The Dancer from the Dance Images and Imaginaries

O chestnut tree, great rooted blossomer, Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole? O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, How can we know the dancer from the dance?

— WB Yeats, “Among School Children”1

The reality of public space

Public space is not a metaphor. The long history of writing about it has always had a strikingly material dimension. This is obviously true when it comes to the ancient Greeks. For Socrates and then for Aristotle, the agora was not merely a metaphor for public life but the very moment and condition of its exercise. The same is true of the Roman forum. For Hannah Arendt, public space maintains this crucial connection to the embodied presence of public life. One might even say that the space itself summons and gathers a public as much as publics demand and institute spaces.2 When Arendt emphasises the political importance of “the space of appearance” she means a real space and the actual corporeal appearance of human beings in it.3

Politics … is a matter of people sharing a common world and a common space of appearance in which public concerns can emerge and be articulated from different perspectives. For politics to occur it is not enough to have a collection of private individuals voting separately and anonymously according to their private opinions. Rather these individuals must be able to see and talk to one another in public, to meet in a public space so that their differences as well as their commonalities can emerge and become the subject of democratic debate.4

Arendt’s work never loses its specifity, its almost literal evocation of the Greek marketplace or assembly—in short, her geographical and aesthetic imagination.

Undoubtedly, in the work of Jürgen Habermas public space becomes a public “sphere” and, in the process, public discourse is abstracted.5 The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere traces the rise and decline of “a category of bourgeois society” through an analysis anchored in philosophy and political economy.6 But it is striking how closely the first part of the book cleaves to the fundamental role played, in the explosion of media, discourse and intellectual life, by specific urban European geographies such as the salon and the coffee house. In the words of perhaps the earliest extant description we have, from sixteenth century Istanbul—

They look’d upon [coffee houses] as very proper to make acquaintances in, as well as to refresh and entertain themselves … Young people near the end of their publick Studies: such as were ready to enter upon publick Posts: Cadhis [magistrates] out of place, … the Muderis, or Professors of Law, and other Sciences; and, in fine, Persons of all Ranks flocked to them.7

For Habermas, public spaces were physically necessary to the development of the “public sphere.”8 There is no doubt that in his later work the model of discursive rationality is sublimated from its material roots, but they remain, as he says, both the “genesis” and the “basic blueprint” of the fundamental institutions of modern liberal democratic life.9

The language of metaphor hardly does justice to the connection between embodied space and political life. Neither does the notion of a metonym or synecdoche seem adequate when attempting to establish a relationship which is causal, constitutive, deeply rooted in people’s experience and agency. We would be better to follow Cornelius Castoriadis in insisting on the role of “the imaginary” in instituting social structures.10 The imaginary, in his influential telling, is to be distinguished from standard definitions of ideology through the role played by images, scenes, symbols and myths, and by the imaginary’s connection not to ideas but to human embodiment.11 In this sense, it is not “real” forces, in a Marxist sense, that shape institutional structures, but “imaginary ones”—God, the nation, the market, or public space.

All the same, I would take my leave from Castoriadis in treating the imaginary simply as a set of floating signifiers or transcendental ideations. On the contrary, the images that institute social structures and sustain what passes as common sense in a particular community are never experienced as a set of abstractions or claims. They are imbibed in and through the warp and weft of everyday life,12 or “the massive background of an intersubjectively shared lifeworld.”13 This vital connection between an image, on the one hand, and an embodied and material experience, on the other hand,14 is what drives the commitment to a specific idea of public space that we find in writers as diverse as Arendt and Habermas. Again, in Walter Benjamin’s unfinished work on the Arcades Project,15 both the fantasy of the flâneur and his embodied experience of Paris street life begin to point us towards a specific politics of recognition, a specific transformation of public space and public life under conditions of modernity.16 In other words, the powerful relationship between image and a specific and embodied geography is mutually constitutive. Images of public space provide, then, the raw material of the imaginary, evidence for its historical form or development, and a window on lived experience. They have one foot in ideological make-believe and the other in everyday life, each producing and reproducing the other.

Picturing good government

Let us take an example. Not, this time, the representation of the agora in Raphael’s School of Athens. Nor even the gruesome representation of the criminal body as public space, the equation of medical and legal knowledge, in Gerard David’s The Flaying of Sisamnes.17 For the sake of insisting on this connection between images, bodies, and public spaces, let us consider instead Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s remarkable frescos in Siena’s main hall of governance in the Palazzo Pubblico: nothing less than the visual constitution of the Republic of Siena, completed in 1339.

The intricate Allegory of Good Government at the front of the hall is flanked by two vast representations of civic life, now called The Allegory and Effects of Bad Government and The Effects of Good Government. The political theory expounded in the Allegory has been subject to much analysis.18 But of more interest for present purposes is the detailed portrayal of public life in the Effects of Good Government (fig. 1). As John White argued in a highly influential essay on “pictorial space” way back in 1957, Lorenzetti’s masterpiece marks a breakthrough in the representation of public space in Western art, and a crucial milestone on the road towards the adoption of a systematic approach to perspective a century or more later. It is not just the multitude of details that build such a compelling picture of vibrant civic life. The sense of space itself has been enlarged and made realistic in a new way. “Full rein is given to the new sense of space apparent in the structure of the town. A panoramic vision of the countryside unfolds for the first time, dimishing into the distance with the continuity of natural space.”19 This sense of three-dimensional space, and public participation in it—trade, family life, pleasure and public discourse are to be found in every corner of the happy town—are not merely represented. They form the argument of the triptych as a whole: “good government” is not merely a moral obligation or spiritual virtue. It is valued precisely for its effects, principal amongst which are the flourishing public spaces which Lorenzetti depicts. The figure of Securitas stands guard over the city. Her purpose is not to safeguard the established order or to empty the public square. On the contrary, it is to protect and ensure their operation. On the facing wall, the effects of “bad government” are the opposite. Under the figure of Timor (fear), the city is surrendered to frenzied violence and division: shuttered windows, dilapidated buildings, and a city emptied of all life, save soldiers and brigands.

Public space itself, and not just the figures that fill it, are the star of the show. It is Lorenzetti’s sophisticated use of perspective that gives that space a three-dimensional effect that invites the viewer into it. Yet as White points out, Lorenzetti’s use of perspective is at first unsettling. The group of dancers in the middle of the fresco seem weirdly outsized. Figures recede not just as our eyes move into the background, but also from left to right. This is not linear perspective presented from the position of the viewer, as we have come to know it.20 Rather, the painting’s perspective is designed from a point of view inside the image, specifically from the point of view of the dancing group. The members of the dancing group are the central figures of the whole narrative. The fresco has been organised as it might be perceived from their point of view. They are larger than figures on the same plane, and everything recedes into the distance according to its distance from them; hence the strange fact that figures on the far right are much smaller than those on the far left, in a manner that could never, for example, be countenanced by the painters of the Italian Renaissance or the Dutch golden age.21 And so too the source of light in the image is not natural. It pours out from the dancers themselves, illuminating the right-hand side of those to their left and the left-hand side of those to their right.22 All the “effects of good government,” all the benefits of public life, the very light by which we see them—come from the dancers and the dance (fig. 2).

The meaning of the dancers has been hotly contested. The figures have often been called “maidens,” but this has been convincingly disproved by Quentin Skinner, who identifies them as young men performing the stately tripudium as a sign of dignified or ceremonial joy.23 There are nine of them (the tenth figure in the group is not a dancer; she is disciplining the dancers movements by singing and banging a tambourine: rhythm, we might hazard, is the law of the dance). The number nine is repeated throughout the frescoes with almost kabbalistic mysticism. Lorenzetti’s frescos are in the Sala dei Nove, the hall of the Nine, the elected body responsible for Siena’s executive and judicial government. Their responsibilities and their relationship to the people of Siena, to justice and to God, is expressed in the Allegory. But the “effects of good government” is not an allegory. Dancing becomes here a kind of affective pedagogy in public life: it demands personal touch, engagement and connection, but it also requires co-operation, harmony, and the transcendence of individual interest for the benefit of some greater and collective good. The dance is not a metaphor for the republican virtues but a social practice that instils them. The image of the dancers in Lorenzetti’s masterpiece helps constitute the imaginary of Republican Siena; but at the same time, the act of dancing itself affirms the reality of that imaginary. The picture connects the image of public space and public life—plenary, diverse, and embodied—to everyday life in a way that continually reinforces the links between them.

Nine is not just the sign of government, but the sign of art—the number of the muses, a reminder of the value of feeling and creativity in public life: of poetry, and music, tragedy and comedy, and of Terpsichore, the muse of the dance. In the corporeal and affective character he gives the Effects of Good Government, Lorenzetti entwines government and art, and embodies them both in a dance. Look at the movements the dances are making. The rulers and the ruled are weaving together a complex tapestry of public life. Light emanates from them, filling the wall, the hall, and the city. O body swayed to music, O brightening glance—civic life performed in public space becomes a model of the unification of free will and necessity. The effects of good government, it seems, fuse together pleasure and duty, until we cannot tell them apart.

Scenes from the neoliberal imaginary

If we turn now, with alarming abruptness, to the modern world, it is worth asking about what kinds of images of public space populate our own imaginary, or to put it another way, what sorts of images reflect and constitute contemporary visions of public space? For it is fair to say that neoliberalism loathes and distrusts public space. Neoliberal thought was always antipathetic to democracy, and indeed sought to shield market freedom, property rights, and economic management from its pernicious effects. Thinkers like Friedich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises thought that public discourse and democratic politics, left unchecked, would inevitably lean towards policies of redistribution, welfare, and social security—precisely inimical to the individual and market-based freedoms that they thought essential to a true liberalism.24 In a startlingly candid interview in defence of Pinochet’s Chile, Hayek frankly avowed that he would prefer a “liberal dictator” to a “democratic government lacking in liberalism.”25 Wendy Brown, following Michel Foucault, accuses neoliberal policies of weakening democratic institutions and narrowing public space around the world.26 By creating a hegemonic discourse of “neoliberal reason,” wherein all human and social interactions must be understood exclusively in terms of individual and economic goals, the basis of social and collective action is removed. The language of “society” and of public life becomes unthinkable.

The neoliberal imaginary has converted public life into private life, and public space into private space. It is right in front of our eyes. In a series of works, Richard Sennett has traced the demise of the city and its replacement by suburban existence. Public space in the modern city, he argues, has become something to be feared, not embraced, an “empty space, a space of abstract freedom but no enduring human connection.”27 Against this pessimistic reading, several scholars have developed a more pluralistic account, emphasizing the flexible and adaptive elements of urban living. Sharon Zukin defends the capacity of citizens to appropriate and repurpose spaces creatively, claiming for example that “the public regards the theme park as public space.”28 Good for them—but try and hold an anti-war demonstration in Disneyland and see how far it gets you. Such an approach profoundly underestimates the extent to which legal (and economic) frameworks constrain this civic dynamism. The classic example is the shopping mall.29 The shopping mall, as we know, has been the graveyard of main streets and public squares all over the world. But the mall gives only a simulcrum of public space. People’s behaviour and actions are vigorously regulated by the corporations that own them and the security guards that police them, with greater powers than actual police on actual streets. There are very real limits on the kinds of political and social activities that are tolerated including, most obviously, where they might interfere with the mall’s economic imperative.30 Shopping malls have replaced public spaces with their neoliberal doppelganger.

Consider another kind of familiar image—the brochure proposing or promoting a new apartment complex, museum, or institution. Invariably these designs provide an enticing mise-en-scène: open spaces, trees and plazas full of people. But with few exceptions there is something generic about these images. The images have a pallid palette and a high-gloss finish. Their computer-generated superficiality repels a deeper engagement. The people they show—strikingly white and middle class, at least on my limited sampling—are not in public space but move through it. At best they may pause and sip a coffee en route between appointments. In this it is quite different from the Parisian boulevard of the nineteenth century, where to see and be seen was the whole point. On the contrary, the plaza or the promenade in the twenty-first century is liminal not central. It is a means not an ends: a thoroughfare for pedestrians; a space that connects destinations, not a destination itself. As if complicit in laws against public assembly, there are rarely more than two or three people in a grouping. We are not to imagine a meeting or a protest or an assembly or a street march, still less a “riot,” which English law traditionally defined as a gathering of twelve or more.31 The activities that take place here are not social, let alone political. They are personal, corporate, or at best domestic. In representing public space in this fashion, images do their dual work, encouraging their reproduction by bodies in the world, and embedding an ideological understanding of space, belonging, and relationships as common sense.

A good example as to what is at stake is provided by a recent dispute involving the Sydney Opera House. Racing NSW wanted to advertise a million dollar horse race. It sought to “rent” the sails of the iconic building to project the horses” names, numbers, and colours onto it during a live stream of the barrier draw (fig. 3). Not surprisingly, Louise Herron, CEO of the Opera House, demurred. This created furor e divisio32 in various media outlets in Sydney. Alan Jones, the country’s most influential shock-jock, fulminated from his bully pulpit. Facing considerable pressure, the CEO agreed to screen the colours but not commercial text or company logos. But even that was not good enough. In a live interview with Herron which demonstrated the levels of animus and abuse for which Jones is well known, he shouted “We own the Opera House. Do you get that message? You don’t. You manage it.” Herron reminded Jones of the Opera House’s world heritage status. “It’s not a billboard,” she said. He replied: “Who said? You. Who the hell do you think … who do you think you are?”33

Yet Jones’ rant provoked a widespread backlash from members of the public. They angrily defended the CEO’s judgment. Jones was forced to apologise for his behaviour. On the night of the event, thousands of Australians gathered in front of the Opera House and shone the lights on their phones onto the sails. Feeble individually, their collective action effectively spoiled the effect of the projection and drove Racing NSW to radically curtail the event. The public reaction demonstrated the depth of feeling that a building like the Opera House can still inspire. For what was at play in the image of the Opera House were two opposed understandings of public space. For Jones, precisely because the Opera House was a public space, it must be for sale; commercial value was the only way that return on public investment could be measured and maximised. We own it, you manage it, he said. As Brown puts it, in the logic of neoliberal reason, “common good” and “non-economic value” are oxymorons. But for Herron and others, because the Opera House was a public space, it must not be for sale; its non-economic value as a public good had to be protected from commercial exploitation. Both sides thought that they were defending the public interest, but in contradictory ways.

This conflict generated intense passion on both sides. Aesthetic experience was, as it often is, a lightning rod for very different ways of understanding public life. Image, body, and space collided, and not just metaphorically or symbolically. Like Lorenzetti’s dancers, the public responded by putting their bodies (and, yes, their smartphones) on the line in a collective and co-ordinated action that transcended their individual capacity and, for a moment, brought them together as and for a res publica, a public thing. Thus were Hayek’s anxieties about anti-liberal and democratic social power confirmed.

Towards the destruction of the public sphere

Brown’s emphasis on the ideological power of the neoliberal imaginary is important, but it does not go far enough. The destruction of the public sphere is not a side effect but a deliberate aim of neoliberal politics. If the public square will not empty itself, strong government action is called for. In Australia, a neoliberal government has been steadily doing just that since it came to power in 2013. The government has established new offences of “advocating terrorism” and modified the definition of a terrorist organisation to include any organisation that “counsels, promotes, encourages or urges” or “praises” a terrorist act.34 Unsurprisingly, the “terrorist organisations” blacklisted by the government have been, with one exception, Muslim organisations. The ongoing threat of prosecution or proscription has undoubtedly chilled public activism by Muslims in Australia.35 But, of course, what is or is not terrorism as opposed to political struggle is a partisan judgment. Australia’s terrorism laws are certainly wide enough to have prohibited, for example, organisations that supported the African National Congress when it was outlawed in South Africa. They could certainly be used to prohibit organisations calling for a new intifada in the occupied territories. Meanwhile, expansion of the discourse of terrorism to encompass other forms of domestic political dissent is well underway. Queensland legislation aimed at breaking up “bikie gangs” made liberal use of the language of emergency and did not hesitate to describe their targets as domestic terrorists. Laws directed against environmental activists have already been passed in Queensland and proposed in Tasmania, after previous legislation was struck down by the High Court of Australia.36

The language of “eco-terrorism” is gaining currency, particularly in the hands and mouths of a government whose climate denial credentials are impeccable. A school climate strike seems a harmless enough use of public space. But the day is not far off when children and young people holding placards in support of Extinction Rebellion will be considered guilty of advocating, or praising, or encouraging terrorism. Admittedly, the legislative definition of terrorist acts does not extend to “advocacy, protest, dissent, or industrial action” where there is no intention “to create a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public.”37 But who will determine what constitutes a serious risk to the safety of a section of the public? At what point will the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) undertake “special intelligence operations”38 in the course of which the brothers and sisters of environmental activists might have “important” information, be detained without charge and coerced into providing intelligence to be used in secret trials in which the Minister determines whether “national security” is at risk, and a “fair trial” is not a consideration?39 Under what circumstances will environmental activists be convicted of terrorist acts or advocating terrorism? At which point young Australians can now be stripped of their citizenship and deported if the Minister for Home Affairs forms the view that they are opposed to “Australia’s interests, values, democratic beliefs, rights or liberties”?40This is what Jenny Hocking meant by the “criminalisation of politics.”41 A legal web is slowly strangling the public life of more and more people. The Espionage and Foreign Interference Act requires the registration of activists and human rights groups involved with international organisations and prevents donations from non-Australian citizens. Revised offences of “espionage” and “foreign interference” cover any conduct “on behalf of, or in collaboration with, a foreign principal”—not just a government but equally “foreign political organisations” and “public international organisations”—intended to “influence a political or governmental process” or “influence the exercise” of an “Australian democratic or political right or duty.”42 Such conduct must be “covert” or “deceptive” but this includes “any conduct that is hidden or secret, or lacking transparency,” for example “if a person takes steps to conceal their communications with the foreign principal.” 43 The consequences for public activism will be far-reaching. International campaigns and boycotts may become almost impossible.44 Even reporting information to the United Nations or Amnesty International, for example concerning the Australian government’s violation of its international obligations, might be illegal. Campaigns by Greenpeace or Sea Shepherd Conservation Society or Extinction Rebellion risk prosecution. Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull characterised the Act as directed at political interference by China and Russia, but its real effects will largely fall on environmentalists and human rights activists.

Neoliberal governance marginalises these concerns, reducing the capacity of civil society to make its voice felt, and turning critics into criminals or indeed terrorists. Legitimate public space is shrinking. In a similar vein, Prime Minister Scott Morrison recently sounded the possibility of using the government’s construction code to prevent consumers from engaging in “secondary boycotts” of Australian companies on environmental or ethical grounds.45 The neoliberal distinction between economic and political concerns insists that the Australian consumer, as homo economicus, cares about nothing but profit. At stake is the very idea of “neoliberal reason,” and the stunningly limited role the citizen is to be allowed in its operation.

Contamination and control

As I write this paragraph, we are all locked down: assemblies or gatherings banned, schools and universities closed, public events cancelled, infected persons dragged by violence and force to hospitals and detention centres. This might be a once in a lifetime event, but it is more likely that it’s the new normal. As global networks of information become more and more sophisticated, warnings, viruses, and lockdowns will only intensify from here. Knowledge and power, like one hand washing the other.46 It is not so much that there is no call for drastic measures, but how neatly the fear of public space advances a broader neoliberal agenda. In the short term, government funding to ease the pain that the coronavirus depression is causing, are to be welcomed. But one is sceptical that any attempt will be made to confront the long term effects of the pandemic. Who will bear the brunt of these effects? The usual suspects. Aboriginal people, the poor, homeless and disadvantaged, a vast new army of unemployed, students. How much support will the government give to the university sector whose business model has been comprehensively broken? It’s not the only possible outcome, but it is not unreasonable to imagine that the pandemic will, in the final analysis, turn out to be neoliberalism on speed.

The right-wing newspaper the Sunday Telegraph has a front page story headlined “Army Enters Virus Wars,” illustrated by a photo of two, presumably Australian but nonetheless recognisably Chinese, women in face masks. The language of fear and the rhetoric of war justify important public health measures. But they also legitimate a more generalised fear and anxiety, including the undoubtedly racist sub-text of this image. The traditional right has always found “law and order” a useful platform from which to launch anti-progressive and racist policies; the new right will find the “law and bio-security” platform equally fertile ground. As Rahm Emanuel, political fixer par excellence, said: “You never let a serious crisis go to waste. And what I mean by that it’s an opportunity to do things you think you could not do before.”47 It is increasingly apparent that the public health emergency of the COVID-19 epidemic is also a way of instituting more comprehensive controls over public space, sidestepping democratic controls over executive power, and ensuring that controversial economic projects can be pushed through as “essential services.” In Hungary the pandemic has served to further tighten State controls over democratic and social life. In the United States, the Keystone oil pipeline can finally be rushed through without the meddlesome activism of environmental protesters.48

This is the nature and disciplinary reach of contemporary bio-politics, in which human beings are increasingly imagined not as citizens with rights but as bodies to be herded.49 In such a world, public space is not the heart of the body politic, but a breeding ground for illicit contamination.50 The contrast with Lorenzetti’s image is profound. The Effects of Good Government celebrates a city at the height of its powers—open, optimistic, and confident. To the freedom of public space corresponds a free and constant intercourse with the surrounding countryside on which Siena’s prosperity depended. A scant nine years later, in 1348, the black death arrived, dramatically curtailing the city’s public and political freedoms, killing up to half the population, and dealing its economy and status a hammer blow from which it never recovered.51 Art too was transformed under the experience of the plague.52 Lorenzetti’s frescoes rhapsodise an ideal of public space and political life, caught at the very moment of its passing. Perhaps they are not so much the visual constitution of Siena as its memorial.

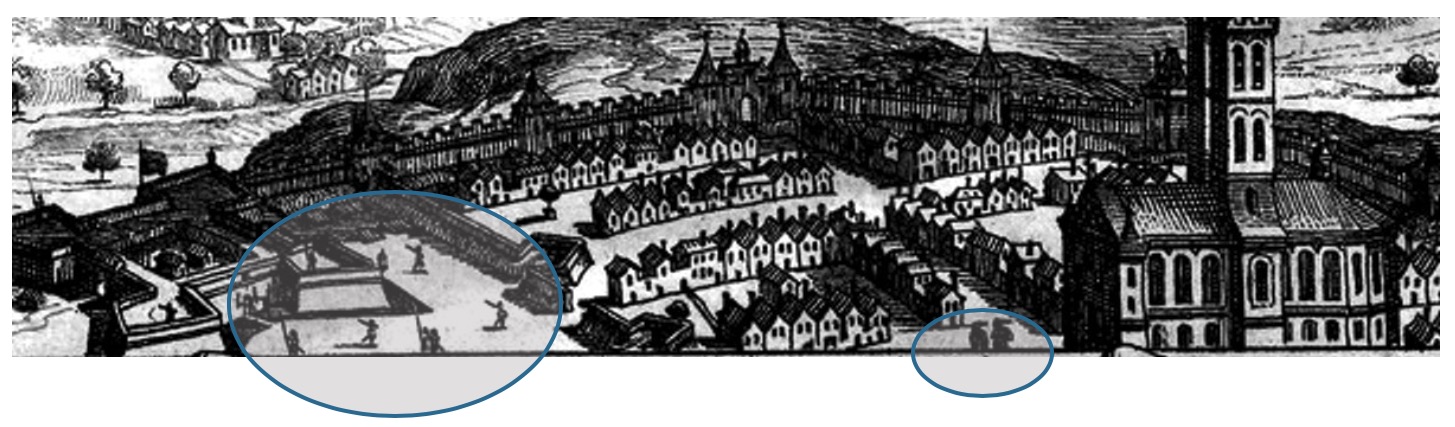

By the time Thomas Hobbes came to write Leviathan in 1651, London had been ravaged by the plague, on multiple occasions, for 300 years. The generally accepted figure is that it lead to the deaths of 20 percent of the population every twenty or thirty years. Indeed, it was to return one last time in 1665, killing over 100,000 people. No doubt Hobbes’ theory of sovereignty and violence owes more to the dreadful catastrophe of the Civil War, from which England was still reeling. But memories of the plague were not entirely absent, if you look closely enough. Indeed, questions of embodiment, health and disease in and of the state are Hobbes’ recurrent metaphor. The Frontispiece to the first edition (fig. 4) depicts the sovereign precisely as a body politic. In the shadow of this giant figure, an ordered town lies sheltering. Only soldiers and plague doctors patrol the empty city streets—waiting to stamp out the next outbreak, be it medical or political, disease or unrest.53 Where securitas ends and timor begins is hard to say. But this much is certain: dancing is strictly prohibited.

Emptying the public square

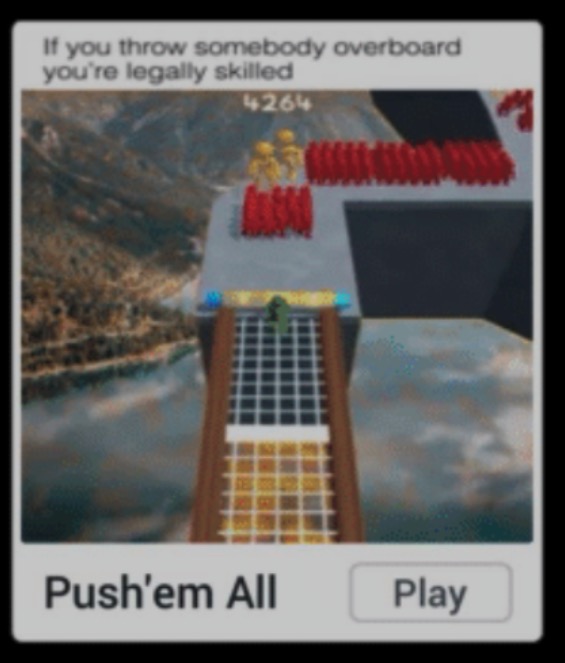

We don’t have to turn to history in order to appreciate the extent to which the reiminaging of public space has permeated our recreations and our imagination as much as our work and our everyday life. Push ‘em all (fig. 5) provides a telling instance. Many video games are now multi-million dollar spectaculars that cost as much as a blockbuster movie to produce. Push ‘em all is not one of them. It is cheaply made, of the sort that you can get free online and that make their pennies from the ads they force you to watch. It is owned by the game developer Voodoo, the number one publisher on App Store by downloads, which specialises in such low-end games, and has been accused of stealing or copying content from independent creators.54 Push ‘em all is currently one of their biggest sellers.55 It was downloaded six million times in late 2019, and was briefly ranked the fourth most popular free app across all categories.56 It features a single figure pushing a large log. There are masses of other figures in front of them, all the same colour and indistinguishable from one another. By pushing them with its log the player can clear the site of these contaminants, scattering them and sending them plunging over the edge of the play area to their doom.

Public gatherings in Hong Kong, Beijing, Brisbane: push ‘em all. Rab’a Square 2013; Tienanmen Square 1989; Tlatelolco 1968; Amritsar 1919. “Push them hard” adds the App Store encouragingly. It is hard not to see the game as a legitimation of authoritarian violence. This is what neoliberal governance looks like: the cleansing of the public space of dissent, of all populations, by violent police action. The game embodies some kind of fantasy of the perfect placid emptiness of public space and of the nihilistic satisfactions of the will to power. “Zone cleaned,” as the game intones in its electronically anodyne voice after you have completed a level. A zone not a space or a place with a history or function; it is an abstract administrative field. “Cleaned” implies an aesthetic and medical value—an act of public health—quite different from words like evacuated or emptied. The language is that of a computer game but it is equally the language of governance. The game encourages us to see the world this way, to accept its constraints and its violence, and to take pleasure in its cleanliness and discipline; to imagine ourselves as street cleaners committed to sweeping aside political detritus. The public, in public space, is a kind of dirt.

A video game seems eerily fitting. The result of the neoliberal ascendancy, says Brown, is the “desublimation of the will to power,”57 sending pulses of nihilism and destruction unchecked through a crippled and delegitimised public sphere. This desublimation turns political discourse itself into a game.58 The will to power manifests itself not only in the release of nihilistic and destructive energies but also in an unbridled sense of entitlement. Play, power, and right become indistinguishable.59 Some figures seem to be gathering together; some look like they’re minding their own business. Some hold up their hands in supplication. Some try and run away. Too bad. The game speaks clearly to the need to repress political dissent in the name of political order. But at the same time, and just as importantly, it illuminates the role of contemporary media as a mode of imaginary reproduction. These images that turn the assault on public space into a game both illustrate ideological assumptions and shape them. As Louis Marin put it, they “valorise” and “modalise” power—give it a legitimacy and put it to work in our lives.60

The game offers up this pearl of wisdom (fig. 6): “If you throw somebody overboard, you’re legally skilled.”61 At the risk of overthinking it, the word “overboard” is surely no accident. We are sending refugees or protesters to their death, whether off Lampadusa or Christmas Island.62 We should push ‘em all—away, away, driving them back into the sea. Even more, we should not just push them but “throw somebody,” in other words, actively expel human beings from our territory. In taking these actions, the game does not merely encourage us to enjoy our power. It insists that it is right to do so. The law is on our side. Violent acts by riot police or by border security do not simply demonstrate a technological mastery. They are a tribute to our “legal skill.”

These legal skills the Australian government is honing to perfection, in anticipation of the need to “push ‘em all” in the not too distant future. The government is setting in place legal structures that will enable it to win the neoliberal game. Welfare laws, terrorism laws and border security are vivid manifestations of its desublimated nihilism, and simultaneously the measures needed to smash any resistance to it. It is the perfect ideology, which we might define as the fusion of pleasure and duty. What in Lorenzetti looked like the harmonious coming together of co-operative and public action, in our modern era seems more like its willing surrender. The strength of ideology lies in its capacity to generate motivated action in accordance with its beliefs. But its danger lies in the inscription of blindness and conformity into the everyday lives of citizens. Dancer and dance, violence and game, we are both neoliberalism’s script and its embodiment.63 The task, in neoliberal art as in life, is zone cleaned. O body swayed to music, O brightening glance; our bodies shape to the task and embrace it as our duty and our pleasure.

If there is a glimmer of hope to be found in any of this, it is the apparent reliance on state and law to impose these terms. It suggests that neoliberal ideology is not adequate to maintain its economic and social power. Increasing force and the shrillness of political rhetoric suggest growing resistance.64 That public square won’t empty itself. I cannot help but think that the game, in real life or on the screen, would be more challenging—and far more interesting—if played from the other side of the log. What opportunities for resistance would present themselves? For collaboration? For transformation? This would be a much harder game to play. But it would be more rewarding too. When all is said and done, “push ‘em all” is a tedious and futile exercise. It’s not a dream, it’s a nightmare. Cleaning the zones just takes you deeper and deeper into a game you never win, level after level after level. It may yet be urgently necessary to reject these enticements, once and for all to prise apart the dancer from the dance.

-

WB Yeats, “Among School Children,” in Collected Poems, ed. Richard Finneran (New York: Scribner, 1996) #222. ↩

-

James Mensch, Embodiments: From the body to the body politic (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2009); Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). ↩

-

Philip Howell, “Public space and the public sphere: political theory and the historical geography of modernity,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11, no. 3 (1993): 303-322, 314. ↩

-

Maurizio d’Entrèves, The Political Philosophy of Hannah Arendt (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 146. ↩

-

See Seyla Benhabib, “Models of public space: Hannah Arendt, the liberal tradition and Jiirgen Habermas,” in Situating the Self: Gender, Community and Postmodernism in Contemporary Ethics, ed. Seyla Benhabib (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1992), 89–120. ↩

-

Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1963] (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991). ↩

-

Markman Ellis, Introduction to the Coffee-House. A discursive model, http://www.kahve–house.com/coffeebook.pdf, quoted in Desmond Manderson and Sarah Turner, “Coffee House: Habitus and Performance Among Law Students,” Law and Social Inquiry 31 (2006): 649–76, 650. See also Markman Ellis, The Coffee House: A Cultural History (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2004). ↩

-

Chris Philo, “Of Public Spheres & Coffee Houses” [2004] Department of Geography & Geomatics http://finbar.geog.gla.ac.uk/E_Laurier/cafesite/texts/cphilo016.pdf. ↩

-

Habermas, Structural Transformation, 32, and see chapters 3 and 4; Craig Calhoun, Habermas and the Public Sphere (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992). ↩

-

Cornelius Castoriadis, The Imaginary Institution of Society [1975] (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997). ↩

-

John Thompson, “Ideology and the Social Imaginary: An Appraisal of Castoriadis and Lefort,” Theory and Society 11, no. 5 (1985): 659–681; Leif Dahlberg, “Factoring Out Justice. Imaginaries of Community, Law, and the Political in Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Niccolò Machiavelli,” Lychnos (2013): 35–73, 64. ↩

-

This is precisely the argument made by Claude Lefort: Thompson, “Ideology and the Social Imaginary,” 665–7. ↩

-

Jürgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (London: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 322. ↩

-

I think this is part of what Chiara Bottici is attempting to express in Imaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the Imaginary (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014) although the argument here has a different emphasis. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999). ↩

-

David Frisby, “The Flâneur in Social Theory,” in The Flaneur (RLE Social Theory) (London: Routledge, 2014), 81–110. ↩

-

Ronnie Lippens, “Gerard David’s Cambyses [1498] and Early Modern Governance: The Butchery of Law and the Tactile Geology of Skin,” Law and Humanities 1 (2009): 1–24. ↩

-

Nicolai Rubinstein, “Political Ideas in Sienese Art: The Frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Taddeo di Bartolo in the Palazzo Pubblico,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 21 (1958): 179–207; Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher,” Proceedings of the British Academy 72 (1986); Quentin Skinner, “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes: Two Old Questions, Two New Answers,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 62 (1999): 1–28. ↩

-

John White, The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space (London: Faber & Faber, 1957). ↩

-

Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form (New York: Zone Books, 1991); Margaret Iversen, “The Discourse of Perspective in the Twentieth Century: Panofsky, Damisch, Lacan,” Oxford Art Journal 28, no. 2 (2005): 191–202; Hubert Damisch, L’origine de la Perspective (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994). ↩

-

On the distinctive use of perspective by the Dutch masters, see Svetlana Alpers, The Art of Describing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983). ↩

-

C. Jean Campbell, “The City’s New Clothes: Ambrogio Lorenzetti and the Poetics of Peace,” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 2 (2001): 240–258; White, Birth and Rebirth. ↩

-

Skinner, “Two Old Questions,” 16–19, 26. ↩

-

See Jessica Whyte, The Morals of the Market (London: Verso, 2019); Wendy Brown, Undoing the demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015); Philip Mirowski, “Defining Neoliberalism,” in Philip Mirowski and Dieter Pluhwe, eds., The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015): 417–450, 446. ↩

-

Quoted in Philip Mirowski and Dieter Pluhwe, eds., The Road from Mont Pelerin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 328; Friedrich Hayek, Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, 161 in Mirowski, Defining Neoliberalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967), 446. See also Loïc Wacquant, “Crafting the Neoliberal State,” Sociological Forum 25 (2010): 197–220, 202. ↩

-

Brown, Undoing the Demos; Wendy Brown, “Neoliberalism’s Scorpion Tail,” in Étienne Balibar et al, Mutant Neoliberalism: Market Rule and Political Rupture (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 39–60; Wendy Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). See Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2008); Stephen Sawyer and Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins, Foucault, Neoliberalism and Beyond (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2019). ↩

-

Richard Sennett, Flesh and stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization (New York: WW Norton & Company, 1996); see Peter Goheen, “Public Space and the Geography of the Modern City,” Progress in Human Geography 22, no. 4 (1998): 479-496, 482–3. ↩

-

Sharon Zukin, Cultures of Cities (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), in Goohen, “Public Space and the Geography of the Modern City,” 486; Philip Ethington, The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). ↩

-

Denis Brion, “The Shopping Mall: Signs of Power,” in Law and Semiotics, ed. Roberta Kevelsen (Boston: Springer, 1987), 65–108; Nancy Cohen, America’s Marketplace: The History of Shopping centers (Lyme, CT: Greenwich Publishing Group, 2002); Mona Abaza, “Shopping Malls, Consumer Culture and the Reshaping of Public Space in Egypt,” Theory, Culture & Society 18, no. 5 (2001): 97–122; Malcolm Voyce, “Shopping Malls in Australia: The end of public space and the rise of “consumerist citizenship”?” Journal of sociology 42, no. 3 (2006): 269–286. ↩

-

Mark Button, “Private Security and the Policing of Quasi-Public Space,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 31, no. 3 (2003): 227–237. ↩

-

Riot Act 1714 UK 1 Geo 1, c 5, s 2. ↩

-

The reference is to the labels attached to tyrannical government in Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Allegory of Bad Government. ↩

-

Transcript of interview in Jacob Saulwick and Rachel Clun, “Alan Jones calls on Berejiklian to sack Opera House boss over racing dispute,” Sydney Morning Herald, October 5, 2018, https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/alan-jones-calls-on-berejiklian-to-sack-opera-house-boss-over-racing-dispute-20181005-p507x8.html. ↩

-

Counter‑Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Foreign Fighters) Act 2014 (Commonwealth of Australia), ss 60–67, amending Criminal Code Act 1995 (Commonwealth of Australia), ss 80.2C, 102.1 (1A), 102.1AA. ↩

-

Tufyal Choudhury and Helen Fenwick, “The Impact of Counter-Terrorism Measures on Muslim Communities,” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 25 (2011): 151–81. ↩

-

Summary Offences and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2019 (Queensland), ss2–6, amending Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000 (Queensland), ss 30 and 32 and inserting s 53AA; Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Amendment Bill 2019 (Tasmania); Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Act 2014 (Tas); Brown v Tasmania, [2017] HCA 43 (High Court of Australia). ↩

-

Criminal Code 1995 (Commonwealth of Australia), s 100.1(3). ↩

-

Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (Commonwealth of Australia) ss 4, 35K, 35P, s 34ZS(2); National Security Legislation Amendment Act (No. 1) 2014 (Commonwealth of Australia); George Williams, “The Legal Assault on Australian Democracy,” Queensland University of Technology Law Review (2016) 16: 19, 28–29; Kieran Hardy and George Williams, “Special Intelligence Operations and Freedom of the Press,” Alternative Law Journal 41, no. 3 (2016): 160–164. ↩

-

Criminal Code 1995 (Commonwealth of Australia), ss 104 & 105; ASIO Legislation Amendment Act 2003 (Commonwealth of Australia); Lisa Burton, Nicola McGarrity, and George Williams, “The Extraordinary Questioning and Detention Powers of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation,” Melbourne University Law Review 36 (2007): 415; George Williams, “A Decade of Australian Anti-Terror Laws,” Melbourne University Law Review 35 (2011): 1136; Michael McHugh, “Constitutional Implications of Terrorism Legislation,” Judicial Review 8 (2007): 189. ↩

-

Australian Citizenship Amendment (Allegiance to Australia) Act 2015 (Commonwealth of Australia); Australian Citizenship Amendment (Citizenship Cessation) Bill 2019 (Commonwealth of Australia) Schedule 1, s 9, proposed s 36B–D; Leslie Esbrook, “Citizenship Unmoored: Expatriation as a Counter-Terrorism Tool,” University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law 37 (2015): 1273. ↩

-

Jenny Hocking, “Counter-Terrorism and the Criminalisation of Politics: Australia”s New Security Powers of Detention, Proscription and Control,” Australian Journal of Politics & History 49, no. 3 (2003): 355–371, 371. ↩

-

National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Act 2018 (Commonwealth of Australia), Schedule 5 (Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme); Schedule 1 amending Criminal Code 1995 (Commonwealth of Australia), ss 80, 90.1 (1), Subdivision B—Foreign interference, ss 92.2, 92.3. ↩

-

National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Bill, Explanatory Memorandum (Commonwealth of Australia), p. 174. ↩

-

The examples mentioned here are drawn from Michael Head, “Australia’s Anti-Democratic ‘Foreign Interference’ Bills,” Alternative Law Journal (2018) 43: 160–5, 161–63. ↩

-

See David Crowe, “Morrison’s Boycott Plan Sparks Free Speech Furore,” Sydney Morning Herald, November 2, 2019, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/morrison-s-boycott-plan-sparks-free-speech-furore-20191101-p536o1.html. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, Power/knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977 (New York: Vintage, 1980). ↩

-

See Philip Mirowski, Never Let a Serious Crisis Go To Waste (London: Verso, 2013). ↩

-

Bill McKubbin, “Big Oil is Using the Coronavirus Pandemic to Push through the Keystone Pipeline,” The Guardian, April 5, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/05/climate-crisis-villains-oil-industry-big-banks-pipelines; Peter Kreko, “The World Must not let Viktor Orban get Away with his Pandemic Power Grab,” The Guardian, April 1, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/1/viktor-orban-pandemic-power-grab-hungary. ↩

-

Katia Genel, “The question of biopower: Foucault and Agamben,” Rethinking Marxism 18, no. 1 (2006): 43–62. ↩

-

Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979, ed. Arnold I. Davidson, and Graham Burchel (Springer, 2008); Giorgio Agamben, Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm (Stanford: Stanford University, 2015). The distinction between bios and zoe—the human animal and the political animal—has been central to political theory since Aristotle: see Arendt, The Human Condition; Hannah Arendt, Between Past and Future. Eight Exercises in Political Thought (New York: Penguin Books, 1977). ↩

-

John Adams, “Economic Change in Italy in the Fourteenth Century: The Case of Siena,” Journal of Economic Issues 26 (1992): 125; William Bowsky, “The Impact of the Black Death upon Sienese Government and Society,” Speculum 39 (1964):1–34; William Caferro, “City and Countryside in Siena in the Second Half of the Fourteenth Century,” The Journal of Economic History 54 (1994):85–103. ↩

-

Millar Meiss, Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978); Henk Van Os, The Black Death and Sienese Painting: A Problem of Interpretation (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981). ↩

-

Giorgio Agamben, “Leviathan and Behemoth,” in Stasis, chapter 2, 272, 278. ↩

-

Jess Conditt, “Mobile Gaming Titans Keep Ripping Off Indies,” Engaget, November 7, 2018: https://www.engadget.com/2018/07/11/mobile-clones-app-store-google-play-indie-voodoo/ . ↩

-

Voodoo Games, Push “em all v. 1.10, © 2019 OHM Games SAS: see https://apps.apple.com/au/app/pushem-all/id1479551182 . ↩

-

For download and revenue data, see https://sensortower.com/ios/au/voodoo/app/push-em-all/1479551182/overview. ↩

-

Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, chapter 5, esp. 164–69; see also the seminal work on repressive desublimation in Herbert Marcus, One Dimensional Man (Boston: Beacon Press, 1964), 75–78. ↩

-

Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, 167. ↩

-

Brown, 180. ↩

-

Tom Conley, “Foreword,” in Louis Marin, Portrait of the King, trans. Martha House (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), vi, and Brown, In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, 6–7. ↩

-

Push ‘em all, screenshot of in-game ad, December 2019. ↩

-

Amongst many discussions, see Nick Dines, Nicola Montagna and Vincenzo Ruggiero, “Thinking Lampedusa: Border Construction, the Spectacle of Bare Life and the Productivity of Migrants,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38, no. 3 (2015): 430–445; Dougal Phillips, “The Asphyxia of the Image: Terror, Surveillance and the Children Overboard Affair,” Arena Journal 27 (2006): 81; Mary Macken-Horarik, “A Telling Symbiosis in the Discourse of Hatred: Multimodal News Texts About the ‘Children Overboard’ Affair,” Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 26, no. 2 (2003): 1–16. ↩

-

The connection here is surely to the ideological and political meaning of jouissance. See Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 79–84; see also Martin Müller, “Lack and Jouissance in Hegemonic Discourse of Identification with the State,” Organization 20, no. 2 (2013): 279-298; Paul Kingsbury, “Did Someboy say Jouissance? On Slavoj Žižek, Consumption, and Nationalism,” Emotion, space and society 1, no. 1 (2008): 48–55. ↩

-

Howard Caygill, On Resistance (London: Bloomsbury, 2013); Alessandro Bonnano, The Legitimation Crisis of Neoliberalism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017); Ugo Mattei, “Emergency-Based Predatory Capitalism: The Rule of Law, Alternative Dispute Resolution, and Development,” in Didier Fassin & Mariella Pandolfi, eds., Contemporary States of Emergency (New York: Zone Books, 2009), 24–25. ↩

Des Manderson is jointly appointed in the ANU Colleges of Law and of Arts & Social Sciences at the Australian National University. He directs the Centre for Law, Arts and the Humanities, designing innovative interdisciplinary courses with English, philosophy, art theory and history, political theory, and beyond, as well as pursuing collaborative projects with some of Canberra’s and Australia’s leading cultural institutions. His recent work pioneers new approaches to the intersection of law and the visual arts, notably in Law and the Visual: Representations, Technologies and Critique (Toronto 2018); and Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts (Cambridge, 2019).

Bibliography

- Abaza, Mona. “Shopping Malls, Consumer Culture and the Reshaping of Public Space in Egypt.” Theory, Culture & Society 18, no. 5 (2001): 97–122.

- Adams, John. “Economic Change in Italy in the Fourteenth Century: The Case of Siena.” Journal of Economic Issues 26 (1992): 125.

- Agamben, Giorgio. Stasis: Civil War as a Political Paradigm. Stanford: Stanford University, 2015.

- Alpers, Svetlana. Art of Describing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

- Arendt, Hannah. “Between Past and Future.” In Eight Exercises in Political Thought. New York: Penguin Books, 1977.

- Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

- Australian Citizenship Amendment (Allegiance to Australia) Act 2015 (Cth).

- Australian Citizenship Amendment (Citizenship Cessation) Bill 2019 (Cth).

- Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (Cth).

- Benhabib, Seyla. “Models of Public Space: Hannah Arendt, the Liberal Tradition and Jiirgen Habermas.” In Situating the Self: Gender, Community and Postmodernism in Contemporary Ethics, 89–120. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1992.

- Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1999.

- Bonnano, Alessandro. The Legitimation Crisis of Neoliberalism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Bottici, Chiara. Imaginal Politics: Images beyond Imagination and the Imaginary. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

- Bowsky, William. “The Impact of the Black Death upon Sienese Government and Society.” Speculum 39 (1964).

- Brion, Denis. “The Shopping Mall: Signs of Power.” In Law and Semiotics, edited by Roberta Kevelsen, 65–108. Boston: Springer, 1987.

- Brown, Wendy. In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. Columbia University Press, 2019.

- Brown, Wendy. “Neoliberalism’s Scorpion Tail.” In Mutant Neoliberalism: Market Rule and Political Rupture, edited by William Callison and Zachary Manfredi, 36–90. Fordham University Press, 2019.

- Brown v Tasmania [2017] HCA 43.

- Burton, Lisa, Nicola McGarrity, and George Williams. “The Extraordinary Questioning and Detention Powers of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation,” Melbourne University Law Review 36 (2007): 415.

- Button, Mark. “Private Security and the Policing of Quasi-Public Space.” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 31, no. 3 (2003): 227–237.

- Caferro, William. “City and Countryside in Siena in the Second Half of the Fourteenth Century.” The Journal of Economic History 54 (1994).

- Calhoun, Craig. Habermas and the Public Sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

- Campbell, C. Jean. “The City’s New Clothes: Ambrogio Lorenzetti and the Poetics of Peace.” The Art Bulletin 83, no. 2 (2001): 240–258.

- Castoriadis, Cornelius. The Imaginary Institution of Society [1975]. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997.

- Caygill, Howard. On Resistance. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

- Choudhury, Tufyal, and Helen Fenwick. “The Impact of Counter-Terrorism Measures on Muslim Communities.” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 25 (2011): 151–81.

- Clun, Rachel and Jacob Saulwick, “Alan Jones Calls on Berejiklian to Sack Opera House Boss over Racing Dispute.” Sydney Morning Herald. October 5, 2018.

- Conditt, Jess. Mobile Gaming titans Keep Ripping Off Indies, 2018. https://www.engadget.com/2018/07/11/mobile-clones-app-store-google-play-indie-voodoo/.

- Conley, Tom. Foreword,” in Louis Marin, Portrait of the King. Translated by Martha House. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

- Counter Terrorism Legislation Amendment (Foreign Fighters) Act 2014 (Cth).

- Criminal Code 1995 Act (Cth).

- Dahlberg, Leif. “Factoring Out Justice. Imaginaries of Community, Law, and the Political in Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Niccolò Machiavelli.” Lychnos, 2013, 35–73.

- Damisch, Hubert. L’origine de La Perspective. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

- D’Entrèves, Maurizio. “Hannah Arendt and the Idea of Citizenship.” In Dimensions of Radical Democracy: Pluralism, Citizenship, Community, edited by Chantal Mouffe, 145–168. London: Verso, 1992.

- Dines, Nick, Nicola Montagna, and Vincenzo Ruggiero. “Thinking Lampedusa: Border Construction, the Spectacle of Bare Life and the Productivity of Migrants.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38, no. 3 (2015): 430–445.

- Ellis, Markman. The Coffee House: A Cultural History. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2004.

- Ellis, Markman, Desmond Manderson, and Sarah Turner. “Introduction to the Coffee-House. A Discursive Model.” Law and Social Inquiry 31 (2006): 649–76.

- Esbrook, Leslie. “Citizenship Unmoored: Expatriation as a Counter-Terrorism Tool.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law 37 (2015): 1273.

- Ethington, Philip. The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Vintage, 1980.

- Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979. Edited by Arnold I. Davidson and Graham Burchel. Springer, 2008.

- Frisby, David. “The Flâneur in Social Theory.” In The Flaneur (RLE Social Theory), 81–110. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Genel, Katia. “The Question of Biopower: Foucault and Agamben.” Rethinking Marxism 18, no. 1 (2006): 43–62.

- Goheen, Peter. “Public Space and the Geography of the Modern City.” Progress in Human Geography 22, no. 4 (1998): 479–496, 482–3.

- Habermas, Jürgen. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. London: John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1963]. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

- Hayek, Friedrich. Studies in Philosophy, Politics and Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967.

- Head, Michael. “Australia’s Anti-Democratic ‘Foreign Interference’ Bills.” Alternative Law Journal 43 (2018): 160–5.

- Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan [1651]. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2017. – Hocking, Jenny. “Counter-Terrorism and the Criminalisation of Politics: Australia”s New Security Powers of Detention, Proscription and Control.” Australian Journal of Politics & History 49, no. 3 (2003): 355–371.

- Howell, Philip. “Public space and the public sphere: political theory and the historical geography of modernity.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11, no. 3 (1993): 303–322, 314.

- Iversen, Margaret. “The Discourse of Perspective in the Twentieth Century: Panofsky, Damisch, Lacan.” Oxford Art Journal 28, no. 2 (2005): 191–202.

- Kingsbury, Paul. “Did somebody say jouissance? On Slavoj Žižek, consumption, and nationalism.” Emotion, space and society 1, no. 1 (2008): 48–55.

- Kreko, Peter. “The World Must Not Let Viktor Orban Get Away with His Pandemic Power Grab.” The Guardian, April 1, 2020.

- Lippens, Ronnie. “Gerard David’s Cambyses [1498] and Early Modern Governance: The Butchery of Law and the Tactile Geology of Skin.” Law and Humanities 1 (2009): 1–24.

- Macken-Horarik, Mary. “A Telling Symbiosis in the Discourse of Hatred: Multimodal News Texts about the ‘Children Overboard’ Affair.” Australian Review of Applied Linguistics 26, no. 2 (2003): 1–16.

- Marcus, Herbert. One Dimensional Man. Boston: Beacon Press, 1964.

- Mattei, Ugo. “Emergency-Based Predatory Capitalism: The Rule of Law, Alternative Dispute Resolution, and Development.” In Contemporary States of Emergency, edited by Didier Fassin and Mariella Pandolfi, 24–25. New York: Zone Books, 2009.

- McKubbin, Bill. “Big Oil Is Using the Coronavirus Pandemic to Push through the Keystone Pipeline.” The Guardian, April 5, 2020.

- Meiss, Millar. Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death: The Arts, Religion, and Society in the Mid-Fourteenth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

- Mensch, James. Embodiments: From the Body to the Body Politic. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2009.

- Mirowski, Philip. Defining Neoliberalism. Edited by Philip Mirowski and Dieter Pluhwe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Mirowski, Philip. Never Let a Serious Crisis Go To Waste. London: Verso, 2013.

- “Morrison’s Boycott Plan Sparks Free Speech Furore.” Sydney Morning Herald, November 2, 2019.

- Müller, Martin. “Lack and Jouissance in Hegemonic Discourse of Identification with the State.” Organization 20, no. 2 (2013): 279–298.

- National Security Legislation Amendment Act (No. 1) 2014 (Cth)

- National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Act 2018 (Cth)

- Explanatory Memorandum, National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Bill 2018 (Cth).

- Os, Henk Van. The Black Death and Sienese Painting: A Problem of Interpretation. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981.

- Panofsky, Erwin. Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books, 1991.

- Philip Mirowski, Quoted, and Dieter Pluhwe, eds. In The Road from Mont Pelerin, 328. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Phillips, Dougal. “The Asphyxia of the Image: Terror, Surveillance and the Children Overboard Affair.” Arena Journal 27 (2006): 81.

- Philo, Chris. Of Public Spheres & Coffee Houses, n.d. http://web.geog.gla.ac.uk/online_papers/cphilo015.pdf.

- Riot Act 1714 (UK) 1 Geo 1, c 5, s 2.

- Rubinstein, Nicolai. “Political Ideas in Sienese Art: The Frescoes by Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Taddeo Di Bartolo in the Palazzo Pubblico.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 21 (1958): 179–207.

- Sawyer, Stephen, Daniel Steinmetz–Jenkins, Neoliberalism Foucault, and Beyond, 2019.

- Sennett, Richard. Flesh and Stone: The Body and the City in Western Civilization. New York: WW Norton & Company, 1996.

- Skinner, Quentin. “Ambrogio Lorenzetti: The Artist as Political Philosopher.” In Proceedings of the British Academy, Vol. 72, 1986.

- Skinner, Quentin. “Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Buon Governo Frescoes: Two Old Questions, Two New Answers.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 62 (1999): 1–28.

- Summary Offences and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2019 (Queensland), Ss.2–6, Amending Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000 (Queensland, n.d.

- Thompson, John. “Ideology and the Social Imaginary: An Appraisal of Castoriadis and Lefort.” Theory and Society 11, no. 5 (1985): 659–681.

- Voyce, Malcolm. “Shopping Malls in Australia: The End of Public Space and the Rise of ‘Consumerist Citizenship’?” Journal of Sociology 42, no. 3 (2006): 269–286.

- Wacquant, Loïc. “Crafting the Neoliberal State.” Sociological Forum 25 (2010): 202.

- White, John. The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space. London: Faber & Faber, 1957.

- Whyte, Jessica. The Morals of the Market. London: Verso, 2019.

- Williams, George, Kieran Hardy, and George Williams. “The Legal Assault on Australian Democracy.” Queensland University of Technology Law Review 16: 19, no. 3 (2016): 28–29.

- Williams, George, and Michael McHugh. “A Decade of Australian Anti-Terror Laws.” Melbourne University Law Review 35 (2011): 189.

- Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Amendment Bill 2019 (Cth).

- Yeats, W.B. “Among School Children.” In Collected Poems, edited by Richard Finneran, 222. New York: Scribner, 1996.

- Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso, 1989.

- Zukin, Sharon. Cultures of Cities. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.