bhau Daji Ladd Museum, April 28, 2017. ↩

-

Helen Gordon, “Rock of Ages: How Chalk Made England,” The Guardian, February 23, 2021, theguardian.com/news/2021/feb/23/rock-of-ages-how-chalk-made-england-geology-white-cliffs. ↩

-

Srinath Perur, “Story of Cities #11: The Reclamation of Mumbai—from the Sea, and Its People?” The Guardian, March 30, 2016, theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/30/story-cities-11-reclamation-mumbai-bombay-megacity-population-density-flood-risk. ↩

-

Perur, “Story of cities #11.” ↩

-

Hayley Millar Baker, Void & the Undefined, 2019 (Sydney: Museums & Galleries of NSW, 2021), mgnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Void-Learning-Resource-online.pdf. For exhibition Void first held at UTS Gallery from 25 September to 16 November 2018. ↩

-

Mirene Arsanios, Notes on a Mother Tongue: Colonialism, Class, and Giving What You Don’t Have, (New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020), 1. ↩

-

Aubrey Parke, “The Ideological Sense of Vanua,” in Degei’s Descendants: Spirits, Place and People in Pre-Cession Fiji,” Matthew Spriggs and Deryck Scarr eds. (Canberra: ANU Press, 2014), 27–36, jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13www1w.9. ↩

-

Hannah Donnelly, “Indigenous Futures and Sovereign Romanticisms. Belonging to a Place in Time,” in Sovereign Words: Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism, Katya García-Antón ed. (Amsterdam: Office of Contemporary Art Norway/Valiz, 2018), 268–9. ↩

-

Jason Cochrane, “Mudlarking in the Thames Might Be The Best Thing I’ve Done in London,” Frommer’s Travel Guides, accessed April 18, 2021, frommers.com/slideshows/848024-mudlarking-in-the-thames-might-be-the-best-thing-i-ve-done-in-london text: https://www.frommers.com/slideshows/848024-mudlarking-in-the-thames-might-be-the-best-thing-i-ve-done-in-london). ↩

-

SJ Norman, “Bone Library, 2012,” accessed April 14, 2021, sarahjanenorman.com/bone-library. ↩

-

Jonathan Jones, “barrangal dyara (skin and bones), 2016,” accessed August 28, 2021, kaldorartprojects.org.au/projects/project-32-jonathan-jones. ↩

-

Jitish Kallat, “Circa, 2012,” accessed April 18, 2021, art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/exhibitions/jitish-kallat-circa. ↩

-

Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai cited in Parineeta Dandekar, “Rivers Are Us, 2018,” accessed April 13, 2021, sandrp.in/2018/02/17/rivers-are-us. ↩

Shivanjani Lal is a Fijian-Australian artist and curator whose work uses personal grief to account for ancestral loss. Recent works have used story-telling, objects and video to account for lost stories of Girmitiya (Indenture) from the Indian and Pacific oceans. Truth-telling and monument making has become a focal point of her current research in an attempt to decipher what is lost and the possibilities of futures. Between 2017-18, Lal sought to globalise her practice with a prolonged stay in India, which led to periods of research in Nepal, Bangladesh and Fiji. She was the 2019 Create New South Wales Visual Arts Emerging Fellow, and the 2020 Georges Mora Fellow. In 2021 she graduated with distinction from Goldsmiths, University of London with a Masters in Artists Film and Moving Image. In 2023 she received the QAGOMA Vida Lahey Scholarship. Lal’s work has been exhibited across Australia, and internationally.

Bibliography

- Allana, Rahaab. “Photography in India: 1850-1947.” Lecture, Mumbai: Bhau Daji Ladd Museum, April 28, 2017.

- Arsanios, Mirene. Notes on a Mother Tongue: Colonialism, class, and giving what you don’t have. New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020.

- Chandra, Mohini. “Kikau Street, 2016.” Accessed August 30, 2021. mohinichandra.com/about-kikau-street.

- Cochran, Jason. “Mudlarking in the Thames Might Be The Best Thing I’ve Done in London.” Frommer’s Travel Guides. Accessed April 18, 2021. frommers.com/slideshows/848024-mudlarking-in-the-thames-might-be-the-best-thing-i-ve-done-in-london).

- The Hours, Directed by Stephen Daldry. 2002; Los Angeles, CA: Miramax. netflix.com/au/title/60025007.

- Dandekar, Parineeta. “Rivers Are Us (2018).” Accessed April 13, 2021. sandrp.in/2018/02/17/rivers-are-us.

- Diaz, Natalie. The First Water is The Body. London: Faber & Faber, 2020.

- Donnelly, Hannah. “Indigenous Futures and Sovereign Romanticisms. Belonging to a Place in Time.” In Sovereign Words: Indigenous Art, Curation and Criticism. Edited by Katya García-Antón, 268-9. Amsterdam: Office of Contemporary Art Norway/Valiz, 2018.

- Gay, Ross. “Be Camera, Black-Eyed Aperture.” The Sewanee Review (Winter 2021). Accessed August 25, 2021. thesewaneereview.com/articles/be-camera-black-eyed-aperture.

- Gordon, Helen. “Rock of ages: how chalk made England.” The Guardian. Published February 23, 2021. theguardian.com/news/2021/feb/23/rock-of-ages-how-chalk-made-england-geology-white-cliffs. - Hau’ofa, Epeli, “Our Sea of Islands.” The Contemporary Pacific, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring 1994): 148-161.

- Jones, Jonathan. “barrangal dyara (skin and bones), 2016.” Accessed August 28, 2021. kaldorartprojects.org.au/projects/project-32-jonathan-jones.

- Kallat, J. “Circa, 2012.” Accessed April 18, 2021. art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/exhibitions/jitish-kallat-circa.

- Millar Baker, Hayley. “Void & the Undefined, 2019.” Sydney: Museums & Galleries of NSW. Accessed July 28, 2021. mgnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Void-Learning-Resource-online.pdf.

- Nandan, Satendra. Lines Across Black Waters: The Loneliness of Islands Collected Poems 1976-2006. Fiji: Ivy Press International, 2007.

- Norman, SJ. “Bone Library, 2012.” Accessed April 14, 2021. sarahjanenorman.com/bone-library. - Perur, Srinath, (2016) “Story of cities #11: the reclamation of Mumbai – from the sea, and its people?” The Guardian. Published March 30, 2016. theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/30/story-cities-11-reclamation-mumbai-bombay-megacity-population-density-flood-risk.

- Parke, Aubrey. “The Ideological Sense of Vanua.” In *Degei’s Descendants: Spirits, Place and People in Pre-Cession Fiji.” Edited by Matthew Spriggs and Deryck Scarr, 27-36. Canberra: ANU Press, 2014. jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13www1w.9.

- Schrijver, Peter. “Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology.” Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1995.

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Talanoa Dialogue Platform, 2018. Accessed July 25, 2021.

unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement/2018-talanoa-dialogue-platform.