Clothes Maketh the Man Mimesis, Laughter, and the Colonial Rule of Law

When the Anglo-Australian artist, Samuel Thomas Gill, died in Melbourne in 1880, he left behind one of the most telling archives of nineteenth century Australia, a body of work—watercolours, sketches, lithographs—that bears witness to the everyday life of settler-colonialism in the country.1 Left behind in stone, in print, in sheet after sheet, are the traces of a social history of Australia’s south-eastern colonies, mediated by an artist who wandered these southern landscapes, urban and outback, observing their smallest details with a sensitivity to the violent contradictions of colonisation. Part of the aim of this article is to draw out one of those contradictions in Gill’s painting, Native Dignity (1860)—a contradiction that exposes the racialised violence of the colonial “rule of law.” But more than just how that contradiction is registered in Gill’s painting, the article is concerned with how the contradiction is innervated by the artwork—how Native Dignity confronted its European audiences in the Australian colonies with nerve-force, unsettling the conception of equality that both promises and is the promise of the rule of law.

In this, the aim is to understand how Gill’s painting is not only historically produced, but also histrionically productive. By this I mean two things. For one, “histrionic production” suggests a public performance, and more specifically, the performance of a histrio, or pantomime, whose role it is, traditionally, to represent society’s mythologies through burlesque or a related mimetic form. But there is also a physical meaning at play here, for a “histrionic spasm,” in medical terms, refers to the way in which a body convulses against itself when innervated; to wit: “The contortion of features and the furious expression of face presented by maniacs is the uncontrollable play of the histrionic muscles.”2 What these two meanings suggest is that, to read a painting histrionically is to examine how it performs mimetically for an audience, in a way that causes the audience a great deal of discomfort, stimulating spasms in the social body by revealing its immanent contradictions.

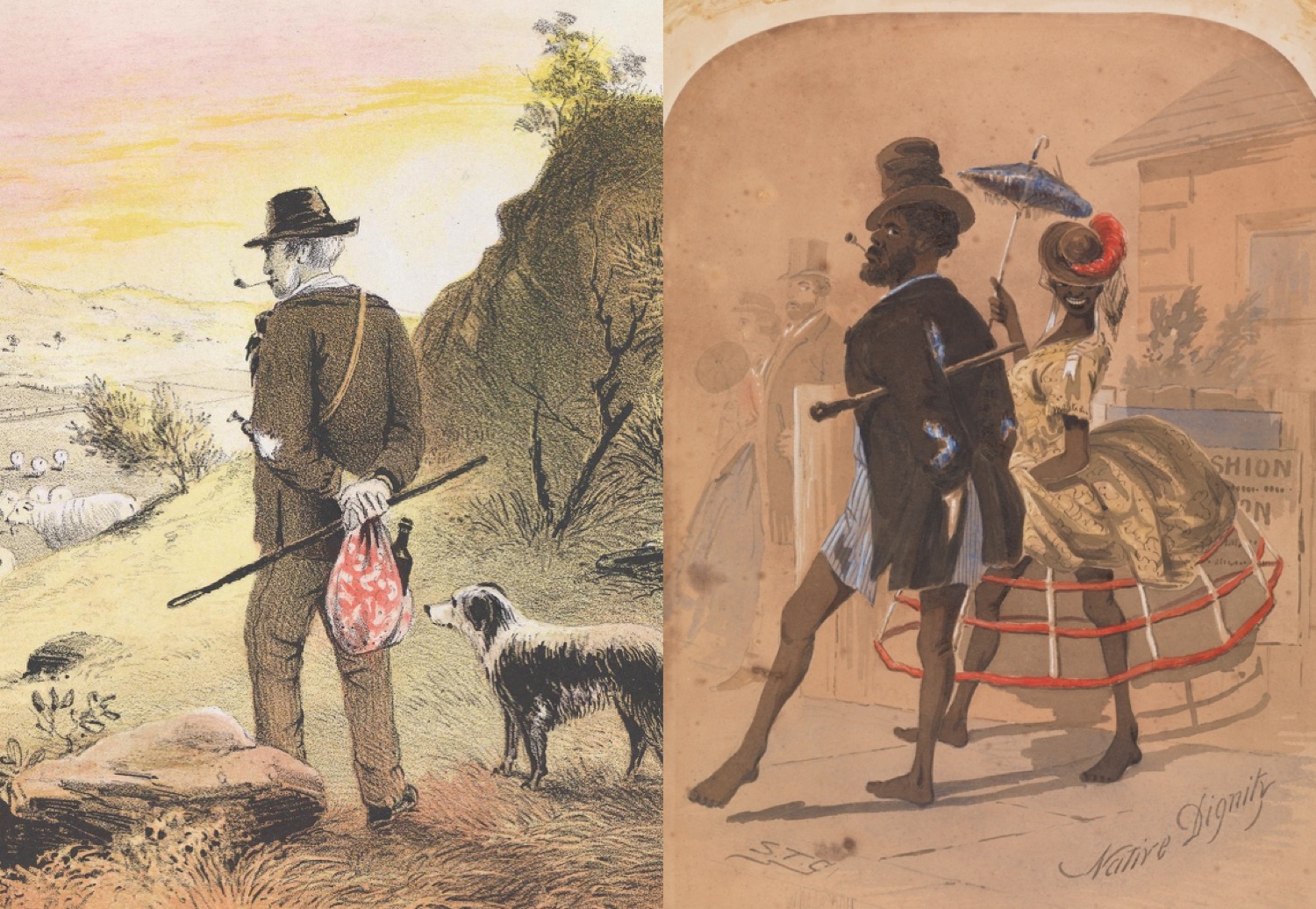

Before proceeding with this dual historical-histrionic reading, it is perhaps helpful to take a preliminary look at Native Dignity (fig. 1). This painting was part of a series of satirical pieces that Gill created in the late 1850s, based on his time in Melbourne and Sydney, which he apparently intended to publish together as a book titled “Colonial Comicalities.”3 It depicts an Aboriginal couple walking along the pavement of a city street dressed in European clothes in a manner that would have appeared highly improper to a European eye. In the background a European couple can be seen walking up a side street, their path about to cross the path of the Aboriginal couple, who are only a few steps away. The European couple have noticed the Aboriginal couple; they watch them uncomfortably out of the corner of their eye, obviously unsettled by the scene but seemingly unsure how to respond. The Aboriginal couple are not looking their way, however. Their heads are turned so as to face the audience; and as they look out of the painting, their faces, and especially their eyes, appear to be laughing, mocking, ridiculing, as if they are playing a joke on the European couple in the scene—as if they are burlesquing them, mimicking their fashion, mimicking their movements, mimicking their very presence there. In this, the Aboriginal couple appear centre-stage; they walk tall, proud; they look their audience in the eye defiantly, a defiance that not only conveys resistance to European domination, but also asserts their own power and authority. This couple are not “mimic men”—they are not mimicking the colonists in order to become European.4 They are mimicking the colonists in almost every aspect: their clothes almost mirror those of the European couple in the painting, the parasols and walking sticks almost reflect each other, their postures too—the feet of the two men are almost synchronised. But not quite.

If this article has a dominant refrain, it is this act of mimicry, which, as we shall see, ultimately poses the critical response to the “not yet” aspect of the rule of law, to its ever-deferred promise of equality before the law.5 Indeed mimesis, of both imperial and critical kinds, appears at every turn to be at work here, in the art as much as in the law. Or to put that another way, both art and law appear to work mimetically, not just in the simple sense of being representational of the world, but also, and much more interestingly, in the sense of making the world through its representation (which is also to say, its misrepresentation).6

What might be of interest in this to art historians is the new reading it offers of Gill’s artwork. Of interest to scholars of law might be what this reading reveals about the concept of dignity, a core legal concept in the field of human rights,7 but also one that is implicated in the modern concept of the rule of law. The main contribution, however, is to the interdisciplinary field of “law and the humanities,” as a study of modern law’s social and cultural archive, and of its everyday life in a settler-colony. Thus, on one hand, the article contributes to an understanding of how social history and art history are legal history, insofar as the discourse of dignity that is layered in Native Dignity is deeply implicated in a civilising mission that involves the transformation of Australia’s Indigenous peoples. And, on the other hand, as a study of the everyday life of law, the article adds to an understanding of how modern law works, not only through official institutions such as police and courts, but also through public discourses, practices, and other cultural forms of expression, including artwork—and how art in turn can work against that law.8

An Exhibition

The following scene played out a little over a year before the 21-year-old Samuel Thomas Gill arrived in the colony of South Australia from England, and a little less than two years after the Proclamation of the colony was read out on Kaurna Country (making it, on the colonists’ calendar, late 1838). The occasion has been described variously by the colonists as a “festival” and a “feast” for the “Adelaide tribes,” hosted by the newly-arrived British Governor, George Gawler. Following “three hearty cheers” for the some 200 gathered Kaurna people, the Governor addressed them with a speech:

Black men! We wish to make you happy. But you cannot be happy unless you imitate good white men, build huts, wear clothes, work, and be useful. Above all things, you cannot be happy unless you love God, who made heaven and earth and men and all things. Love white men. Love other tribes of black men. Do not quarrel together. Tell other tribes to love white men, and to build good huts and to wear clothes.9

Another colonist simply recalls the Governor telling the Kaurna “to become good British subjects—give up eating each other—dress in proper clothing (for they generally went about stark naked), and love all white people, &c, &c,”10 to which the shouted response was heard, “Varey goodey, cockatoo Gubner,”11 in reference to the plume of white feathers that crested the Governor’s hat (a reference that “was always afterwards used by the natives when speaking of him”).12

The final event of the day was a spear-throwing exhibition, and it was here, according to one of the colonists, that the Kaurna “completely out-generalled Colonel Gawler.”13 The exhibition was led by the famous Kaurna elder and warrior, known to his peers as Mullawirraburka, meaning, in contemporary terms, the “senior custodian of the Willunga area.”14 Known to the colonists as “King John,” Mullawirraburka was invited to inspect the targets that had been set out “at suitable and fair distances” for the exhibition.15

King John first made a grave and dignified inspection of the target at the farther end, and returning half-way towards the attacking position paused, measuring the distance with his eyes, and returned, shaking his head, to the starting-point where his men and the company were standing. He then said: “No, no, too much long way.” The distance was not 100 yards. [ … ] [A]t or about sixty yards he consented to try their skill, though he with admirable acting expressed his doubts. Now fixing his womera (a casting agent for long distances), amidst the objecting grunts of his tribe, he discharged his spear so as to strike the rim of the target with the middle of the spear instead of the point, and then came the ejaculations of his men, implying, “Ah! ah! we told you so!” Then came up in turn the warriors of the tribe, but with well-expressed reluctance, some just missing the target, others following the example of King John; and now they pretended shame under the derisive cheers of the lubras. The boomerangs were then thrown high, and so as, in their eccentric flight, to return towards those who cast them, and appeared more calculated to endanger the thrower than an opponent. On this many of the ladies exclaimed, “Poor fellows, you see they cannot hit anybody even at that short distance,” and many of the spectators were convinced of the harmless character of the warriors amongst whom we had arrived.16

The joke, however, was not missed on this writer:

If they laughed at us on the sly before us, it was internally and well disguised. No doubt the joke circulated far and wide amongst the surrounding tribes, and most likely formed the subject of one of their corroborees, their custom being to rehearse with musical accompaniment any striking occurrence, the accompaniment being performed by women beating sticks together, and uttering “Ah, ah, ah, ah,” continually during the dancing of the males.17

And yet, if we are to believe another account, the writer missed the punchline:

The targets were fixed at last, at about forty paces distant. Captain Jack, King John, and several other aboriginals now tried their prowess at the targets, but not a spear touched them. Many fell short of the distance, and this elicited much derisive laughter amongst the bystanders, and made King John very excited. He suddenly stripped off his red woollen shirt and moleskin pants, appeared in full Adamite costume, and before any one could interfere he gave a tremendous yell and dashed two of his spears right through the centre of the target. Then turning quickly round to the spectators, many of whom were making a rapid departure, with His Excellency and party leading, he pointed to the target and shouted, “Varey goodey,” and then, shaking his fist at his clothes thrown on the ground, “no goodey.”18

At the outset of the festival, the Kaurna had been given European shirts, trousers, frocks, and blankets to wear. Now, having clowned around in the colonists’ clothing like the carnival buffoon, acting harmless, impotent, pathetic, eliciting mirth and derision in equal measure, Mullawirraburka made his point—stripping away the colonisers’ clothes before dashing with “a tremendous yell” not one but two of his spears “right through the centre of the target,” followed by that same shout, this time stripped of its irony—varey goodey!—which had earlier answered the Governor’s speech. And finally, in case the European audience was left in any doubt about the source of his power, and the source of his earlier impotence, Mullawirraburka ended the exhibition by effectively pissing on their Civilisation, represented in the crumpled figure of the shirt and pants discarded in the dust. Who, you can almost hear him calling out to the rapidly departing party, is the real clown here, me or the Cockatoo Governor?

Moral Fibres

Clothing, as a medium that both expresses an identity and impresses on the body that wears it an identity—and here you might think of how uniforms create certain subjects—was understood by the colonists to be an effective tool for transforming Aboriginal people into “good British subjects.”19 For example, at a “Public Meeting in Aid of the German Mission to the Aborigines,” held in South Australia in 1843, the colonist Anthony Forster reportedly rose to address the work that was being done “to rescue the hapless natives of this country from the degradation in which they were found.”20 After admonishing the colonial government for “permitt[ing] the natives to go about the streets in a state of nudity,” Forster suggested a way to redeem the South Australian colonisation project: if the colonists “could give them [Aboriginal people] a nearer approach to humanity by clothing them,” he pronounced, “if they could make them look like men—they would then, perhaps, begin to think like men.”21 In similar fashion, the British man Robert Harrison, in his book Colonial Sketches, which draws on Harrison’s experiences living in South Australia from 1856 to 1861, reflected on “the influence of dress as an agent of civilisation” before cautioning his readers that “the disregard of the decencies of clothing and a neglect of cleanliness generally tend to the utter demoralisation of the subject” (and so, by implication, a proper regard for clothing leads to the moralisation of the subject).22

What these British men seemed to have understood is that clothes are not just a physical form for covering the body, but—like Aboriginal body paint—also a normative force for constituting subjects; that clothing the body might work well to keep the frost from biting, but can work just as well to “moralise” or to “humanise,” which was to say the same thing. And they surely were not the only colonists to understand, at least intuitively, what Michel Foucault would later theorise in terms of disciplinary power.23 What Forster got wrong, however, was that the colonial government had been complacent in “permitting” Aboriginal people “to go about the streets in a state of nudity.”24 Governor Gawler’s administration, like the colonial administrations before and after, required Aboriginal people to wear European clothes. If they would not do so voluntarily, then “there existed an admirable and efficient town police, formed by officers from, and on the model of the London Police”—as Gawler reminded the South Australian colonists in a public response to Forster—with “express orders to prevent the natives from entering the town without decent covering.”25

And yet, to the colonists’ enduring frustration, Aboriginal people were anything but docile recipients of the gifts of Civilisation. As Governor Gawler discovered at his (un)welcome ceremony, Mullawirraburka’s response to the British assertion of sovereign authority was to play a joke on the colonists that involved a kind of burlesque. The colonists’ stories about that day create the impression of a histrionic performance put on by the Kaurna, which first used parody to subvert the colonial overture (a word, it should be highlighted, that has both legal and theatrical meanings, as the act that seeks to set the terms of a new relationship, and the act that precedes the main performance), before ultimately casting the imperial-mimetic framework aside altogether. That is, after appearing to play (with) the colonists by counter-posing the figures of “copy” and “original” and complicating the relation between them to critical effect, in the end the Kaurna were seen to counter-pose their own originality to that of the Europeans. Especially telling is the colonists’ anxiety that the Kaurna would then repeat their performance at a corrobboree, re-enacting the exhibition for other tribes through song and dance, thereby immortalising the humiliation of the Europeans and the power of the Kaurna in a mythology that would spread like wildfire through the bush.26

This is not the only time that the colonists expressed anxiety about being laughed at by Aboriginal people. As one colonist recalls, shortly after the arrival of their ship from England, the initial band of South Australians had their introductory encounter with a riot of kookaburras, whose laughter they mistook for an act of war. “The new arrivals early in the morning had been greatly astonished by the clamour of a number of laughing jackasses, as those birds (a variety of the kingfisher) are called. At first some of the people believed the blacks were laughing at them, and had arrived to make an attack.”27 Many other references in the colonial archive suggest the colonists were highly sensitive about being “ridiculed,” or “jeered at,” by Aboriginal people.28 Harrison, in his Colonial Sketches, commented directly on this, remarking that the “so-called savages” would use their “dry sense of humour” to counter the attempts of European missionaries to “civilise” them.29 So great was Harrison’s belief in the power of laughter that he included on the title-page of his book the phrase castigat ridendo mores—laughter corrects mores, which is to say, ridicule disciplines—which, for Harrison, appeared to cut both ways. To the extent that humour worked to assimilate (to change manners, morals, laws—the very ways of life), it also worked to counter assimilation.

If the colonists saw mimesis as the battleground on which colonisation was fought at Governor Gawler’s festival, then clothing was the weapon chosen by both sides. However, 1838 in South Australia was a very different time and place to 1860 in New South Wales. By the time Gill added the last touches to Native Dignity in Sydney, Aboriginal peoples on the east coast had been hammered by close to a century of genocidal colonisation. For an Aboriginal man or woman to strip away their European clothes in Sydney at this time would have been to face severe punishment at the hands of the colonists. For very many Aboriginal people in mid-nineteenth century colonial Australia, wearing European clothes had become a matter of survival.30 And yet, even still, Aboriginal people resisted this mode of assimilation. Throughout the nineteenth century, colonists expressed constant concern with what they saw as the failure of Aboriginal people to dress in European clothes properly. As the Reverend George Taplin wrote in 1873, in recalling his time as a Christian missionary in South Australia: “Our congregations at first were often strangely dressed.”

Some of the men would wear nothing but a double-blanket gathered on a stout string and hung round the neck cloakwise, others with nothing but a blue shirt on, others again with a woman’s skirt or petticoat, the waist fastened round their necks and one arm out of a hole at the side; as to trousers, they were a luxury not often met with.31

Taplin ends his reminiscence by recalling one especially shocking Sunday sermon. “To our horror and dismay one Sunday a tall savage stalked in and gravely sat down to worship with only a waistcoat and a high-crowned hat as his entire costume.”32 Even more than stark-nakedness, it was this—the “combination of dress and undress,” the “tatterdemalion upending of every expectation”—that seemed to disturb the Europeans most.33 Half-dressed, cross-dressed, dressed-up in tattered clothes, Aboriginal people appeared to the Europeans neither Savage nor Civilised, exhibiting traits of both at once.

In her study of “Aboriginal Men and Clothing in Early New South Wales,” Grace Karskens documents the outrageous ways in which Aboriginal men would customise European clothes.34 One image in particular recurs in this archive: the Aboriginal man wearing a blue shirt and jacket, without trousers.35 As early as 1819, a group of French men “noted with some shock that this was the usual manner of dress for the Aboriginal men in Sydney,” and it was apparently a fashion that persisted, at least in the mind of the colonist, well into the nineteenth century.36 Another image that clearly left an impression was that of the Aboriginal man and woman walking the streets in European “finery.” In one account, a German man who spent ten months in South Australia between 1849 and 1850 wrote of his encounter with “a young beauty whose long cotton dress swept the dust for half an ell behind her and a ‘black dandy’ [who] seemed to enjoy his appearance in his finery consisting of white shirt, vest, cravat with collar and once-white gloves.”37 In this man’s eyes, the result was a “comical appearance.”38 And he was not the only European to say so. Laughing at Aboriginal people was one of the main ways in which the colonists’ anxiety manifested—a laughter mixed with “horror and dismay” (in Reverend Taplin’s words).39 As Karskens also notes, “ridicule, sometimes mingled with horror and disgust,” was an especially prominent response to Aboriginal people’s customisation of European clothes.40 Karskens cites as an example a European man who, on seeing an Aboriginal man with an old Russian greatcoat “flapping around his chest,” described him as “bowing and scraping, his grotesque way of dressing ma[king] him look even more ridiculous.”41 One can imagine the contortion of features and furious expression of face as he laughed maniacally at the image. Castigat ridendo mores. The colonists might have feared the power of Aboriginal peoples’ humour to counter assimilation, but they also understood the power of humiliation to force assimilation.

Native Dignity as Representation

All of this—the attempt to ridicule the uppity pretensions of the natives, while reinforcing the relation between clothing them and civilising them—is represented in Gill’s painting of Native Dignity. The image of Aboriginal people dressed-up in a state of undress, to a European eye the epitome of the grotesque, is once more on display. Again one sees foregrounded the stock-image of the Aboriginal man wearing a blue shirt and jacket without trousers, the Black Dandy, walking alongside a Young Beauty whose crinoline dress (wildly fashionable among Europeans in the late 1850s) is hitched half way up the hooped cage; while in the background the colonists’ anxiety is apparent. But if this is a representation of that worn colonial discourse, then what is the connection with the two words that make up the title, “native dignity”?

As it turns out, they are not just two words, but a concept, and a concept that would have had a very specific meaning for Gill and his European audiences in both Europe and the Australian colonies. At the time, in its immediate, common-sense usage, “native dignity” was synonymous with “natural dignity,” signifying a quality possessed equally by all humans on the basis of being human, in contrast with what was sometimes called “artificial dignity,” a quality possessed unequally by a few on the basis of social status.42 An 1845 edition of Sydney’s Sentinel newspaper offers an especially poetic example:

Frank possessed that native dignity which poverty cannot slide, nor wealth bestow, and which, when the heart beats proudly, although beneath a thread-bare coat, will still reveal the aspect of a gentleman.43

Or as another New South Wales newspaper wrote in 1881, of the “titled loafers” in the British House of Lords, whose “native dignity” had been “strangled” by “an artificial dignity thrown over [them] like a newly-washed garment thrown over a dirty skin. It covers the man, but forms no part of his nature, like true inherent dignity.”44 Humans were not alone in possessing native dignity. Beasts were also understood to have a native dignity that is proper to their taxonomic class.45 Savages too.46 What distinguished the native dignity of humans from that of beasts and savages, however, is that, in the words of one colonial newspaper, it is a property that “belongs to a man created in the image of God.”47

While the term was used throughout the nineteenth century in everyday Anglophone parlance in this way, to refer to an intrinsic property that is most apparent when the human form is in its God-given, native-born state, uncovered by society’s finery, the term’s popular meaning was forged at the end of the eighteenth century in the heat that radiated out from the American and French revolutions. Mary Wollstonecraft in particular helped to popularise the term in her defence of the revolution in France.48 In her widely-read polemic, A Vindication of the Rights of Men, published in 1790, Wollstonecraft argued for what she called the “native dignity of man,”49 which she conceptualised as a potential that all humans possessed by virtue of being human.50 Wollstonecraft’s human-based concept of dignity was a direct response to Edmund Burke’s attack on the French Revolution, in which he defended a longer tradition of thinking about dignity as status-based.51 Dignity in this tradition is a property of position, of rank or office, and not a property of the human.52 As an influential English dictionary from the early eighteenth century noted: “dignity” is a matter of “rank of elevation” that is “properly represented by a lady richly clothed, and adorned”—connecting it simultaneously to the title of lady and the manner of dress that is proper to such an elevated position.53 Because of this, as Michael Meyer writes, “not only is dignity not an apt mark of the common man” or woman for thinkers like Burke, but “any such illicit usurpation of dignity is an occasion for ridicule.”54 To use one of Burke’s own terms, any commoner who tried to exhibit dignity, for example by wearing the dress of a lady without possessing the title of lady, would look like a “clown”;55 or as Meyer puts it, summarising Burke’s position: “Since common men and women are not born into the position in society that is granted the training necessary for ranking members of society, they can have dignity only in a foolish or grotesque way.”56

Looking again at Gill’s painting, one can see reflected in it this Burkeian understanding of dignity. At first sight, Native Dignity appears to ridicule the Aboriginal people who could be seen walking the streets of Sydney and Melbourne, castigating them for illicitly usurping dignity by dressing in the fashion of high-class Europeans. Castigat ridendo mores. And yet this is clearly not an image that simply affirms a Burkeian concept of status-based dignity by drawing satirical attention to the clownish figure of the dressed-up native. Against such a reading, the painting gives the distinct impression that the Aboriginal couple, who for Burke could have dignity “only in a foolish or grotesque way,”57 have dignity, and have it precisely in a foolish or grotesque way. They act the clown with a knowing nod to their audience, and in doing so, like Mullawirraburka, are seen to be dignified; while the European couple in the painting, who act dignified, appear, like the Cockatoo Governor and his party, the tragic characters of the piece, remaining “totally oblivious,” as Sasha Grishin writes, “to the ridiculous nature of their own outfits.”58

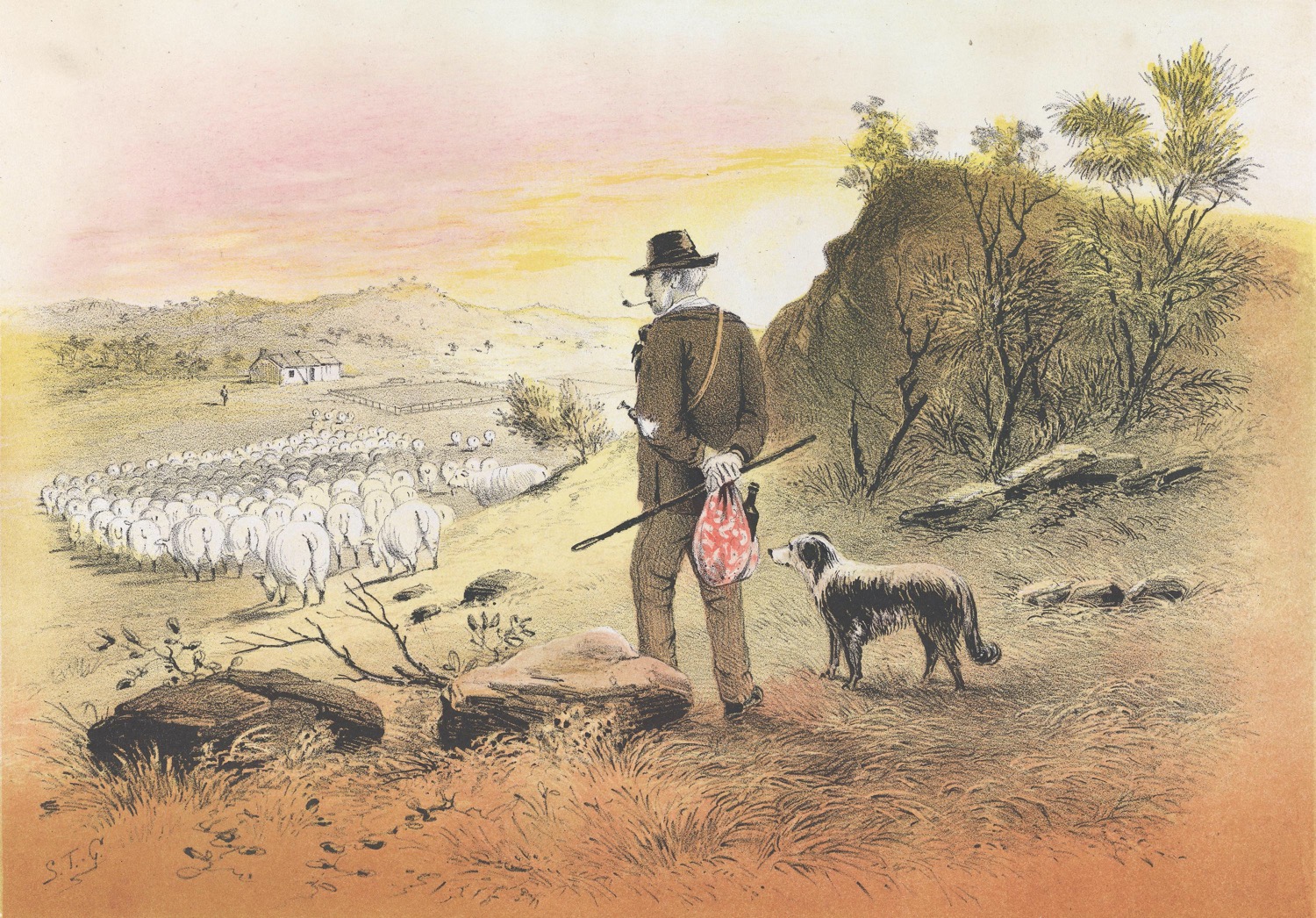

This is clearly not a simple affirmation of Burkeian status-based dignity—but nor is it simply an affirmation of that native dignity “which poverty cannot slide, nor wealth bestow,” that natural human-based dignity that is most apparent when the body is covered by only “a thread-bare coat.”59 To see this, it helps to look at the painting alongside another of Gill’s pictures, Homeward Bound (fig. 2).

This colour lithograph was published in Melbourne in 1864, four years after Native Dignity, in one of Gill’s Australian myth-making masterpieces, The Australian Sketchbook. It depicts a European man of apparently modest means herding sheep through a country landscape towards their night paddock. Dressed in a thread-bare coat, the man makes the final familiar paces of the day without need for his walking stick, which he holds behind his back. From the rise he gazes down into the valley, hat pulled low to shade his eyes from the setting sun; and as he contemplates the scene, a soft wisp of smoke rises from his pipe as if to the meandering rhythm of the sheep. Now look again at Native Dignity. It does not take a keen eye to see the similarities, and more importantly, the differences. The figures of the two men, one white, one black, are almost identical; dressed in similar tattered coats, walking sticks held at similar angles behind their backs, pipes in mouth, hats on, they walk in almost perfect synchrony. Almost, but not quite. The white man walks in a private rural setting all-but alone with his dog; the black man walks in a public urban street with his female companion, about to collide with two pedestrians. The white man is dressed in trousers and shoes; the black man wears neither. The white man’s pipe smolders; the black man’s is propped, askew and unlit, between his lips. The white man’s head is turned away, his eyes looking off into the distance; the black man’s head is turned to his audience, chin up defiantly, his eyes simultaneously commanding and demanding a response. Above all, the white man is white, the black man, black.

The juxtaposition of these two images (fig. 3) illuminates a contradiction in the concept of native dignity that arrived in the Australian colonies along with the colonists. On one side, Homeward Bound registers the ease with which Europeans could speak of the native dignity of the human as a universal concept that means the same for everyone at all times and places, when facing a European man. Looking at the image of this man—call him Frank—another European man could easily say: despite his thread-bare coat, he still possesses that native dignity which poverty cannot slide, nor wealth bestow. In contrast, Native Dignity registers the unease that a European would have felt in speaking of the native dignity of the human as a universal concept when face-to-face—indeed eye-to-eye—with Aboriginal people. The native dignity of the human was supposed to be most apparent when the body is covered by only a thread-bare coat, and least apparent when covered by fine garments—but the opposite was considered to be true for Aboriginal people. While Frank’s native dignity would be “strangled” by a newly-washed garment,60 an Aboriginal man had to wear that newly-washed garment in order to exhibit the same native dignity. For an Aboriginal man to be dressed in only a thread-bare coat, or for an Aboriginal woman to be dressed in a scandalously-worn dress, legs and feet exposed, would have signified, not native dignity, but abject degradation. In brief, to possess the native dignity that Europeans naturally possessed, by virtue of being human, Aboriginal people had to first look the part. Naked, Aboriginal people had the native dignity of the Savage; dressed properly in European clothes, they would at least exhibit the native dignity of the human; but dressed-up in a state of undress, Aboriginal people exhibited neither the native dignity of the one nor of the other. To appear in such a state, half-dressed, was to remain half-human, the most degraded of forms.

Native Dignity displays this unsettling truth—that “native dignity,” that revolutionary human-based concept, was actually a retrograde status-based one. For Europeans, native dignity was supposed to be a radical, egalitarian, emancipatory concept, set against a long tradition of thinking about dignity as a matter of “rank of elevation” that “is properly represented by a lady richly clothed, and adorned.”61 And yet for Aboriginal people, it was exactly that: a matter of rank of elevation that was properly represented—and brought about—by wearing European clothes. For Aboriginal people, the concept either arrested their dynamism as peoples by tying them to a scientistic image of the Noble Savage, or else totally dynamited their existence as peoples by trying to transform them in the image of the Dignified Human. Failing to conform to either image meant not having a native dignity at all—the birth right of all animate life; while conforming to either image meant being sub-human or else being remade in the image of European Man, that “rational” being made in the image of God.62 The result, on full display in Native Dignity, was a concept of dignity even more dominating than the Burkeian status-based one that it was supposed to overcome. For the antipodal Savage, the consequence was that their only hope for having “human dignity” was to undergo a dramatic transformation, beginning with the first rite of every day: getting dressed. In the words of the South Australian colonist, Robert Forster, the only hope was to “give them a nearer approach to humanity by clothing them,” for “if they could make them look like men—they would then, perhaps, begin to think like men.”63 From moral fibre to moral fibre.

Re-presentation

If one had to identify the genre of Native Dignity, it would be a visual paronomasia—a pun. The title of the painting, inscribed on the sidewalk at the bottom-right of the image, evokes the concept of “native dignity,” the immediate meaning of which, for Gill and his European audiences, was “natural dignity.” But by drawing these words together with an image of Aboriginal people, the picture suggests a second meaning: “native dignity” as “dignity of the natives.” Now, if the natives in the painting were naked, or if they were dressed properly in European clothes, then Native Dignity would be merely a sympathetic illustration of the concept, and not a pun; it would have the mimetic effect of creating identity between concept and image, rather than non-identity, which is crucial to the pun form. Instead, Native Dignity illustrates a contradiction in the concept, by representing natives without native dignity—natives who, in order to possess that natural property of every species, would have to exhibit either the artifice of the European, or the artifice of the Savage. The result is a painting titled Native Dignity that shows what the two words obscure, the concept’s conceit, the artificial nature of “native dignity.” At the same time, the painting presents a critique of Burkeian status-based dignity, by drawing attention to the ridiculousness of the “dignified” Europeans, and the dignity of the “ridiculous” Aboriginal people. In this way, Native Dignity neither illustrates native dignity (per Frank), nor ridicules natives’ dignity (per Burke). But the opposite: the painting ridicules native dignity by showing Frank to be a myth, while illustrating natives’ dignity by showing Burke to be a clown.

But as Desmond Manderson reminds us, representation is only half the story. Art is never merely produced historically, to be read artefactually for the social discourses that have been layered in it. Art is itself productive. In Manderson’s terms, it has “presence,” and not just “meaning.”64 Paintings, like other works of art, might interact with audiences in ways that are affirmative, producing and reproducing the mythologies that enable a society to cohere, but a painting might also be critical—and arguably this is the way that art truly works, as art—by unsettling a society, by confronting it with its contradictions. As Manderson puts it, artworks are never “simply signs that mimic or represent other, specifically linguistic, things. Instead, they constitute, incarnate, or open up a space in which the spectator experiences a disturbance in their equilibrium. The encounter that takes place is not with a narrative or history, but with an event that cuts through time.” In this, an artwork is not just “the mimetic representation of the past,” but “the space of an event made present”—an “annunciation.”65 Exemplary here is the dramatic performance of Mullawirraburka and his fellow Kaurna, who turned mimesis into an event that shattered the colonists’ equilibrium. In response to Governor Gawler’s command—for the Kaurna to “imitate good white people,” to “become good British subjects”—the Kaurna did exactly that, but with a twist, turning the Governor’s official annunciation on its head with their own annunciation of sovereign authority. But to leave it at that would be to miss the point in Manderson’s argument, which is the temporal aspect of re-presentation, its repetition through time. It was this that the colonists feared most in the Kaurna’s performance: its repetition at corroborees across the country, causing the original performance to metastasise mythologically.66

The suggestion here is not that Native Dignity is somehow a re-presentation of the Kaurna performance, although it is very likely that Gill would have heard the stories of that day.67 The suggestion is simply that Native Dignity was touching the same colonial nerve. Just as Native Dignity uses the mimetic form of the pun to critical effect, creating non-identity between its title and its image in a way that denaturalises the concept of native dignity, Gill’s painting also uses mimesis in a way that creates non-identity between itself and its audience. Rather than word-play, it is distance that makes the difference here. Viewing Native Dignity alongside Homeward Bound again helps to see this. Looking first at Homeward Bound, one can see how it uses distance to uncritical effect. As a physical matter, the rural setting was fast becoming a distant experience for the urban European in the colonies who could afford to purchase a copy of The Australian Sketchbook; but even for those who lived rurally, the pastoral scene that Homeward Bound depicts would have operated more as a metonym for Mother Country than as a synonym for Indigenous Country, drawing the colonists who saw it “homeward” to Europe even as they gazed out over the yellow-flowering wattle. In this way, the picture distances its colonial audience from the singularities of the place in which they lived. At the same time, Homeward Bound creates a metaphysical distance by drawing its colonial audience, through the figure of the white pastoralist, into its tranquil golden valley, where, in a dreamy stupor, they might forget life in the colony and just imagine a gentle breeze, a muffled bleat, the soothing warmth of the setting sun. Both ways—physically, and metaphysically—the effect is settling: it settles colonisation by settling Europe in Australia, laying a European mythology of country over Indigenous country; and it settles the colonists’ mind by setting them at ease. As a result, not only is the country stolen twice-over, first in fact, second in myth, but the concept of native dignity—beautifully illustrated by the white pastoralist in his thread-bare coat—is left untroubled.

If Homeward Bound presents its colonial audience with a pacifying myth, then Native Dignity jolts them out of their stupor. It breaks down both physical and metaphysical distances: you are back on the colony’s city streets; and you are once more face-to-face with two Aboriginal people who not only refuse to just die away, but whose ongoing presence there puts lie to your own presence there. At the same time, Native Dignity uses humour to break down the distance between its colonial audience and their understanding of native dignity. Not only is the painting itself in the genre of a pun, but it also casts the Aboriginal couple as histrios, whose role, it will be remembered, is to represent society’s mythologies through burlesque. Gill’s European audiences in the Australian colonies are thus confronted with a truly grotesque scene—native dignity, performed in a public square—and the effect is unsettling. As Mikhail Bakhtin, scholar of the grotesque, has shown: “Everything that makes us laugh is close at hand, all comical creativity works in a zone of maximal proximity. Laughter has the remarkable power of making an object come up close, of drawing it into a zone of crude contact.”68 The metaphor Bakhtin uses is the stripping of sovereign authority: “Basically this is uncrowning, that is, removal of an object from the distanced plane.”69 On this new plane created by laughter, the object (“its hierarchical ornamentation removed”) is left exposed, vulnerable, ridiculous.70 If the object of Native Dignity is the European concept of “native dignity,” then the painting exposes it to ridicule before the very eyes of its colonial audience. See their contortion of features, their furious expression of face? It is the uncontrollable play of the social body’s histrionic muscles, innervated by the image.

Exhibition, Again

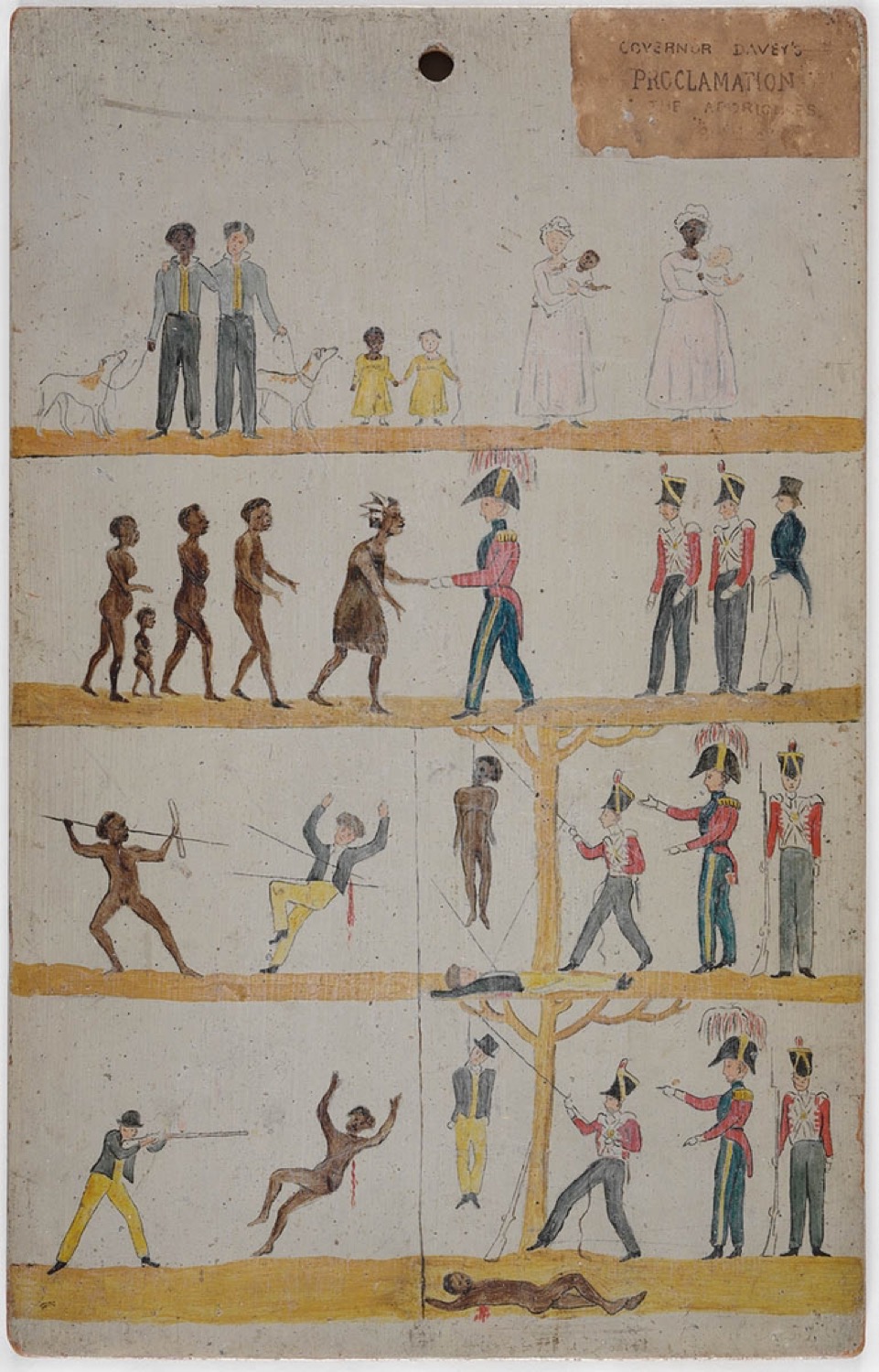

Native Dignity confronts its colonial audience with the contradictions that Homeward Bound paints over, unsettling the Pacific myth of Australia as a European home, along with the discourse of the universality of human dignity. But to see the painting’s unsettling effect in a more concrete way, let us turn to one last scene: the 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne. Native Dignity was not part of that Exhibition, although a dozen of Gill’s other watercolours were.71 Down the road from the Exhibition building, however, a lithographed version of Native Dignity would likely have been found on display in some shop-front.72 What was on display at the Intercolonial Exhibition was another, much more famous picture, Governor Arthur’s Proclamation to the Aboriginal People (fig. 4),73 a picture that, according to Manderson’s reading, is “one of the most significant statements of the rule of law in Australian colonial history.”74 Before it was rediscovered and put on display in lithographic form at the Intercolonial Exhibition,75 a hundred copies of the Proclamation had supposedly been circulated by the colonial government in early 1830s Tasmania, to instruct the Aboriginal people on the principles that constitute a so-called rule-of-law society.76

The Proclamation consists of four panels or frames, with the principle of “abstract equality” represented in the top frame.77 Here, eight European and Aboriginal people are coupled together—man and man, child and child, woman and woman, baby and baby—in such a way that the Aboriginal people appear to be perfect copies of their European counterparts, an appearance that is achieved by clothing the four pairs in identical European outfits and positioning them in mirrored postures.78 The effect is an imperial-mimetic work par excellence, a pictorial projection of the mythological “as if” identity that both drove the European civilising mission in the nineteenth century, and represented its end-point, its promise. This is the vision of colonists such as Gawler and Forster realised—the achievement of Civilisation down-under. As Manderson’s reading makes clear, this rule-of-law society, and the equality before the law that it promises, is not now, is “not yet.” It is a state that is to come once Aboriginal peoples become “civilised,” which is to say, once they have been remade in the image of European Man.79

In Governor Arthur’s Proclamation, the rule of law appears as a promise held in suspension until Aboriginal people reshape themselves to fit it. Nothing much has changed. The rule of law still holds out a promise of equality to be paid out only at that time when Aboriginal people become normal, and live in normal suburbs with normal jobs in a normal economy. Until those conditions obtain, equality is postponed and a state of exception invoked to justify measures of extraordinary severity and far-reaching implications, through which they will be bloody well made normal, and like it.80

Or as Governor Gawler put it in his own proclamation: “Black men! We wish to make you happy. But you cannot be happy unless you imitate good white men, build huts, wear clothes, work, and be useful.”81 To this official Proclamation, the picture of Native Dignity responds, like the legend of Mullawirraburka to the Cockatoo Governor, by drawing into focus its dehumanising work, its genocidal work. Both pictures—one seen from a dusty public square, the other from inside the imposing imperial Exhibition—represent the dignity of equality, but they could hardly have confronted their audiences with more opposed visions of it: on one side, equality as, and through, assimilation; on the other side, equality as, and through, an encounter of difference.82 And just as the colonial proclamations, whether oral or pictorial, were legal acts, directed at constituting the colonial-social order, so too were the responses, whether dramatised, narrated, or painted. Art and law are here “entwined and inseparable,”83 with the force of law dependent on the force of representation, and acts of representation being acts of law, colonial and otherwise.

-

This article is based on a longer study published as Shane Chalmers, “Native Dignity,” Griffith Law Review (2020): https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2020.1748833. It has benefited from the careful reading of two anonymous reviewers—to one I am indebted for suggesting the title, and to both for suggesting many important revisions. I also thank the editors of this special edition, Desmond Manderson and Ian McLean, for including the article in this wonderful volume of Index Journal, and to the general editors for creating the opportunity. ↩

-

John Thompson Dickson, The Science and Practice of Medicine in Relation to Mind: The Pathology of Nerve Centres and the Jurisprudence of Insanity (New York: Appleton, 1874), 86. ↩

-

See Keith Macrae Bowden, Samuel Thomas Gill: Artist (Hedges & Bell, 1971), 97. The Australasian noted in 1866, in a review of several of Gill’s “Colonial Comicalities,” including Native Dignity: “Mr S T Gill is a humourist as well as an artist, and has contributed sketches of considerable merit to the list of those which colonial art possesses. [ … ] His latest productions are perhaps the best he has yet produced.” Cited in Sasha Grishin, S T Gill and His Audiences (National Library of Australia, 2015), 212–216. ↩

-

Cf. Homi Bhabha, “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse,” October 28 (Spring, 1984): 125–33. ↩

-

On this colonial-utopian promise of the (“not yet”) rule of law, see Desmond Manderson, Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), ch. 3. ↩

-

See also Manderson, Danse Macabre, 179–182. ↩

-

See, e.g., Jeremy Waldron, Dignity, Rank, and Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). ↩

-

In this I take inspiration and instruction in particular from Desmond Manderson’s work on law and art, including most recently Manderson’s Danse Macabre and his edited collection, Law and the Visual: Representations, Technologies, and Critique (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018). On the everyday life of law, see Roderick A Macdonald, “Custom Made – for a Non-Chirographic Critical Legal Pluralism,” Canadian Journal of Law and Society, vol 26, no 2 (2011). ↩

-

Cited in John Blacket, History of South Australia: A Romantic and Successful Experiment in Colonization (Adelaide: Hussey & Gillingham, 1911), 145–146. ↩

-

James C Hawker, Early Experiences in South Australia (Adelaide: E S Wigg & Son, 1899), 8. ↩

-

John Wrathall Bull, Early Experiences of Life in South Australia and an Extrended Colonial History (Adelaide: E S Wigg & Son, 1884), 81–82 (italics added); see also Hawker, Early Experiences, 8. ↩

-

Hawker, Early Experiences, 8. ↩

-

Bull, Early Experiences, 84; see also Hawker, Early Experiences, 8–9; Blacket, History of South Australia, 145–146. ↩

-

Tom Gara, “The Life and Times of Mullawirraburka (‘King John’) of the Adelaide Tribe,” in History in Portraits: Biographies of Nineteenth Century South Australian Aboriginal People, ed Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus (Canberra: Aboriginal History Inc, 1998), 92-93. ↩

-

Bull, Early Experiences, 84. ↩

-

Bull, 84–85. ↩

-

Bull, 84–85. ↩

-

Hawker, Early Experiences, 9. ↩

-

Hawker, 8, citing Gawler’s speech to the “natives.” ↩

-

Adelaide Observer (Adelaide), 16 September 1843, 6. ↩

-

Adelaide Observer (Adelaide), 6. ↩

-

Robert Harrison, Colonial Sketches: or, Five Years in South Australia, with Hints to Capitalists and Emigrants (London: Hall, Virtue & Co, 1862), 76. ↩

-

See, e.g., Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 135–138. ↩

-

Adelaide Observer (Adelaide), 16 September 1843, 6. ↩

-

Geelong Advertiser (Geelong), 23 May 1846, 4. ↩

-

For a similar account of a “dramatisation of indigeneity before the law,” see the discussion of Kim Scott’s novel, That Deadman Dance, in Kathleen Birrell, Indigeneity: Before and Beyond the Law (London: Routledge, 2016), 207-209. ↩

-

Bull, Early Experiences, 8; see also Hawker, Early Experiences, 36. ↩

-

See, e.g., Hawker, Early Experiences, 5. ↩

-

Harrison, Colonial Sketches, 140. ↩

-

See Irene Watson, Looking at You, Looking at Me … Aboriginal Culture and History of the South-East (Burton: Irene Watson, 2002), 83-86; Irene Watson, “Naked Peoples: Rules and Regulations,” Law Text Culture, vol 4, no 1 (1998); Christobel Mattingley and Ken Hampton, eds, Survival in Our Own Land: “Aboriginal” Experiences in “South Australia” Since 1836, Told by Nungas and Others (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1988), 13–14. ↩

-

Cited in Mattingley and Hampton, Survival, 14. ↩

-

Mattingley and Hampton, Survival, 14. ↩

-

Grace Karskens, “Red Coat, Blue Jacket, Black Skin: Aboriginal Men and Clothing in Early New South Wales,” Aboriginal History, Vol. 35 (2011): 29. ↩

-

Karskens, “Red Coat, Blue Jacket, Black Skin, 29. ↩

-

Karskens, 5-6. ↩

-

Karskens, 1. ↩

-

B Arnold, “Three New Translations of German Settlers’ Accounts of the Australian Aborigines,” Torrens Valley Historical Journal, vol 33 (1988): 51. ↩

-

Arnold, “Three New Translations,” 51. ↩

-

Taplin cited in Mattingley and Hampton, Survival, 14. ↩

-

Karskens, “Red Coat,” 29. See also Watson, Looking at You, Looking at Me, 84. ↩

-

Cited in Karskens, “Red Coat,” 28. ↩

-

Having searched the Australian colonial newspaper archive from the 1830s to the 1880s, I found the term used frequently, and exclusively, in this way. ↩

-

Sentinel (Sydney), 15 October 1845, 4. ↩

-

Southern Argus (Goulburn), 25 November 1881, 2; see also Southern Argus (Goulburn), 20 June 1881, 2. ↩

-

See, e.g., Evening Journal (Adelaide), 1 May 1882, 3. ↩

-

See, e.g., Adelaide Observer (Adelaide), 5 July 1884, 46. ↩

-

Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong), 27 February 1880, 2. See also People’s Advocate and New South Wales Vindicator (Sydney), 28 February 1852, 6. This distinction, between the dignity of humans and the dignity of beasts, and the grounding of the former in the Biblical understanding that humans are made in the image of God, follows a long Christian tradition in Europe: see Brian Copenhaver, “Dignity, Vile Bodies, and Nakedness: Giovanni Pico and Giannozzo Manetti,” in Dignity: A History, ed Remy Debes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); Christopher McCrudden, “Human Dignity and Judicial Interpretation of Human Rights,” European Journal of International Law, vol 19, no 4 (2008): 657-660. ↩

-

See Mika LaVaque-Manty, “Universalizing Dignity in the Nineteenth Century,” in Dignity: A History, ed Remy Debes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 314-315; Michael J Meyer, “Kant’s Concept of Dignity and Modern Political Thought,” History of European Ideas, vol 8, no 3 (1987): 324-325. ↩

-

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men, Second Edition (London: J Johnson, 1790), 24. ↩

-

See also LaVaque-Manty, “Universalizing Dignity,” 314–315. ↩

-

See Edmund Burke, “Reflections on the Revolution in France,” in Reflections on the Revolution in France, ed Frank M Turner (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003 [1790]). ↩

-

See also Meyer, “Dignity,” 320–321. ↩

-

Cited in Meyer, 326. ↩

-

Meyer, 322. ↩

-

Burke, “Reflections,” 37. ↩

-

Meyer, “Dignity,” 322. ↩

-

Meyer, 322. ↩

-

Grishin, S T Gill, 216. ↩

-

Sentinel (Sydney), 15 October 1845, 4. ↩

-

Southern Argus (Goulburn), 25 November 1881, 2; see also Southern Argus (Goulburn), 20 June 1881, 2. ↩

-

Meyer, “Dignity,” 326. ↩

-

On the connection between the racist concept of “rationality” and the concept of human dignity, see Charles W Mills, “A Time for Dignity,” in Dignity: A History, ed Remy Debes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); Meyer, “Dignity,” 327–328. ↩

-

Adelaide Observer (Adelaide), 16 September 1843, 6. ↩

-

On this debate in art history, see Manderson, Danse Macabre, 179–182. ↩

-

Manderson, 181 (italics in original). On the “annunciative” work of art, see also “Foreword,” Manderson. ↩

-

Desmond Manderson, “The Metastases of Myth: Legal Images as Transitional Phenomena,” Law and Critique, Vol. 26 (2015). ↩

-

He also likely would have seen the painting of the event by Martha Berkeley, who was also present at the festival, titled The First Dinner Given to the Aborigines 1838 (1838). ↩

-

Mikhail M Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 23. ↩

-

Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination, 23. ↩

-

Bakhtin, 24. ↩

-

Intercolonial Exhibition: Official Catalogue, 107. ↩

-

A black and white lithograph of Native Dignity was printed in 1866 for sale in Melbourne by “DeGruchy & Leigh, 43, Elizabeth St.” ↩

-

Intercolonial Exhibition: Official Catalogue, 79. ↩

-

Desmond Manderson, “The Law of the Image and the Image of the Law: Colonial Representations of the Rule of Law,” New York Law School Law Review, vol 57 (2012). ↩

-

Penelope Edmonds, “Imperial Objects, Truths and Fictions: Reading Nineteenth-Century Australian Colonial Objects as Historical Sources,” in Penelope Edmonds and Samuel Furphy (eds), Rethinking Colonial Histories: New and Alternative Approaches (Melbourne: RMIT Publishing, 2006), 74. ↩

-

Manderson, “Colonial Representations,” 157. ↩

-

Manderson, 158. ↩

-

See Manderson, 158–159. ↩

-

See Manderson, Danse Macabre, ch. 3. ↩

-

Manderson, 100. ↩

-

Blacket, History of South Australia, 145–146. ↩

-

See also Manderson’s discussion of Benjamin Duterrau’s The Conciliation (1840) in Danse Macabre, 101–103. ↩

-

Manderson, 84. ↩

Shane Chalmers is a University of Melbourne McKenzie Postdoctoral Fellow with Melbourne Law School’s Institute for International Law and the Humanities (IILAH). He is author of Liberia and the Dialectic of Law: Critical Theory, Pluralism, and the Rule of Law (Routledge, 2018), and co-editor of the forthcoming Routledge Handbook of International Law and the Humanities.

shane.chalmers@unimelb.edu.au

Bibliography

- Arnold, B. “Three New Translations of German Settlers’ Accounts of the Australian Aborigines.” Torrens Valley Historical Journal 33 (1988): 48–56.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

- Bhabha, Homi. “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse.” October 28 (Spring, 1984): 125–33.

- Birrell, Kathleen. Indigeneity: Before and Beyond the Law. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Blacket, John. History of South Australia: A Romantic and Successful Experiment in Colonization. Adelaide: Hussey & Gillingham, 1911.

- Bowden, Keith Macrae. Samuel Thomas Gill: Artist. Maryborough, VIC: Hedges & Bell, 1971.

- Bull, John Wrathall. Early Experiences of Life in South Australia and an Extended Colonial History. Adelaide: E. S. Wigg & Son, 1884.

- Burke, Edmund. “Reflections on the Revolution in France.” In Reflections on the Revolution in France, edited by Frank M Turner. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003 [1790].

- Copenhaver, Brian. “Dignity, Vile Bodies, and Nakedness: Giovanni Pico and Giannozzo Manetti.” In Dignity: A History, edited by Remy Debes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. DOI http://10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0007.

- Dickson, J. T. The Science and Practice of Medicine in Relation to Mind: The Pathology of Nerve Centres and the Jurisprudence of Insanity. New York: Appleton, 1874.

- Edmonds, Penelope. “Imperial Objects, Truths and Fictions: Reading Nineteenth-Century Australian Colonial Objects as Historical Sources.” In Rethinking Colonial Histories: New and Alternative Approaches, edited by Penelope Edmonds and Samuel Furphy, 73–88. Melbourne: RMIT Publishing, 2006.

- Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

- Gara, Tom. “The Life and Times of Mullawirraburka (‘King John’) of the Adelaide Tribe.” In History in Portraits: Biographies of Nineteenth Century South Australian Aboriginal People, edited by Jane Simpson and Luise Hercus, 88–132. Canberra: Aboriginal History Inc, 1998.

- Grishin, Sasha. S T Gill and His Audiences. Canberra: National Library of Australia, 2015.

- Harrison, Robert. Colonial Sketches: Or, Five Years in South Australia, with Hints to Capitalists and Emigrants. London: Hall, Virtue & Co, 1862.

- Hawker, James C. Early Experiences in South Australia. Adelaide: E S Wigg & Son, 1899.

- Karskens, Grace. “Red Coat, Blue Jacket, Black Skin: Aboriginal Men and Clothing in Early New South Wales.” Aboriginal History 35 (2011): 1–36.

- LaVaque-Manty, Mika. “Universalizing Dignity in the Nineteenth Century.” In Dignity: A History, edited by Remy Debes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0015.

- Macdonald, Roderick A. “Custom Made – for a Non-Chirographic Critical Legal Pluralism.” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 26, no. 2 (2011).

- Manderson, Desmond. Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Manderson, Desmond (Ed.). Law and the Visual: Representations, Technologies, and Critique. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

- Manderson, Desmond. “The Metastases of Myth: Legal Images as Transitional Phenomena.” Law and Critique 26 (2015): 207–23.

- Manderson, Desmond. “The Law of the Image and the Image of the Law: Colonial Representations of the Rule of Law.” New York Law School Law Review, 57 (2012): 153–68.

- Mattingley, Christobel, and Ken Hampton, eds. Survival in Our Own Land: “Aboriginal” Experiences in “South Australia” since 1836, Told by Nungas and Others. Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1988.

- McCrudden, Christopher. “Human Dignity and Judicial Interpretation of Human Rights.” European Journal of International Law 19, no. 4 (2008): 655–724.

- Meyer, Michael J. “Kant’s Concept of Dignity and Modern Political Thought.” History of European Ideas 8, no. 3 (1987): 319–32.

- Mills, Charles W. “A Time for Dignity.” In Dignity: A History, edited by Remy Debes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. DOI http://10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199385997.003.0012.

- Waldron, Jeremy. Dignity, Rank, and Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Watson, Irene. Looking at You, Looking at Me … Aboriginal Culture and History of the South-East. Burton: Irene Watson, 2002.

- Watson, Irene. “Naked Peoples: Rules and Regulations.” Law Text Culture 4, no. 1 (1998): 1–17.

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Men, Second Edition. London: J. Johnson, 1790.