Spectropolitics and Invisibility of the Migrant On Images that Make People “Illegal”

Introduction

“To see is to believe” and “out of sight out of mind” are just two sayings emphasising the extraordinary power of our brain to focus only on what is visible.1 Once the subject of our visual attention is removed from our gaze, its importance usually wanes and other issues “right before our eyes” require more attention. In this article I will challenge these assumptions when it comes to the contemporary figure of the asylum-seeking refugee. I will demonstrate that when it comes to refugees, invisibility—or a certain form of it—can result in a more powerful response from the viewer than a visible figure can. To illustrate this invisible figure of a refugee, I will focus on two governmental campaigns—one on Australia and one in the UK—that present an invisible refugee and portray them as “illegal.”2

While governmental poster campaigns are usually released to inform the community, direct the community to appropriate resources or announce important changes, I will show that when the subject is contemporary refugees, the impact far exceeds this typical function and is more akin to war propaganda posters. These depictions differ from typical information posters such as those announcing elections, changes in local laws or openings of public initiatives. Governments and public authorities increasingly use visual campaigns for entirely new purposes justifying unprecedented legal initiatives related to border control. Some of these campaigns have become subjects of heated discussions, which rarely occur when it comes to typical public posters.3 This is partly due to the fact that new kinds of visual campaigns analysed here have been used by authorities to directly target refugees in order to deter them from arriving, staying or claiming asylum.4 While allegedly speaking to refugees, these posters replace the image of the refugee with visual symbols that represent the fraudulent asylum seeker. In this article I shall argue that this ghostly invisibility has an unprecedented emotive power of speaking not to refugees, but to domestic voters within host countries.

This article focuses on the figure of an invisible asylum seeker and examines how the construction of this invisibility reflects and reinforces the local population’s anxieties about migrants. The refugee is a particular type of immigrant whose movements across and within national borders are generally regulated by laws. As a former settler colony, Australia is a country of migrants that continues to seek migrants. Voluntary migrants greatly outnumber refugees and asylum seekers, but it is the latter that has dominated domestic politics and Australian changes to migrant law.

Multiple representations of migrants are possible and in Australia they have historically been positive images designed to promote immigration. There have also been positive images of refugees and asylum seekers used by NGOs and activist groups. 5 This article focuses on governmental campaigns in the context of what has been called an intensifying crimmigration related to border control due to refugees largely arriving by irregular means on boats.6 While these are not the only context in which such images of refugees arise, I will analyse two examples emerging in the Anglophone world: the Australian NO WAY campaign and British GO HOME campaign. I will show how those implicitly depicted in those campaigns are construed as ghostly entities who can be disciplined by the law but who are, at the same time, left completely outside the workings of the legal system. I argue that images that rely on what I call spectrality of the refugee leave the refugee out of the frame for a reason. The use of an image of the spectre affects the legal imagery of the community. It creates a fear of the monstrous and allows for legitimating the decisions that would otherwise be difficult to justify if not for the presence of the spectre.7 I see such play with invisibility as a part of spectropolitics, a term I borrow from Maddern.8 Related to Derrida’s exploration of spectrality, spectropolitics refers to the use of invisibility (metaphorical or visual) to expel some subjects from the community and subsequently place them outside the compass of compassion. In the context of refugees, I will show how spectropolitics are used visually to recast the boundaries of what is legally permissible in domestic refugee regulation.

The slippery nature of illegality and why it is often invisible

As a broad category, illegality characterises acts and objects deemed to stand outside the permissible boundaries of the law. Due to its broadness, illegality is itself a somewhat ephemeral and ghostly category. What is illegal is often uncertain and changeable and can be amended quickly and unpredictably.9 A sovereign can take measures to outlaw a range of activities, from simple daily routines to more morally objectionable acts. From selling alcohol, participation in suffragette protests through to murder, the historical catalogue of outlawed activities is broad. It even includes such actions as fortune-telling, banned in Baltimore,10 or being reincarnated without permission, banned in Tibet.11 What the law deems to be illegal tends to be rendered invisible, to a black market hidden from the law’s gaze. Public authorities will typically target illegality with the enforcement of criminal law and penal punishment, spanning from fines through to the harshest methods of legal violence: incarceration or even execution. Criminal law, with its penal system, is the most violent branch of the law targeting illegality. It exemplifies Derridian violence of the law in its preserving form.12

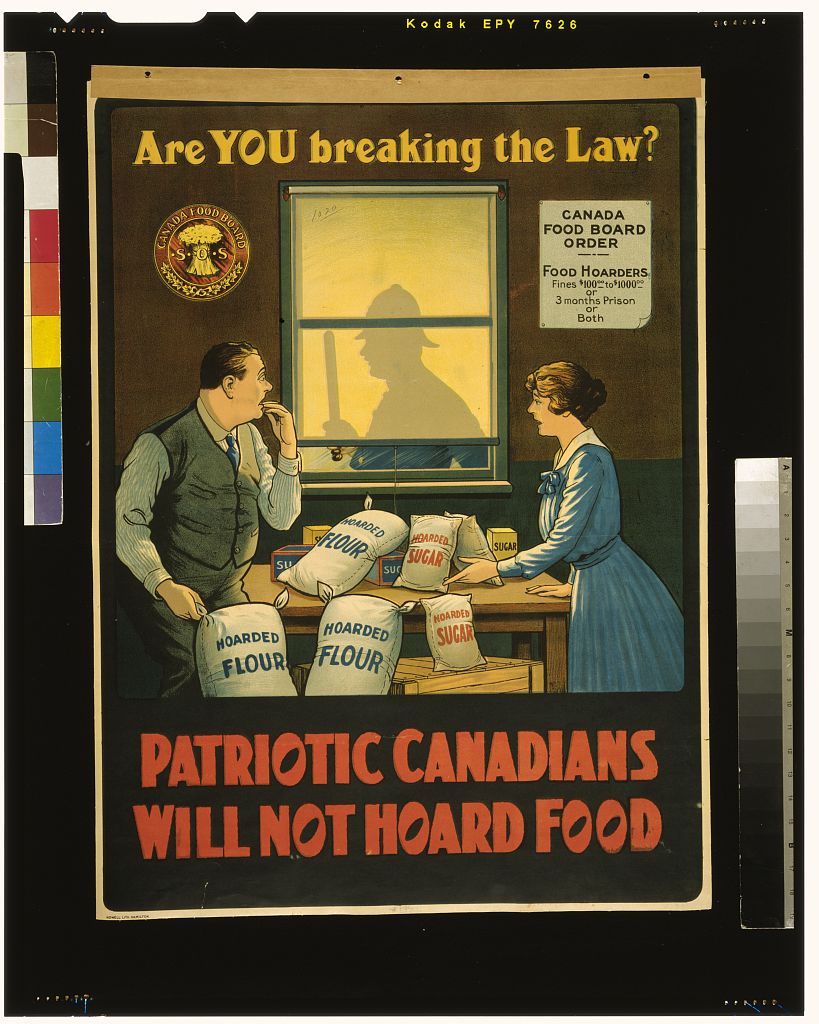

Yet, the ephemeral and quickly changing catalogue of illegal activities makes it difficult to portray illegality. Sometimes the simple use of criminal law imagery—such as representations of enforcement officers or penal methods—are sufficient. If illegality hides from the gaze of the law, the mere shadow of the law enforcement figure, such as in this WWI Canadian poster targeting food hoarders, should be sufficient in depicting it (fig. 1). In this poster, illegality is precisely illustrated by the mere shadow of a police officer outside the window. The shadow of the law signifies that, at what first glance appears to be a daily activity of organising a pantry, is in fact an outlawed activity of hoarding limited resources. The presence of the shadow of the law, powerfully communicates the fact that storing too many resources in one’s pantry during wartime is an illegal activity, regardless of whether it is visible to others. The symbol of the police officer links the seemingly innocent image of the couple sorting food with the criminal law sanction. It also captures the fear thereof in the guilty facial expressions of the hoarders. Where law casts its light, illegality can be uncovered and will not remain invisible for long.

In the context of refugees, however, illegality is only a recent concept. It was rarely used prior to the 1990s, and only took global hold as a result of discourse of bogus asylum seekers.13 Furthermore, illegality is usually used to describe forced refugees arriving by irregular (unofficial) means and without proper paperwork.14 As shown time and again, such illegality relates to border control15 and the ever more restrictive regulation of the movement of people.16 Due to the nature of their circumstances, refugees often shift between legality and illegality and scholars have avoided using the terms “legal” and “illegal” to describe any mode of arrival or any type of a migrant, refugee or asylum seeker.17 The use of the term illegal has gradually removed people from the compass of compassion and justified the use of criminal law methods in controlling the movement of people.18 Juliet Stumpf powerfully illustrated how conflation of immigration and crime management results in the appearance of crimmigration.19 Although migration law was traditionally closer to foreign policy than criminal law, the situation began to change in mid-1990s Australia and intensified throughout the Western world when border control became a domestic political issue due to the influx of refugees from the global South20. Stumpf reminds us that the merger between migration law and criminal law became possible because both are essentially connected with the process of deciding who does and who does not belong:

Both criminal and immigration law are, at their core, systems of inclusion and exclusion. They are similarly designed to determine whether and how to include individuals as members of society or exclude them from it. Both create insiders and outsiders. Both are designed to create distinct categories of people-innocent versus guilty, admitted versus excluded or, as some say, “legal” versus “illegal.” Viewed in that light, perhaps it is not surprising that these two areas of law have become entwined.21

When the other is created and a label of illegality applied, the use of criminal methods appears justified. Migrants labelled illegal are denied any sense of worthiness or the concomitant compass of compassion.22 Rather than referring to people as unregistered, for example, the tag of illegal prompts the strengthened response of migration law. Illegality encompasses anyone from a visa overstayer, a sans-papiers, or those planning their arrival in a particular manner, thereby ignoring diverse individual circumstances.23 Doing so creates a confusion about legal categories and leads to an interchangeable use of the terms “migrant” and “refugee”. Depending on the jurisdiction and local migration laws, illegality can be used as a blanket label in an extremely wide variety of circumstances. However, these various circumstances and legal categories are erased when the word illegality appears, and a migrant is put in the position of a fraudulent criminal who can be targeted with the greatest severity of the law.24

The law is justified to use more severe methods in targeting illegality than targeting irregularity. To achieve strengthened affective response legitimising harsh migration control, visual campaigns can erase the migrant from visual depiction altogether. Instead of using an image of the refugee themselves, images depicting migrant illegality are often related to depictions of unlawfulness and criminality more broadly. In those depictions the symbols of illegality often become a proxy for the figure of the migrant while the migrant themself is missing from the visual field. In those depictions, metonyms of penal justice take the refugee’s place. The removal of the migrant/refugee while retaining the symbol of their illegality implies that they haunt the legal system with their presence. Below I will analyse the spectrality behind refugee invisibility and its link with the ephemeral nature of illegality and its depictions.

Haunting the legal system—from spectrality of an illegal migrant to spectropolitics

I have so far used the words ghostly, spectrality and haunts to describe the absence of migrants and refugees from certain images about migration. The use of vocabulary associated with ghosts and the paranormal may appear to be an awkward choice. Below I will illustrate why spectrality—or the ghost-like absence of certain figures from the field of appearance—is often a more powerful emotive method of construing an image than direct depiction of the subject that the image speaks about. Using the frame to exclude the subject but retain its ghost-like presence limits the ethical response of the viewer. It recalibrates the discussion to focus on fear rather than ethics, which in turn justifies the use of exceptional methods of law response.

Spectrality, apparitions, haunting and ghosts have been used extensively by Jacques Derrida in his account of Marxist thought. In Spectres of Marx, Derrida uses the vocabulary related to ghostly apparitions to describe a certain continuity in history.25 Derridean focus on the ghost gives rise to all other considerations of spectrality. While for Derrida ghosts are related to history, for others, ghosts are related to fear. In the Derridean account the key feature of the ghost in history is its ability to haunt the future. There is in a way no before or after in this hauntology, because the ghost always threatens to return. The ghost is always there, threatening to arrive but never quite present: just like Derridean justice, always “yet to come.”26 It leaves the imprint of the past on both the present and the future. Its power lies in none other than its invisibility. While the Derridean ghost is not necessarily synonymous with exclusion it nonetheless has the potential of filling the spectator with fear of an imminent threat:

Is it the difference between a past world—for which the specter represented a coming threat—and a present world, today, where the specter would represent a threat that some would like to believe is past and whose return it would be necessary again, once again in the future, to conjure away?27

Expanding upon Derridean theory, authors such as Garoian insist that it has a meaning pertaining to the broader interplay of ontology and hauntology, or, being and not being.28 Describing the work of French artist Christian Boltanski, Garoian illustrates that this interplay will apply to the visual field, because an image—or the artist behind the image—invites the viewer to consider those who are absent from the work of art.29 In accounts focusing on the importance of absence, spectrality and hauntology signify not the potential of connection between different parts of history, but the potential of exclusion of those who are absent. For Wolfreys, spectres are those who are invisible but who nonetheless haunt the piece of art or even a piece of writing.30 Their power lies precisely in their invisibility and their hauntological exclusion applies to a broader political spectrum altogether:

Haunting—spectral persistence—imposes an impossible necessity on us: we have to be attentive to ghosts, as the work of Jacques Derrida reminds us on several occasions, and there can be no final word, no coming to rest or closure, whether one is speaking of literature or politics, narrowly conceived31.

When we understand hauntology as the exclusion of spectres from the field of appearance, we quickly realise that the ghost—although invisible—does not entirely disappear from the image. An invisible spectre continues to haunt the image with their absence rather than their presence. Removed from the image, the spectre continues to control the perception the viewer has of the image. The spectre enters the imagination of the viewer through different means, such as through symbols that remind the viewer of them. Her non-ontological but instead hauntological presence underpins the image even when the viewer cannot directly see her. This account of hauntology was developed by Mirzoeff, who observes that hauntological interplay between visibility and invisibility is a potent way of managing exclusion and generating diverse reception in different viewers:

The ghost is somewhere between the visible and the invisible, appearing clearly to some but not to others. Within the spectrum lies the spectral. In this digital age, the space warriors even want to militarize the hyperspectral. Some hear the ghost speak, for others it is silent. When visual culture tells stories, they are ghost stories.32

The hauntological presence is often symptomatic of the existence of the subaltern and her exclusion. Be it a colonial,33 racial34 or migratory spectre,35 the ghost—or the excluded—“has many names in many languages: diasporists, exiles, queers, migrants, gypsies, refugees, Tutsis, Palestinians.”36

Taking the theory of spectrality even further, Jo Frances Maddern has shown that some figures, such as migrants, have always been used as ghostly entities in what she calls spectropolitics, or, the politics of choosing who can and cannot speak.37 Drawing on Maddern’s theory, I argue that spectropolitics are not only used to exclude some subjects from participation but also from visibility. Spectropolitics involve the use of ghostly entities without showing them as visible subjects. Romeyn has convincingly shown how the presence of the other—be it Jewish, Muslim or migrant—is often construed as a threat. This threat fuels the logic of haunting, which is drawn upon to demonstrate the “excess of heterogeneity.”38 To terrify the viewer, the hauntological presence of individuals “excessive” to the current paradigm of a desirable society is strategically used with the purpose of inciting fear.39 As a ghost who does not feature in the frame, the migrant is not visible, but their presence is always on the horizon. Papalias has illustrated how the use of spectropolitics in relation to migrants is part of the nexus between biopolitics and necropolitics and the global power relations that dispossess subjects.40 Spectropolitics exclude the migrant from humanness by making them invisible and this dispossession legitimises the excessive response of the law. 41 Without the presence of the spectre, the often radical or unprecedented response of the law would be difficult to legitimise, if not impossible. The migrant’s invisibility as a human being and their presence as a threatening ghost disengages the viewer’s ethical response, while the haunting spectre generates a sense of fear. Thus, it is both the image and the lack of image that generate and manipulate power and incite, justify or exercise violence.42 In what follows, I will analyse the spectropolitics of portraying ghost-like figures of refugees and the exclusionary effects of such portrayals.

The ghostly illegals out of sight and outside the law

Illegality’s broadness results in a diversity of spectropolitical visualisations of the refugee. When the refugee is used as a haunting presence rather than as a real person with a face, story, family and a range of reasons for having migrated in a specific manner, their illegality can be depicted in a less sophisticated way.

The simplest way of capturing illegality is similar to the one we saw above in the war-time Canadian poster warning hoarders. Illegality can simply be represented by using symbolism directly associated with criminality and the workings of penal justice. Such depictions were used, for instance, in the UK in 2013 (prior to the Brexit vote), where the Home Affairs released the so-called Go-Home vans (fig. 2) to target migrants (mainly refugees) it considered illegal.43 The vans released during this campaign featured an image of handcuffs and an appeal to those so-called illegal people to turn themselves in and receive assistance with voluntary return. This image of handcuffs was deployed as a metonym for justice. in this depiction, however, the alleged illegal is not captured. Without showing the allegedly illegal subjects, this depiction relies upon the idea of the illegal; it implies that migrant illegality is a monster within, hiding and lurking “amongst us.”44 The intended emotive response is relatively straightforward—if genuine, migrants should be honest enough to either be in the territory legally or turn themselves in. If, however, migrants hide from authorities, they’re not only bogus, they are also illegal—in a criminal law understanding of the word—and can, therefore, be legitimately targeted with criminal law methods such as deprivation of liberty. Due to the invisibility of this monstrous spectre, the message to the wider community is as follows: all migrants have the potential to be illegal. By conflating the image of the handcuffs with words such as “go home” and “106 arrests last week in your area,” the shadow of an illegal ghost was cast upon all migrants. Since the migrant themselves remained invisible, their migrant status remained suspicious unless proven legal to the remaining population. The UK van campaign represents another straightforward method of using metonyms of justice in connection with invisibility to illustrate potential illegality of some migrants without depicting any migrants at all. Such use of symbols typically associated with criminality powerfully amplifies the need to use crimmigration methods to target those potentially hiding from the law.

While the British example is another relatively straight forward fusion of the ephemeral nature of illegality and the ghostly reliance of visual absence, some images take spectropolitics a lot further and use invisibility in a far more sophisticated manner. In 2014, the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection issued a graphic novel accompanied by the NO WAY poster and video campaign (fig. 3). The campaign was aimed at supporting the Operation Sovereign Borders, a maritime undertaking aimed at stopping refugee boats from arriving in Australian territorial waters and returning them to offshore detention centres on Manus Island and Nauru.45

In contrast to the simple resorting to the use of the shadow of the law in the British campaign, the NO WAY campaign is a form of a sophisticated mastery of spectropolitics which carefully balances the elements of visibility and invisibility. To justify the goal of turning back the boats—a policy overseen by current Australian PM Scott Morrison and later Minister for Immigration Peter Dutton—the pictorial mode of the NO WAY posters removes the refugee from the frame and focuses on the image of the boat. The image of the boat is singled out for an affective significance and symbolises the missing ghost—an illegal asylum seeker who can violently emerge on the horizon. For a long time, Australian political discourse had focused on the arrival by boat as a synonym for an arrival mired in deception, stealth, crime46 and illegal jumping of the non-existing refugee queue.47 Beginning from the Howard era, boat arrivals have gradually become a subject of multiple discussions leading to continuing changes in the law. From “irregular arrivals” included in the Migration Act 1958,48 those arriving by boat slowly became “illegal arrivals,”49 regardless of the fact that the Refugee Convention does not ban any form of arrival. The symbol of a boat used in political discussions has singled out a particular group of migrants and permanently affixed their mode of arrival to illegality. The existence of the fixed symbol of the boat effaced the unique experiences of those on board and connected them irrevocably with criminality. Persecution and meeting the protection criteria have been erased from political and legal discourse and replaced with discourse of delegalisation of boat arrivals. The refugees onboard boats arriving to Australian territorial waters became illegal by default, regardless of whether they met the international law criteria set out in the Refugee Convention.

Rather than using a simple reference to the criminal legal system, illegality and the ghostly invisible refugee were captured in the NO WAY poster by using the boat as proxy. The image not only reminded the viewer about the affective association between the boat and the construed illegality, but also amplified the fear of the ghosts on the horizon: the so-called boat arrivals. What makes amplifying an already existing fear possible is the invisibility of a refugee in the NO WAY campaign and their hauntological presence. The viewer seeing the NO WAY poster faces an open ocean with a small boat struggling in the violent waves in the hostile body of water. Due to the scale of the image the viewer cannot see any refugees in the picture but is, instead, invited to focus on the symbolic image signifying illegality: the boat, and a type of boat which since the Vietnamese refugees of the 1970s, has been racialised as Asian. It is little surprise that the viewers encountering a boat in the middle of a large frame accompanied by the words “NO WAY; YOU WILL NOT MAKE AUSTRALIA HOME” responded by emotionally identifying refugees with the powerfully affixed illegality of the boat. 50 The gaze point—the place from which the gaze is cast, is from the shore, which makes it clear that the message not is directed to the people on board. The posters were distributed overseas, ostensibly so as to discourage refugees taking this path to Australia, but they were widely seen in Australia where their effect served domestic politics. Here, the viewers equated to Australians watching the fate of the haunting boat from the safe distance of the Australian shoreline. In Poon’s words:

The real becomes abstract and the abstract becomes real in a substitution that completely removes the asylum seeker bodies from frame, overwriting them for the only body who is permitted at and who rules over the maritime border space—the sovereign.51

Poon further observes that law performs a metaphorical (or perhaps more accurately metonymical) trick by using the image of a boat as a substitute for asylum seeker.52 The spectropolitics become complete in the erasure of the persons onboard. This erasure creates the fear of the invisible ghostly migrant and leads to the viewer’s inability to truly imagine persons onboard as people. Manderson reminds us in the context of quite another, but equally potent image of a boat, that what follows is impossibility of picturing that the people on board “have families and communities that cherish their bodies and their memories.”53

When we look at the NO WAY campaign, we quickly realise that the invisibility of refugees and their hauntological presence fuel the threat of an illegal arrival. A viewer seeing the boat from the perspective of an Australian shore can easily justify the intervention of the criminal justice methods in approaching such illegals. After all, like ghosts these illegals can materialise fearlessly among the distant roaring waves of the horizon. The viewer confronted with such a broad frame haunted by the presence of the illegals on the distant horizon is capable of justifying and legitimising what would be hard to accept, should they look at the suffering faces of people instead.54 Looking at the boat presented through a frame conceived by the government, the viewer can easily legitimise exclusion of those onboard from the normal workings of the law.55 When confronted with the apparition of the boat and the ghostly invisible entities onboard, the viewer is unlikely to ask whether our domestic policy is illegal and contravening international law. Instead, the spectropolitics achieve their goal; fuelled by the fear of the invisible subject who is coming from the broad frame of the horizon, the viewer is likely to ask how the illegals can be prevented. The refugee, on the other hand, may not be able to recognise their own story in the empty image of the boat, which for them, signifies merely a vehicle of escape devoid of the association with illegality of any kind.

Spectropolitics are a powerful form of visual discourse that can remove subjects from the realm of the normal workings of the law. By using representational invisibility, spectropolitics reinforce administrative invisibility. Since 2013, refugees detained in offshore detention processing centres on Manus Island and Nauru as a result of the Operation Sovereign Borders and the so-called Pacific Solution have been stuck in the legal limbo,56 unable to be assessed and unable to leave to countries like New Zealand that have offered to welcome them.57 While the centres in Papua New Guinea have been found to be illegal by the domestic Constitutional Court in the host country,58 the removal of Australian personnel from the centres and opening their gates have not resulted in any legal progress for the majority of refugees detained there.59 Spectropolitics, by removing the refugee from the picture and replacing her with a ghost, have performed the ultimate trick of creating the Agambenian homo sacer:60 the subject so far outside the law that their existence is no longer ghostly in the image only, but also within and between the legal systems.61 Invisible in domestic migration laws in the places where they are detained, not allowed to be recognised by the places willing to host them due to Australian control of their status, and barred from accessing legal processes allowing for their recognition in Australia where their only legal status is that of an illegal, the offshore detention centre detainees captured at sea during Operation Sovereign Borders are the ultimate ghosts paying the price of the spectropolitical play with invisibility.

Conclusion

The interplay of visibility and invisibility in representations of migrants controls the narrative surrounding their legal status. Spectropolitical manipulation of the field of appearance is capable of fusing invisibility and illegality together allowing for masterful manipulation of how the migrant is seen in their absence. Their hauntological presence and creation of a threatening apparition of the illegal migrant/ refugee reflects the discourse of, on the one hand, genuine, hopeless and deprived refugees and, on the other, autonomous but illegal, bogus migrants harbouring illegal intentions. When spectropolitics fuse illegality and invisibility using the migrant/refugee as a threatening ghost, the control of their legal status becomes absolute. They become not only a ghost on the horizon of an image but also a legal ghost that the law needs to expel and protect borders from. As an illegal ghost they become the subject of crimmigration and can be effectively expelled from the legal system and deprived of any viable legal status. They become a ghost not only in the picture but also in access to legal remedies as well. Spectropolitical play with invisibility is a sinister form of manipulating the aesthetic field of appearance. It removes the migrant/refugee from the picture precisely in order to disable the possibility of the viewers to stand face to face with them as a person who is not unlike them. Spectropolitics fear such an encounter, because it risks allowing the viewers to lose the sense of purpose of many repressive migration laws. If viewers encountered migrants as people instead of threatening ghosts, they could perhaps no longer make sense of the cruelty of the current migration regimes.

-

Dominic McIver Lopes, “Out of sight, out of mind,” in Imagination, Philosophy and the Arts, eds. Matthew Kieran Dominic McIver Lopes (Routledge, 2003), 215–232.; Robyn Seglem and Shelbie Witte, “You Gotta See it to Believe it: Teaching Visual Literacy in the English Classroom,” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 53, no. 3 (2009): 216–226. ↩

-

More on processes of creating illegality in migration law see: Dauvergne, Catherine, Making People Illegal: What Globalization Means for Migration and Law, (Cambridge University Press, 2008). ↩

-

Sarah Whyte, “New Asylum Seeker Campaign ‘Distasteful’ and ‘Embarrassing’” The Sydney Morning Herald (website), February 12, 2014, accessed September 16, 2020, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/new-asylum-seeker-campaign-distasteful-and-embarrassing-20140212-32h04.html ↩

-

While visual campaigns have been previously sought to attract migrants, the figures of the invisible migrant can be placed in the context of current trends in migration law and their correlation with visual figures used by media and authorities, for more see: Dorota Anna Gozdecka, Visual Power, Representation and Migration Law (Edinburgh University Press, forthcoming 2021). ↩

-

Seth M. Holmes and Heide Castañeda, “Representing the ‘European Refugee Crisis’ in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death,” American Ethnologist 43, no. 1 (2016): 12–24. ↩

-

See: Katja Franko, The Crimmigrant Other: Migration and Penal Power (Oxon: Routledge, 2019); Brouwer Jelmer, Maartje van der Woude and Joanne Van der Leun, “Framing Migration and the Process of Crimmigration: A Systematic Analysis of the Media Representation of Unauthorized Immigrants in the Netherlands,” in European Journal of Criminology 14, no. 1 (2017): 100–119. ↩

-

Jefferey Andrew Weinstock, “Invisible Monsters: Vision, Horror, and Contemporary Culture,” in The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, eds. Asa Simon Mittman and Peter J. Dendle, (Burlington: Ashgate 2017), 275–289. ↩

-

Jo Frances Maddern, “Spectres of Migration and the Ghosts of Ellis Island,” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 3 (2008): 378. ↩

-

Gregg Barak, “Crime, Criminology and Human Rights: Towards an Understanding of State Criminality,” The Journal of Human Justice 2, no. 1 (1990): 11–28. ↩

-

Code of Public Local Laws of Baltimore City, para 24.1. ↩

-

State Religious Affairs Bureau Order (No. 5), Measures on the Management of the Reincarnation of Living Buddhas, Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. ↩

-

Jacques Derrida, “Force of Law: The ‘Mystical Foundation of Authority’,” in Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice, eds. Drucilla Cornell, Michael Rosenfield and David G. Carlson (New York: Routledge 1992), 3–67. ↩

-

Stephan Scheel and Vicki Squire, “Forced Migrants as Illegal Migrants,” in The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, eds. Elena Fiddian-Quasmiyeh et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2014), 188–99. For the contradictions in the earlier depictions of migrants and the tension between being welcome and being illegal one can look at posters and discourse from the time of White Australia Policy. See: Justine Greenwood, “The Migrant Follows the Tourist: Australian Immigration Publicity After the Second World War,” History Australia 11, no. 3 (2014): 74–96. ↩

-

Scheel and Squire, “Forced Migrants as Illegal Migrants,” 188–199. ↩

-

Julie A. Dowling and Jonathan Xavier Inda, eds. Governing Immigration Through Crime: A Reader, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013); Cecilia Menjívar and Daniel Kanstroom, eds. Constructing Immigrant ‘Illegality’: Critiques, Experiences, and Responses, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013). ↩

-

Catherine Dauvergne, Making People Illegal: What Globalization Means for Migration and Law, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Godfried Engbersen and Joanne Van der Leun, “The social Construction of Illegality and Criminality,” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 9, no. 1 (2001): 51–70. ↩

-

Scheel and Squire, “Forced Migrants as Illegal Migrants,” 188–199. ↩

-

Graeme Hugo, “From Compassion to Compliance? Trends in Refugee and Humanitarian Migration in Australia,” GeoJournal 56, no. 1 (2002), 27–37. ↩

-

Juliet Stumpf, “The Crimmigration Crisis: Immigrants, Crime, and Sovereign Power,” American University Law Review, 56 (2006): 367. ↩

-

Cecilia Menjívar Andrea Gómez Cervantes, and Daniel Alvord, “The Expansion of ‘Crimmigration,’ Mass Detention, and Deportation,” Sociology Compass 12, no. 4 (2018): 1–2. ↩

-

Menjívar, Cervantes, and Alvord, 380. ↩

-

Menjívar, Cervantes, and Alvord, 419. ↩

-

Simon Goodman and Susan A. Speer, “Category Use in the Construction of Asylum Seekers,” Critical Discourse Studies 4, no. 2 (2007): 165–185. ↩

-

Stumpf, “The Crimmigration Crisis,” 395. ↩

-

Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International (New York and London: Routledge, 2012). ↩

-

Robert Zacharias, “‘And Yet’: Derrida on Benjamin’s Divine Violence,” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature (2007): 103–116. ↩

-

Derrida, Specters of Marx, 48. ↩

-

Charles Garoian, “The Spectre of Visual Culture and the Hauntology of Collage,” in Spectacle Pedagogy: Art, Politics, and Visual Culture, eds. Charles Garoian and Yvonne Gaudelius (New York: State University of New York Press 2008), 114. ↩

-

Garoian, 116. ↩

-

Julian Wolfreys, Occasional Deconstructions (New York: State University of New York Press, 2004). ↩

-

Garoian, 116. ↩

-

Nicholas Mirzoeff, “Ghostwriting: Working out Visual Culture,” Journal of Visual Culture 1, no. 2 (2002): 239. ↩

-

Emilie Cameron, “Cultural Geographies Essay: Indigenous Spectrality and the Politics of Postcolonial Ghost Stories,” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 3 (2008): 383–393. ↩

-

Viviane Saleh-Hanna, “Black Feminist Hauntology. Rememory the Ghosts of Abolition?,” Champ Pénal/Penal Field 12 (2015), accessed 16 September 2020, https://doi.org/10.4000/champpenal.9168. ↩

-

Penelope Papailias, “(Un) Seeing Dead Refugee Bodies: Mourning Memes, Spectropolitics, and the Haunting of Europe,” Media, Culture & Society 41, no. 8 (2019): 1048–1068. ↩

-

Mirzoeff, “Ghostwriting,” 239. ↩

-

Maddern, “Spectres of Migration,” 378. ↩

-

Esther Romeyn, “Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia: Spectropolitics and Immigration,” Theory, Culture & Society 31, no. 6 (2014): 89. ↩

-

Weinstock, “Invisible Monsters,” 275–276. ↩

-

Papailias, “(Un) seeing,” 1053. ↩

-

Papailias, 1056. ↩

-

Jean-Luc Nancy, The Ground of the Image (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 21–22. ↩

-

Hannah Jones, Yasmin Gunaratnam, Gargi Bhattacharyya, and William Davies, Go Home?: The Politics of Immigration Controversies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017). ↩

-

Weinstock, “Invisible Monsters,” 284–286. ↩

-

Patrick van Berlo, “Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders: Discourse, Power, and Policy From A Crimmigration Perspective,” Refugee Survey Quarterly 34, no. 4 (2015): 75–104. ↩

-

Fiona H. McKay, Samantha L. Thomas, and R. Warwick Blood, “‘Any One of These Boat People Could be a Terrorist for All We Know!’ Media representations and public perceptions of ‘boat people’ arrivals in Australia,” Journalism 12, no. 5 (2011): 607–626. ↩

-

Katharine Gelber, “A Fair Queue? Australian Public Discourse on Refugees and Immigration,” Journal of Australian Studies 27, no. 77 (2003): 23–30. ↩

-

Elizabeth Rowe and Erin O’Brien, “Constructions of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Australian Political Discourse,” in Crime Justice and Social Democracy: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference 1, Queensland University of Technology, 2013, 173–181. ↩

-

Elizabeth Rowe and Erin O’Brien, “‘Genuine’ Refugees or Illegitimate ‘Boat People’: Political Constructions of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the Malaysia Deal Debate,” Australian Journal of Social Issues 49, no. 2 (2014): 171–193. ↩

-

Justine Poon, “How a Body Becomes a Boat: The Asylum Seeker in Law and Images,” Law & Literature 30, no. 1 (2018): 105–121. ↩

-

Poon, 114. ↩

-

Poon, 114. ↩

-

Desmond Manderson, “Bodies in the Water: On Reading Images More Sensibly,” Law & Literature 27, no. 2 (2015): 286. ↩

-

Rebecca B. Galemba, “Illegality and Invisibility at Margins and Borders.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review 36, no. 2 (2013): 274–285. ↩

-

Poon, “How a Body Becomes a Boat,” 115. ↩

-

Stewart Motha, Archiving Sovereignty: Law, History, Violence (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2018), 53–54. ↩

-

Binoy Kampmark, “Undermining NZ: Dutton’s Refugee Ploy,” Eureka Street 27, no. 23 (2017): 58. ↩

-

Azadeh Dastyari and Maria O’Sullivan, “Not for Export: The Failure of Australia’s Extraterritorial Processing Regime in Papua New Guinea and the Decision of the PNG Supreme Court in Namah (2016),” Monash University Law Rev, 42 (2016): 308. ↩

-

Maria Giannacopoulos and Claire Loughnan, “‘Closure’ at Manus Island and Carceral Expansion in the Open Air Prison,” Globalizations (2019): 1–18. ↩

-

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998). ↩

-

Michael Grewcock, “‘Our Lives is in Danger’: Manus Island and the End of Asylum,” Race & Class 59, no. 2 (2017): 70–89; Sara Dehm, “Outsourcing, Responsibility and Refugee Claim-Making in Australia’s Offshore Detention Regime,” Asylum for Sale: Profit and Protest in the Migration Industry SSRN UTS (website), accessed 16 September 2020, ↩

Dorota Anna Gozdecka is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Helsinki.

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

- Barak, Gregg. “Crime, Criminology and Human Rights: Towards an Understanding of State Criminality.” The Journal of Human Justice 2, no. 1 (1990): 11–28.

- Brouwer, Jelmer, Maartje van der Woude and Joanne Van der Leun. “Framing Migration and the Process of Crimmigration: A Systematic Analysis of the Media Representation of Unauthorized Immigrants in the Netherlands.” European Journal of Criminology 14, no. 1 (2017): 100–119.

- Cameron, Emilie. “Cultural Geographies Essay: Indigenous Spectrality and the Politics of Postcolonial Ghost Stories.” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 3 (2008): 383–393.

- Dastyari, Azadeh, and Maria O’Sullivan. “Not for Export: The Failure of Australia’s Extraterritorial Processing Regime in Papua New Guinea and the Decision of the PNG Supreme Court in Namah (2016).” Monash University Law Revue 42 (2016): 308.

- Dauvergne, Catherine. Making People Illegal: What Globalization Means for Migration and Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Dehm, Sara. “Outsourcing, Responsibility and Refugee Claim-Making in Australia’s Offshore Detention Regime.” Asylum for Sale: Profit and Protest in the Migration Industry. SSRN UTS (website), accessed 16 September 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3392128

- Derrida, Jacques. “Force of Law: The ‘Mystical Foundation of Authority’.” In Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice, edited by Drucilla Cornell, Michael Rosenfield and David G. Carlson, 3–67. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. New York and London: Routledge, 2012.

- Dowling, Julie A., and Jonathan Xavier Inda, eds. Governing Immigration Through Crime: A Reader. Standford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

- Engbersen, Godfried, and Joanne Van der Leun. “The Social Construction of Illegality and Criminality.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 9, no. 1 (2001): 51–70.

- Franko, Katja. The Crimmigrant Other: Migration and Penal Power. Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

- Garoian, Charles. “The Spectre of Visual Culture and the Hauntology of Collage,” In Spectacle Pedagogy: Art, Politics, and Visual Culture, edited by Charles Garoian and Yvonne Gaudelius, 99–118. New York: State University of New York Press, 2008.

- Gelber, Katharine. “A Fair Queue? Australian Public Discourse on Refugees and Immigration.” Journal of Australian Studies 27, no. 77 (2003): 23–30.

- Giannacopoulos, Maria, and Claire Loughnan. “‘Closure’ at Manus Island and Carceral Expansion in the Open Air Prison.” Globalizations (2019): 1–18.

- Greenwood, Justine. “The Migrant Follows the Tourist: Australian Immigration Publicity After the Second World War.” History Australia 11, no. 3 (2014): 74–96.

- Grewcock, Michael. “‘Our Lives is in Danger’: Manus Island and the End of Asylum.” Race & Class 59, no. 2 (2017): 70–89.

- Holmes, Seth M., and Heide Castañeda. “Representing the ‘European Refugee Crisis’ in Germany and Beyond: Deservingness and Difference, Life and Death.” American Ethnologist 43, no. 1 (2016): 12–24.

- Hugo, Graeme. “From Compassion to Compliance? Trends in Refugee and Humanitarian Migration in Australia.” GeoJournal 56, no. 1 (2002): 27–37.

- Jones, Hannah, Yasmin Gunaratnam, Gargi Bhattacharyya, and William Davies. Go Home?: The Politics of Immigration Controversies. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017.

- Kampmark, Binoy. “Undermining NZ: Dutton’s Refugee Ploy.” Eureka Street 27, no. 23 (2017): 58.

- Lopes, Dominic McIver. “Out of Sight, Out of Mind.” In Imagination, Philosophy and the Arts, pp. 215–232. Routledge, 2003

- Maddern, Jo Frances. “Spectres of Migration and the Ghosts of Ellis Island.” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 3 (2008): 359–381, p. 378.

- McKay, Fiona H., Samantha L. Thomas, and R. Warwick Blood. “‘Any One of These Boat People Could be a Terrorist for all we Know!’Media Representations and Public Perceptions of ‘Boat People’Arrivals in Australia.” Journalism 12, no. 5 (2011): 607–626.

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Daniel Kanstroom, eds. Constructing Immigrant ‘Illegality’: Critiques, Experiences, and Responses. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Menjívar, Cecilia, Andrea Gómez Cervantes, and Daniel Alvord. “The Expansion of “Crimmigration,” Mass Detention, and Deportation.” Sociology Compass 12, no. 4 (2018): 1–15.

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas. “Ghostwriting: Working Out Visual Culture.” Journal of Visual Culture 1, no. 2 (2002): 239–254.

- Motha, Stewart. Archiving Sovereignty: Law, History, Violence. Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2018, 53–54.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. The Ground of the Image. No. 51. USA: Fordham University Press, 2005, 21–22.

- Papailias, Penelope. “(Un) Seeing Dead Refugee Bodies: Mourning Memes, Spectropolitics, and the Haunting of Europe.” Media, Culture & Society 41, no. 8 (2019): 1048–1068.

- Poon, Justine. “How a Body Becomes a Boat: The Asylum Seeker in Law and Images.” Law & Literature 30, no. 1 (2018): 105–121.

- Romeyn, Esther. “Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia: Spectropolitics and Immigration.” Theory, Culture & Society 31, no. 6 (2014): 77–101.

- Rowe, Elizabeth, and Erin O’Brien. “Constructions of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Australian Political Discourse.” Crime Justice and Social Democracy: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference 1, 173–181.

- Saleh-Hanna, Viviane. “Black Feminist Hauntology. Rememory the Ghosts of Abolition?.” Champ Pénal/Penal Field 12 (2015). https://doi.org/10.4000/champpenal.9168.

- Scheel, Stephan, and Vicki Squire. “Forced Migrants as Illegal Migrants.” The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies (2014): 188–99.

- Seglem, Robyn, and Shelbie Witte. “You Gotta See it to Believe it: Teaching Visual Literacy in the English Classroom.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 53, no. 3 (2009): 216–226.

- Stumpf, Juliet. “The Crimmigration Crisis: Immigrants, Crime, and Sovereign Power.” American University Law Review, 56 (2006): 367.

- van Berlo, Patrick. “Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders: Discourse, Power, and Policy from a Crimmigration Perspective.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 34, no. 4 (2015): 75–104.

- Whyte, Sarah. “New Asylum Seeker Campaign ‘Distasteful’ and ‘Embarrassing’.” The Sydney Morning Herald (website), February 14, 2014, accessed 16 September 2020, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/new-asylum-seeker-campaign-distasteful-and-embarrassing-20140212-32h04.html

- Weinstock, Jefferey Andrew “Invisible Monsters: Vision, Horror, and Contemporary Culture”. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, edited by Asa Simon Mittman and Peter J. Dendle, 275–289. Burlington: Ashgate 2017 .

- Wolfreys, Julian. Occasional Deconstructions. New York: State University of New York Press, 2004.