Guan Wei’s “Australerie” Ceramics and the Binary Bind of Identity Politics

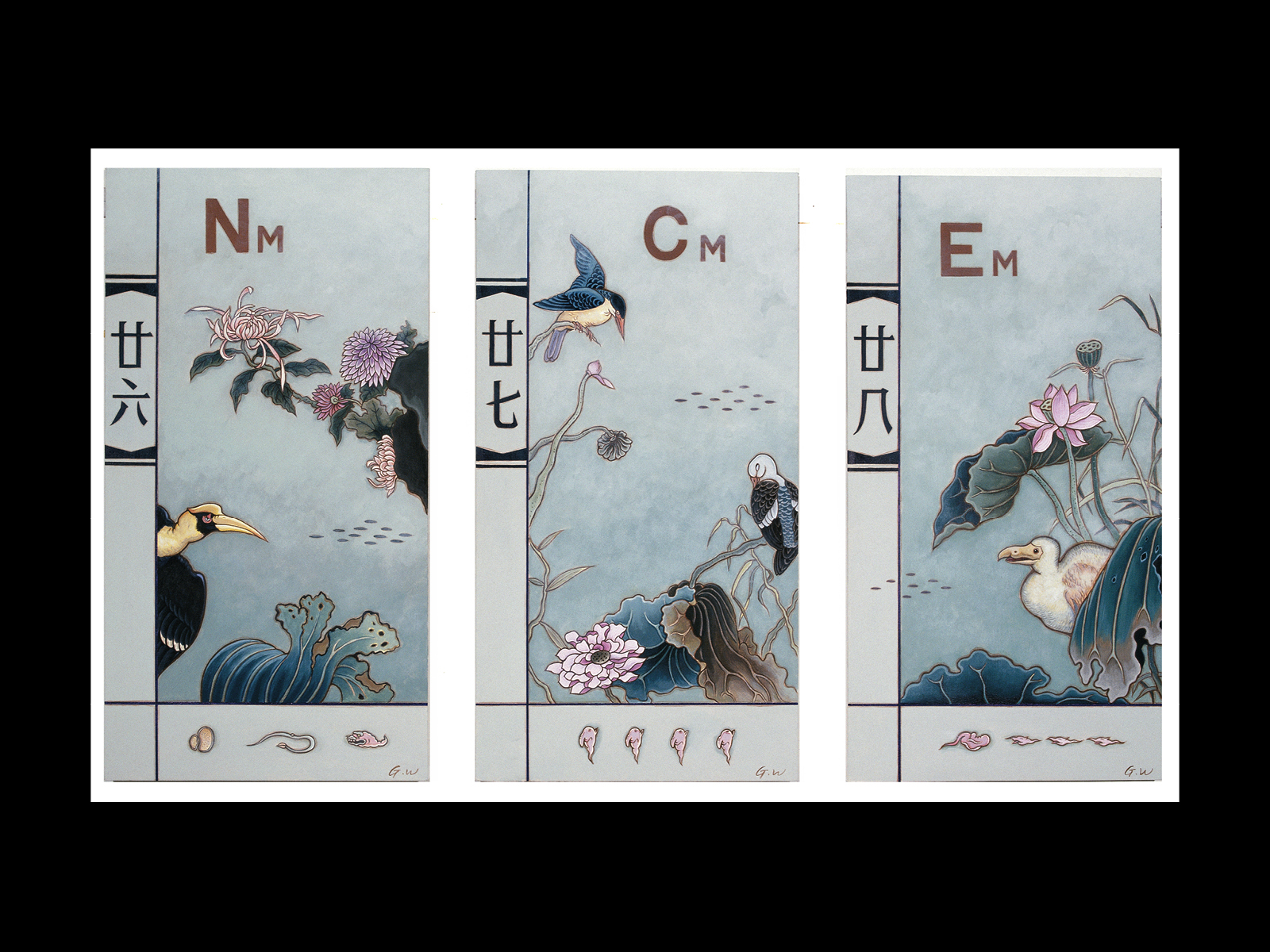

In October 2014, I visited Guan Wei’s studio to discuss the artist’s turn to porcelain following his journey earlier that year to Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, once China’s ‘Porcelain Capital’, to paint vases and dishes with a range of Aboriginal Australian-inspired motifs. To date, Guan Wei has created seven porcelain series in Jingdezhen: Subdued Demons (2012), To the Origin, Blue Like Sky, Extraordinary World, Land of the Dreaming, and Wonderland (all 2014). These have been shown in exhibitions in Australia and China, including dedicated displays at Arc One Gallery, Melbourne (2014); Martin Browne Contemporary, Sydney (2015); and Red Gate Gallery, Beijing (2018).1 Although significant for their quantity and their transposition of his signature style to a new medium, neither Guan Wei’s ceramics nor his adaptation of Aboriginal Australian-inspired motifs in these and earlier works have received substantial critical attention. As the most prominent representative of the ‘post-Tiananmen generation’ of Chinese émigrés who arrived in Australia after 1989, the reception of his art has instead been consistently tied to a multiculturalist identity politics that foregrounds his combination of Chinese and Australian/European iconographies. His otherworldly figures adrift in dense spaces of iconographic collision have inspired endless meditations on the migrant experience and are regularly used to illustrate Chinese-Australian ties. By 2003, the literature inspired by his work and consistent with this trend had become so unwieldy that Louisa Teo lamented “a certain predictability” in an artistic practice “so extensively written about that it is ... difficult to offer fresh perspectives.”2

As a case-study in the artist’s infrequently acknowledged use of Aboriginal Australian-inspired motifs, Guan Wei’s ceramics provide one such fresh perspective, creating an idiosyncratic and even exotic vision of Australia in which White Australians are either entirely absent or appear as malign intruders.3 Like the eighteenth-century fashion for Chinoiserie once inspired by the porcelain manufactured in Jingdezhen for global export, this “Australerie” aesthetic creates a vision of cross-cultural exchange that blurs fact and fiction, Orient and Occident. Rather than simply reversing the terms of the latter binary by privileging East over West, however, Guan Wei has displaced the “Western” subject in a vision of Australia entirely of his own making. This vision has roots in his previous work, yet it too has received little attention relative to his fusion of Chinese and European iconographies, or his imaging of migrant identity. Turning away from the East-West binary of a multiculturalist identity politics, his Australerie uncovers a less well-known site of imaginative encounter between different peoples and cultures.

Chinoiserie, Aboriginalia, and the subversive act of conceiving otherwise

There are two key interpretive models that distinguish Guan Wei’s Australerie by reinforcing its resonance with the aesthetics of the exotic. The first is a comparison drawn by sinologist Geremie Barmé between his fascination with otherness and “the codified appreciation of ... rarities, oddities, fascinations, artifices and ephemera” in wunderkammern, or cabinets-of-curiosity.4 The second is curator Natalie King’s comparison of his deliberately obscurantist compositions with the architectural folly—”an absurd structure [that] connotes delight, terror and ecstasy.”5 For both critics, it is Guan Wei’s creation of an alternate world that imbues his art with such mystery, compelling a recognition of unexplored spheres of the imagination. For Victor Segalen (1878-1919), an early Sinologist and scholar of exoticism, this recognition constitutes a definitive trait of the exotic,

which is nothing other than the notion of difference, the perception of Diversity [sic], the knowledge that something is other than one’s self ... nothing other than the ability to conceive otherwise.6

Guan Wei demonstrates his “ability to conceive otherwise” throughout his oeuvre, though it is especially apparent in his ceramics. The composite creatures, fragments of narrative, and parodies of rationalist symbolic codes that adorn his plates and vessels conjure visions of another world, painstakingly replicated in miniature. And like a cabinet-of-curiosity, or a folly in an Anglo-Chinese garden, this world is dependent on one man’s idiosyncratic fascination.

In Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fables for a Contemporary World (2006–7), the exhibition that inspired Barmé to associate Guan Wei’s work with the wunderkammer, the artist proposed an alternative history in which Australia was “discovered” by Ming-dynasty admiral Zheng He (d. 1433). Although the installation did not feature any ceramics of Guan Wei’s making, it did include nineteen ceramic vessels and a group of ceramic fragments from the collection of Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. This highlighted the artist’s recognition of the important role that ceramics played in the history of global exchange. Guan Wei recalled this history in our conversation in 2014, explaining that one of the qualities of porcelain he found most inspiring is its transmission of “cultural codes.”7 He also drew a comparison between his ceramics and the exhibition’s playful revisions of history, speculating that they might inspire theories of Chinese-Aboriginal interaction if discovered by archaeologists in the distant future.8 Alongside wunderkammer and Anglo-Chinese follies, a third interpretive model for his Australerie can therefore be proposed that both foregrounds and subverts the dynamic of exchange: the visions of an exotic other inspired by eighteenth-century Chinoiserie.

The historiography of Chinoiserie is amply covered by the literature devoted to this subject.9 Against the canonical narrative and the understanding it has promoted, however, prominent historian David Porter has recently sought to redefine the style as an antidote to stereotype and convention even, paradoxically, as it endorsed fantasies of a mysterious Orient capable of inspiring both awe and absurdity. In contrast to the “classical taste and polite bourgeois culture” of eighteenth-century England, Porter argues that Chinoiserie promoted

a celebration of surface splendour ... [and a] mirage of visual delights that could only deceive and lead the viewer astray ... [resisting] any essentialising impulse [and] revealing an essence that is itself a pastiche, a guiding principle not of purity and integrity but of thorough-going mongrelisation.10

Porter goes on to explain that this guiding principle was an ideal vehicle for an “experimental self-fashioning” founded not on preordained inheritance or immutable essence, but “cultural permutation, plurality, [and] an aesthetic subject cut loose from naturalised hierarchies.”11 In a similar manner, Guan Wei’s Australerie ceramics resist the persistent tendency to reduce his work to an expression of an essentialised Chineseness for White Australian viewers, giving precedence instead to an iconographic vocabulary in which the authority that these viewers conventionally enjoy is displaced by a recognition of more pluralistic cultural realities. At the same time, the application of this vocabulary to the historically “exotic” medium of porcelain amplifies its allure and appropriates a vision of China as a land of blue-and-white pagodas to Guan Wei’s own vision of Australia as the ancient and earthy “Land of the Dreaming”.

Guan Wei’s application of Chinoiserie to an Australian context also highlights its kitsch appeal, provoking comparison with a category of material culture generally termed “Aboriginalia.” For Porter, the gaudiness of Chinoiserie objects is essential to their subversive implications. In opposition to the canon of classical taste, these objects convey

a bold celebration of disorder and meaninglessness, of artifice and profusion, an exuberant surrender to all that remains unassimilated by ... classical symmetries ... that prizes irreverent laughter ... and that revels in the playfully anarchic fantasies of an unintelligible world.12

The unruly fascination inspired by Chinoiserie objects undermined the harmonious symmetry, proportion and moral rectitude of the social order endorsed by classical aesthetics. Even more subversive, however, was the blurring of formerly rigid boundaries between polite and vulgar society brought about by the democratic availability of this taste for the exotic. As ersatz artefacts of an ancient empire, Chinoiserie objects inherited some of the cultural authority once associated with European reverence for China, but their collection by members of the aspirational middle classes simultaneously propelled these visions into a “brave new world of commerce and fashion.”13 It was this “dual status ... as both legitimate art and fashionable commodity,” Porter asserts, that gave Chinoiserie its greatest potential for subversion.14

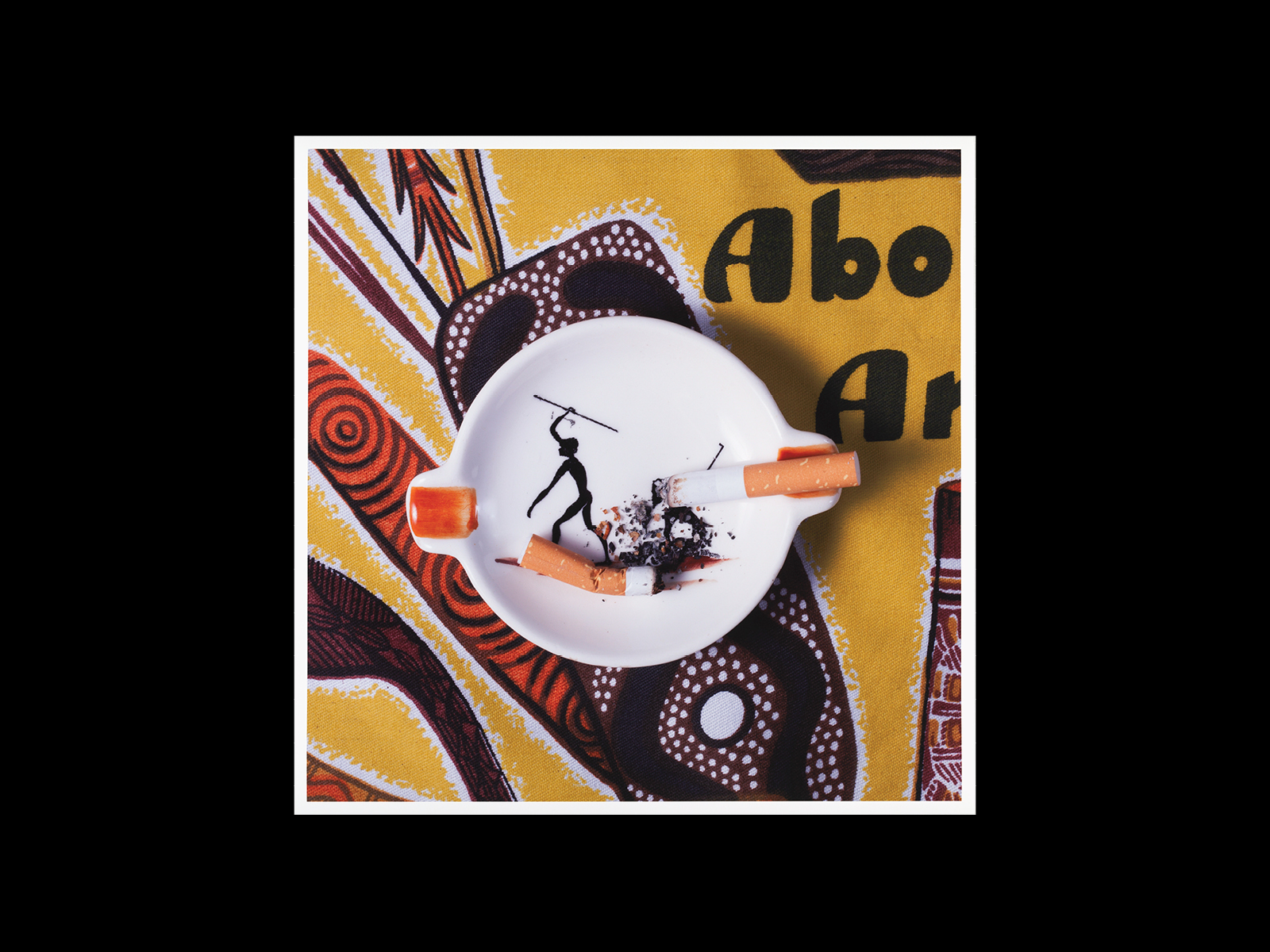

A comparable blurring of the authentic and ersatz underlies the significance of Aboriginalia, defined most clearly by sociologist Adrian Franklin as a uniquely Australian category of:

decorative objects depicting Aboriginal peoples and/or culture and motifs that were predominantly designed for, sold to and produced by non-Aboriginal Australians ... as “the look” and the truly authenticating expression of what was properly Australian.15

Franklin traces the desire for such objects to the post-Federation search for national emblems, yet a fascination with Aboriginality and the marketing of souvenirs to appeal to this fascination have been present since first contact.16 The colonial view of Aboriginal people as “pests, sometimes comic, sometimes vicious, but always ... in the way of a civilised Australian community,” excluded them from early expressions of this search, which favoured animal and floral motifs.17 From the 1920s, however, interest in Aboriginal culture among modernist artists and designers created a public taste for such imagery. This was soon satiated by ceramics manufacturers including Martin Boyd, Essexware, and Gunda Potteries, who took the lead in the commercialisation of Aboriginal-inspired motifs.18

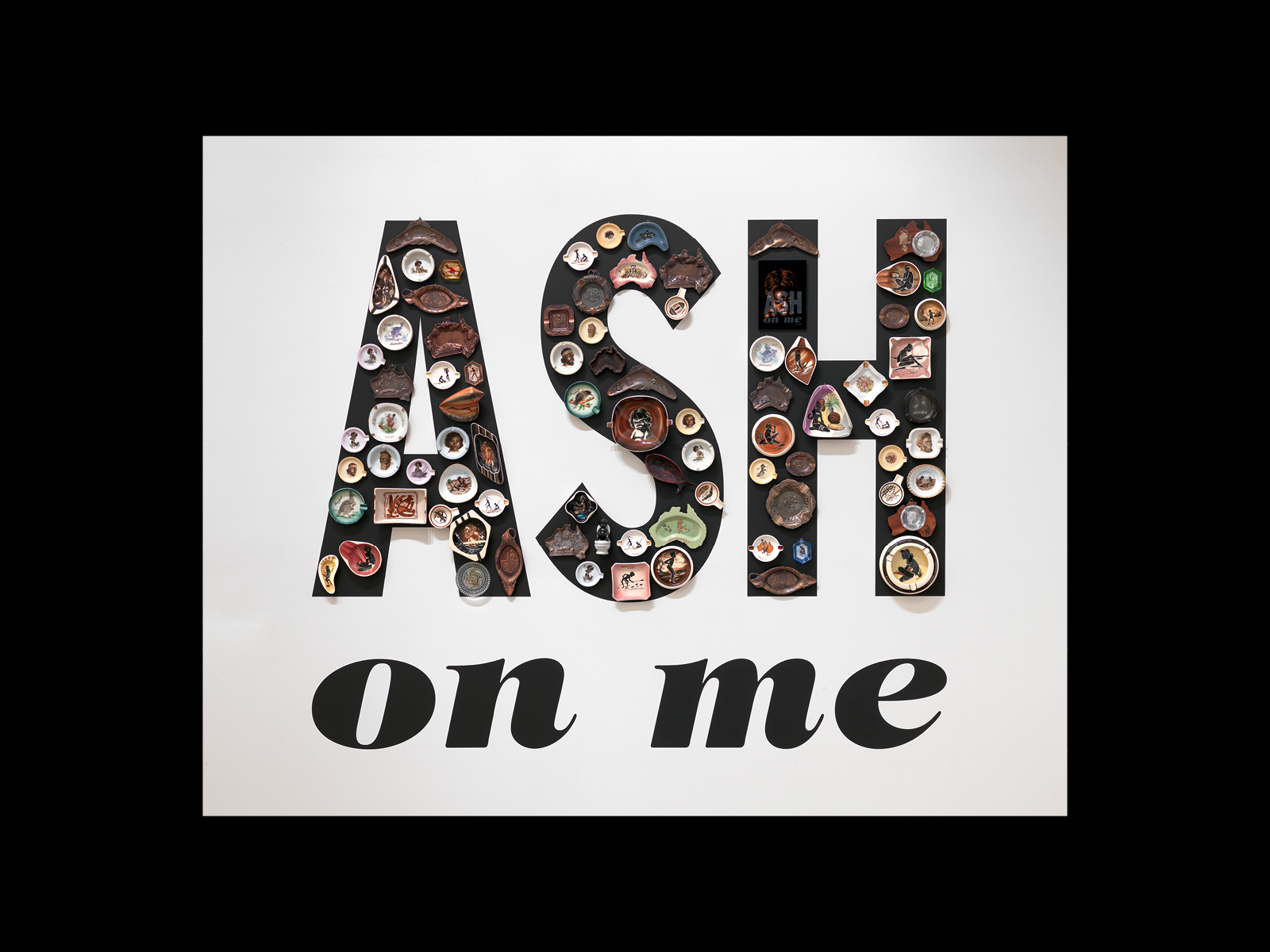

Guan Wei’s ceramics could be viewed as descendants of these mid-century expressions of settler primitivism, yet he can also be positioned alongside contemporary artists, such as Tony Albert, who have appropriated Aboriginalia to critique the politics of racial representation.19 Albert and other artists found inspiration amid the resurgent nationalism of the 1990s, when Aboriginalia came to express the “new pluralist and progressive characterisations of the nation.”20 Nevertheless, despite different intentions, its defining traits remained consistent: ochre and natural tones; cross-hatching, dotting and other desert painting techniques; the appropriation from lithic art of handprint and “x-ray” motifs; and adaptation of boomerangs, didgeridoos and similar objects of Aboriginal material culture. Albert’s use of Aboriginalia in ASH on me (2008; fig. 1) and his “Mid Century Modern” series (2016; fig. 2) foregrounds this continuity. He has often repeated the story of his fascination as a continuous movement from appreciation to activism:

My collection of Aboriginalia started as a young child and ... stemmed from something very innocent. I genuinely loved the ... imagery, particularly the faces, which reminded me of my family. When I was in high school, I became much more aware of Indigenous issues [and] discovered the work of contemporary Aboriginal artists such as Tracey Moffatt and Gordon Bennett [who] forced me to look at these objects in a new light.21

Albert’s explanation exposes the potential for subversion within such objects. Despite their use of degrading stereotypes, the familiar homeliness of ashtrays, cups and saucers, and other ephemera adorned with Aboriginal-inspired motifs opens them to unintended identifications, fusing ridicule with affection, prejudice with fond memories of family and childhood. Through sheer quantity, Aboriginalia therefore ensured that Aboriginal faces remained a persistent presence in the nation’s self-image and the lives of its people, even while the White Australia Policy (1901-66) endorsed their systematic disenfranchisement.

Multiculturalist readings of Guan Wei’s art and their political-historical context

At the intersection of Aboriginalia and Chinoiserie, Guan Wei’s Australerie ceramics expose the stereotypes that structure Australian understandings of cultural identity. A review of the writing inspired by his oeuvre, however, reveals a preference for two interpretive viewpoints that focus instead on his relevance for mainstream multicultural identity politics. The most persistent of these, symptomatic of the political climate in which he gained recognition, casts the artist as an interlocutor for his heritage and his art as a gateway to Chinese culture, while the second shifts focus to his experiences as a migrant. Guan Wei is reduced in both cases to “a genial door guardian … who [can] explain the stories of one world to the other.”22 These perspectives obscure his Australerie by forcing his work to conform with the binary politics of inclusion and exclusion that define the White Australian national space.

This space has developed in several phases since Federation, tied to continuous moments in a process of national self-imaging. Yet a consistent emphasis has endured through all stages of development on what anthropologist Ghassan Hage terms the “White Nation fantasy”:

[a] belief in [the] centrality [of White Australians] as enactors of the Law in Australia or, to put it differently, as “governors” of the nation ... [and] of ethnics [sic] as people one can make decisions about: objects to be governed.23

As expressions of this belief, “White racism” and “White multiculturalism” are not opposed: “it is not simply a divide between good, tolerant people and bad, intolerant people,” Hage explains, but rather “a difference [in] capacity of tolerance between people who equally claim ... to manage national space.”24 Both are effects of “White paranoia”: anxiety among White Australians that irrepressible cultural forces will dissolve their self-given right to decide the limits of national inclusion. Hage identifies Aboriginal genocide and isolation from Europe as two sources for this paranoia, the former imposing “a constant reminder of the uglier aspects of the colonial past” while the latter intensifies “a fear of being swamped by [a] hostile and uncivilised otherness.”25 When these points of tension meet, and especially when they meet outside the White Australian national space, an unsettling subversion is inevitable.

To understand how multiculturalist readings of Guan Wei’s art arise from such attitudes, it is necessary first to outline the political historical context for multiculturalism in Australia. The conventional narrative is coloured by what Hage has termed a “then we were nasty, now we are nice” polarity, defining enlightened multiculturalism as the binary opposite of the White Australia policy.26 However, political scientist James Jupp, a leader of the debates surrounding this topic since the publication of his decisive Arrivals and Departures (1966), has consistently shown that the legacy of White Australia and later policies of assimilation and integration remain central to understandings of Australian multiculturalism.27 Hage dates the shift from integration to multiculturalism to the efforts of Gough Whitlam (Prime Minister 1972-5) and his Immigration Minister Al Grassby, who promoted cultural diversity as an inescapable fact (“descriptive multiculturalism”) and a desirable situation (prescriptive multiculturalism”).28 In 1978, Malcolm Fraser (Prime Minister 1975-83) further endorsed this shift from integrationist policy when he appointed Frank Galbally to oversee the “Migrant Services and Programs” report that established foundational multiculturalist tenets of equal opportunity, eradication of racial prejudice, promotion of cross-cultural understanding, and the institution of migrant support services.29 In the 1980s, however, bipartisan consensus began to dissolve, revealing the persistent influence of White Paranoia and prompting Bob Hawke (Prime Minister 1983-91) to commission the “National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia: Sharing Our Future” (1989).30 Although consistent with earlier policies, Hawke’s agenda initiated a crucial shift away from programs that aimed to integrate migrants within the national space, toward a recognition that the nation itself had been transformed by migration.31

Chinese émigré artists arrived in Australia at the height of the Multiculturalist debate in the 1990s and were soon incorporated within its polarising terms. John Howard (Prime Minister 1996-2007) broke from political convention by declaring support for race-based immigration, while the rise of far-right politician Pauline Hanson incited further racial prejudice. For Howard and Hanson, Hawke’s vision of a multicultural Australia was profoundly unsettling, “reviving in their minds the paranoid fears of cultural extinction” that had inspired the White Australia Policy (1901-66). For those who “wished to shed the image of Australia as a racist colonial backwater,” on the other hand, multiculturalism held great appeal.32 In the art-world, these divisions were given voice in the “Asianisation” debate sparked by a shift in curatorial and art-critical focus from Europe and North America to the Asia-Pacific.33 Supporters heralded Asian artists as harbingers of a new national direction, citing their success as a case of successful integration: “what better argument against the claim that Australia is being ‘swamped by Asians’ than ... an Asian-Australian artist who ... has made a remarkable contribution to Australian art?”34 Journalist Nikki Barrowclough, for example, trumpeted the arrival of a “new wave of Chinese ... writers, artists, academics, actors and filmmakers [who] will have an impact on Australia’s cultural life as, in turn, they will be influenced by the Australian lifestyle,” while art critic John McDonald argued that “post-Tiananmen exiles” were “changing the face of Australian art.”35 Writing at the peak of the debate, Barrowclough and McDonald endorsed several critical tendencies that gained lasting authority.

The first of these is the celebration of émigrés as transformative but ultimately integrated contributors to Australian cultural life, reducing artists to one of two roles: “a model minority [or] voiceless and consigned to an invisible migrant ghetto.”36 As such, their life in Australia is reduced to a narrative of struggle, hard-won acceptance, and enjoyment of the fruits of success. Marita Bullock has identified this narrative in writings on Ah Xian, whose journey to Australia paralleled Guan Wei’s.37 The reception of both artists’ work has been marked by a tendency to assimilate idiosyncratic qualities within a readymade narrative or, if they prove unassimilable, like Guan Wei’s fascination with Aboriginal Australia, to relegate them to the obscurity of critical inattention.38

Another trait of multiculturalist interpretation is a recurring emphasis on Chineseness. Bullock also identified this in her discussion of Ah Xian, associating it with a desire to “contain the unsettled and the unsettling – to sort out difference” by packaging cultural identity for easy consumption.39 The same desire to package difference appears in writings on Guan Wei, many of which praise “his deeply inscribed traditional sensibilities” and elaborate the biographic focus of the refugee-to-celebrity narrative, highlighting his descent “from a noble ... Manchu family” with ties to the imperial clan.40 This illustrious genealogy is usually followed by a comparison of his art with Chinese literati painting: the scroll- or screen-like verticality of his canvases; the early restriction of his palette to black, white and red; and the “strong graphic sensibility” he applies to “dream-like spaces” that have been compared with the passages of atmospheric negative space characteristic of landscape paintings in ink.41 Rather than situate Guan Wei’s art in a coherent artistic lineage, such points of comparison serve primarily to mark him as culturally different for a White Australian audience.

Guan Wei’s works have also been repeatedly positioned as case-studies in diasporic hybridity, defined by postcolonial scholar Homi Bhabha as a “contradictory and ambivalent [third] space” outside the borders of the nation-state.42 This potentially liberating recognition of cultural fluidity, however, risks simplification “as a ... catch-all term that fails to adequately consider ... diverse models and experiences,’ a reductive marker of difference packaged for ready consumption.43 Guan Wei, for example, has been described in attractive but ambiguous terms as “a juggler of systems, images [and] traditions” at “the threshold between two worlds,” who, “like a cultural tourist, moves across the globe absorbing various influences.”44 His art has been read as an expression of “the migrant artist’s special vocabulary of old and new, private and public, East and West,” offering an insider’s perspective into “global spaces of displacement.”45 Although evocations of hybridity complicate stereotypes of Chineseness, the third space to which they refer is too ambivalent and can become equally reductive, confining the complex aesthetic play of Guan Wei’s work to a convenient case-study in the benefits of multiculturalism.

Guan Wei’s engagement with Aboriginal Australia

Against this dominant paradigm, I propose a critical model that recognises the artist as an individual whose inspirations and preoccupations exceed a reductive identity politics. Rather than searching for traces of Chineseness or migrant identity, I contend that a more nuanced understanding of Guan Wei’s artistic vision can be gained by studying his engagement with Aboriginal Australian art. This shift in focus initiates a parallel shift away from the binaries of East and West, inclusion and exclusion, toward a personal perspective influenced—but not defined by—cultural heritage. Fascination with Aboriginal Australia has been a recurring trope in Guan Wei’s oeuvre almost since his arrival in this country but has rarely been discussed by historians and critics. Although the expression of this Australerie in his ceramics is the primary subject of this paper, it is therefore worthwhile to trace how Aboriginal-inspired motifs have emerged in his work over the last three decades.

Guan Wei has long expressed a fascination for Australia as a continent defined by geographic vastness, an unforgiving climate, and primeval antiquity. He recalls an exhibition of Australian landscapes on loan to the National Art Museum of China and a screening of Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) in the early 1980s as formative touchstones for his impressions of this “wild and different ... extraordinary [country].”46 After arriving in Australia almost a decade later, Guan Wei confided to the writer Ouyang Yu:

I found things new and strange and I was curious ... I found it very interesting and [sought] a deeper understanding of their culture, particularly its history, geography, and its Aboriginal things.47

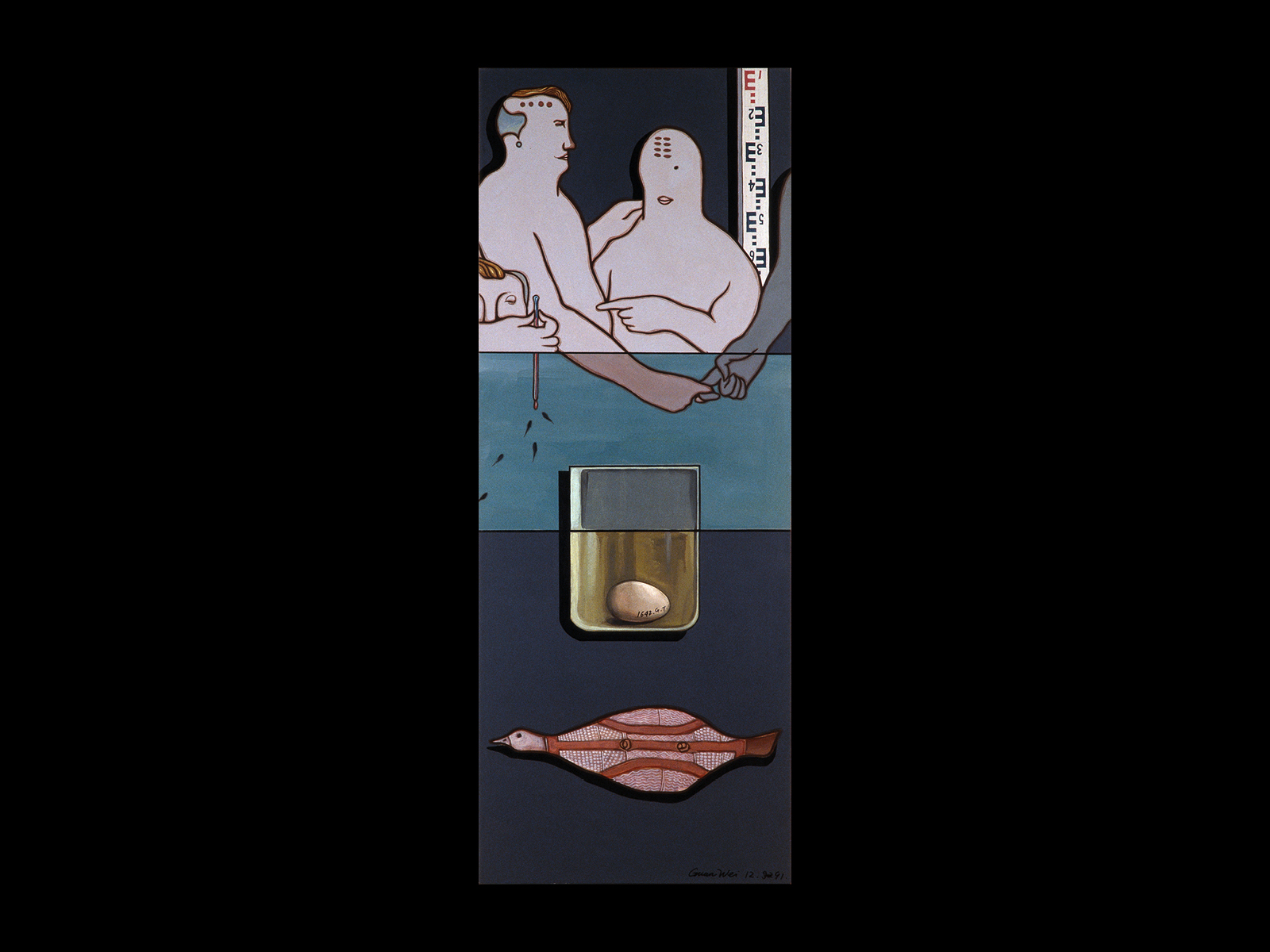

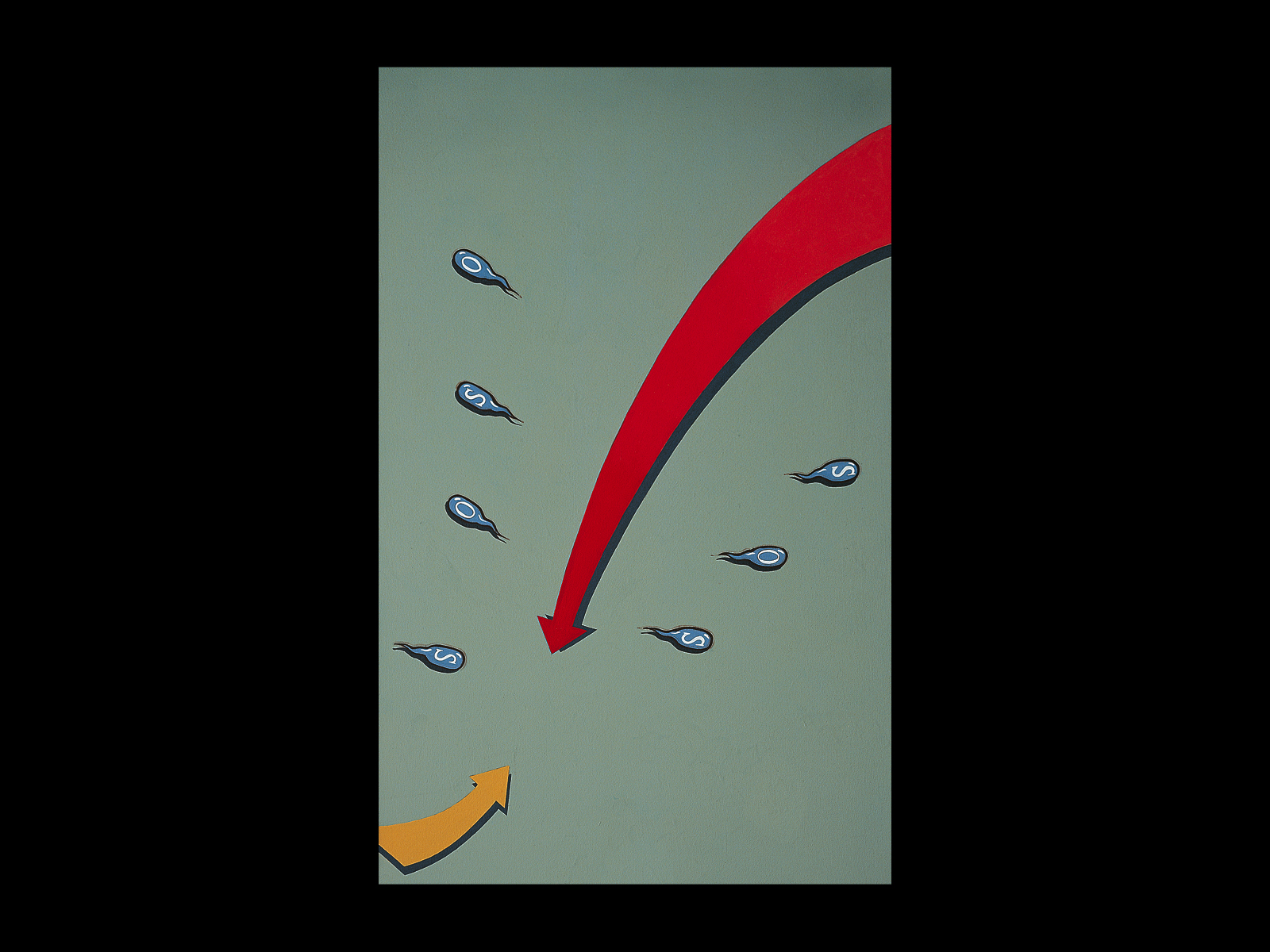

These sentiments were expressed in his first significant Australian body of work: the Living Specimen (1992) series of acrylic paintings on canvas. Although generally characterised by a juxtaposition of Chinese and European motifs, one canvas in the series presents an Aboriginal Australian-inspired duck hovering below an unhatched egg preserved in a beaker, perhaps to contrast an earthy authenticity with a lifeless specimen of scientific study (fig. 3).48 The watery blues throughout the series have also been cited as an expression of the new awareness of “coastline, water and distance” that Guan Wei gained in Tasmania, “an island ... in a vast ocean of nothingness.”49 Even at this stage in his career, the qualities of his Australerie were starting to appear: the wonder of open spaces, the mystic isolation of ocean solitude, and the coveted authenticity of Aboriginal flora and fauna.

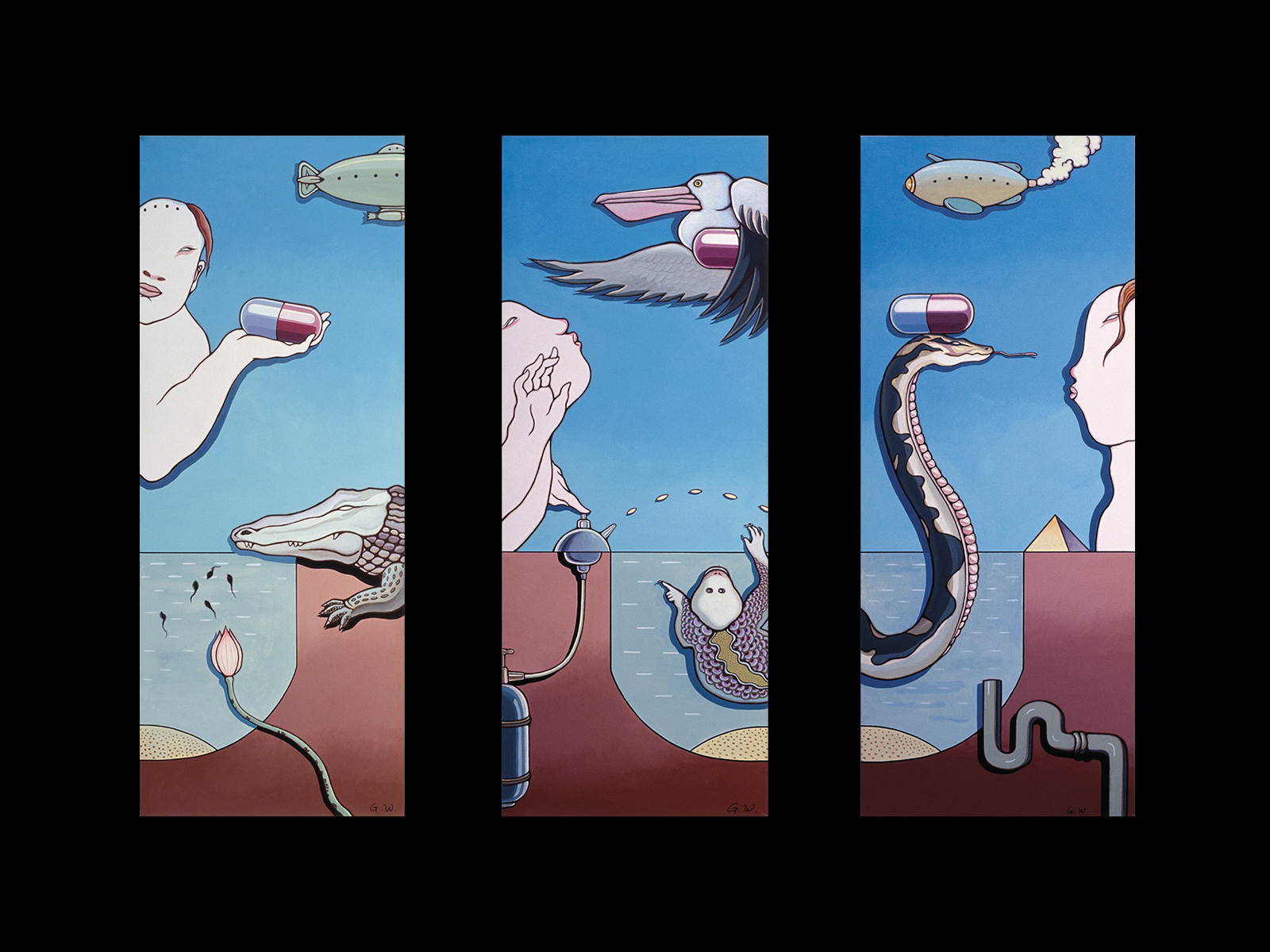

Guan Wei further elaborated these tenets in Treasure Hunt (1995) and Exotic Flowers and Rare Grasses (2001), again emphasising the landscape and its inhabitants. Treasure Hunt marked a departure from his previously muted palette for vivid blue and red-brown tones that recall the hues of the desert, and a brightness that emulates the “brilliant intensity” of a cloudless sky.50 These sunburnt desert scenes are imbued with additional local familiarity by a familiar cast of lizards, kangaroos, crocodiles, snakes, platypuses, and other Australian fauna, juxtaposed again with products of machine technology (fig. 4). Each painting narrates an episode in the pursuit of a pill-like capsule that remains out of reach, an analogy perhaps for Guan Wei’s desire to capture the elusive essence of the continent and his belief that this could provide an elixir for his curiosity. The desire to classify is also central to Exotic Flowers and Rare Grasses, a series of pseudo-botanical illustrations of fictional plants fusing Chinese and Australian flora (fig. 5), each ascribed medical properties in code at the bottom of the canvas. Like the capsule in Treasure Hunt, however, these hybrid specimens are unattainable products of an unknown climate that exists only in the artist’s imagination.

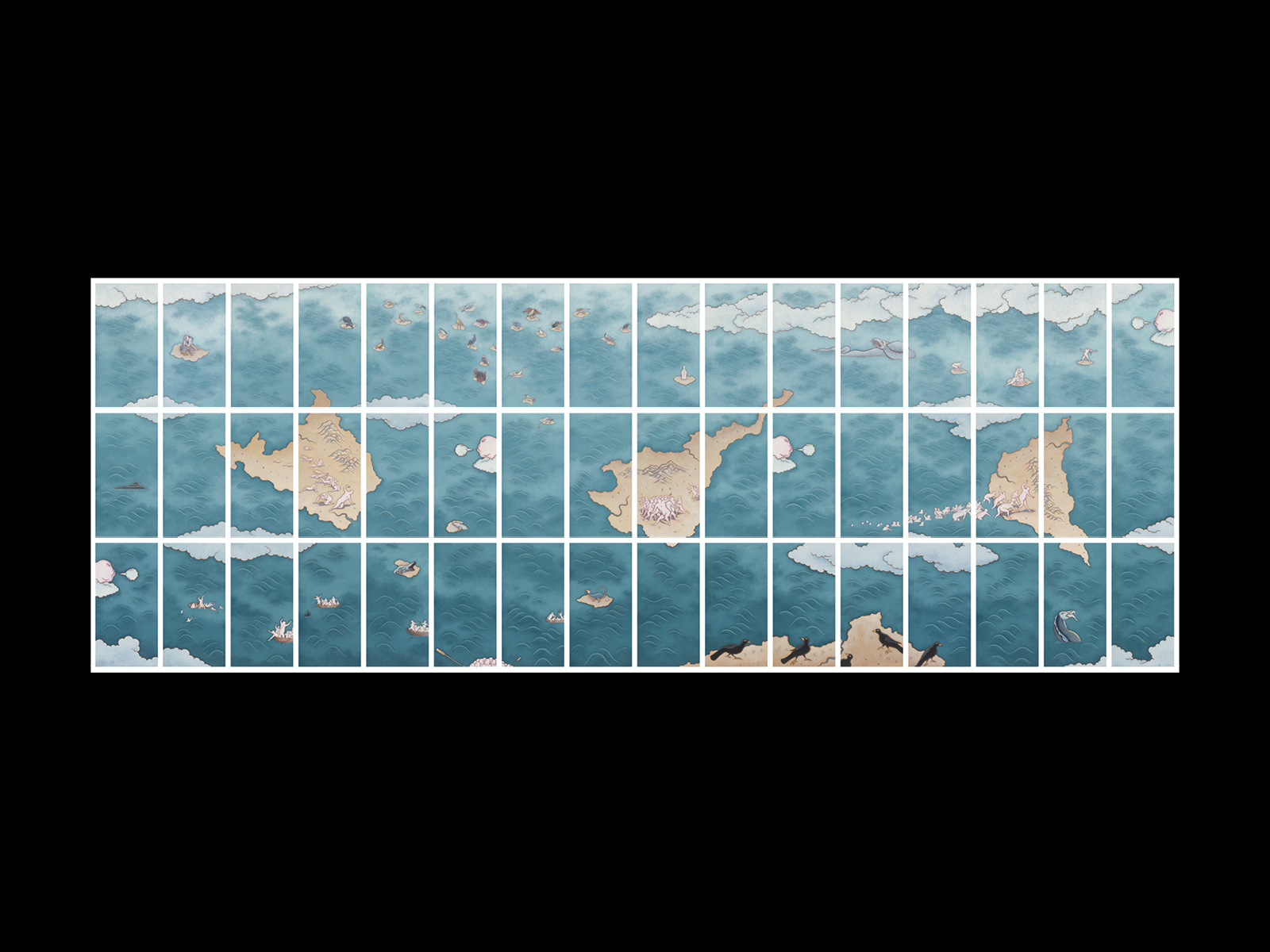

Guan Wei’s attempts to map this climate have found their most encyclopaedic expression in his cartographic representations of fictional though vaguely familiar continents. In Island (2001; fig. 6) and Dow: Island (2002; fig. 7) crocodiles, emus and other antipodean creatures traverse a fractured archipelago, their optimism in the face of aridity intended to reflect “[the] environment of Australia [and] the Australian spirit.”51 Guan Wei’s evocative labelling of the landmasses in Dow: Island— “The Enchanted Coast,” “Trepidation,” “Aspiration,” and so on—prompted many to associate both works with asylum seekers.52 Yet they can also be read as essays in the imagining of another Australia: an exotic island nation adrift in a vast, impossibly blue ocean, teeming with strange, composite creatures.

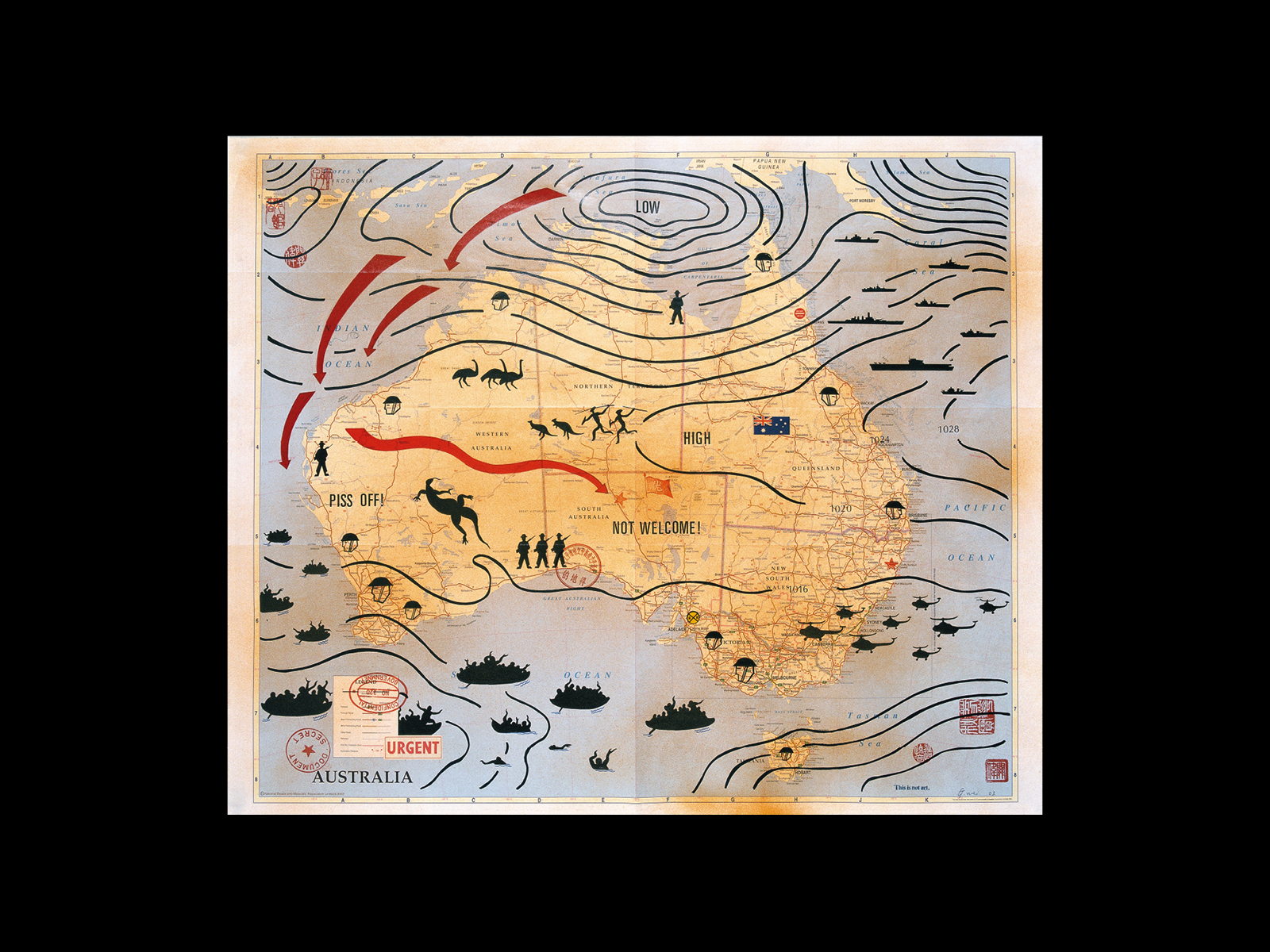

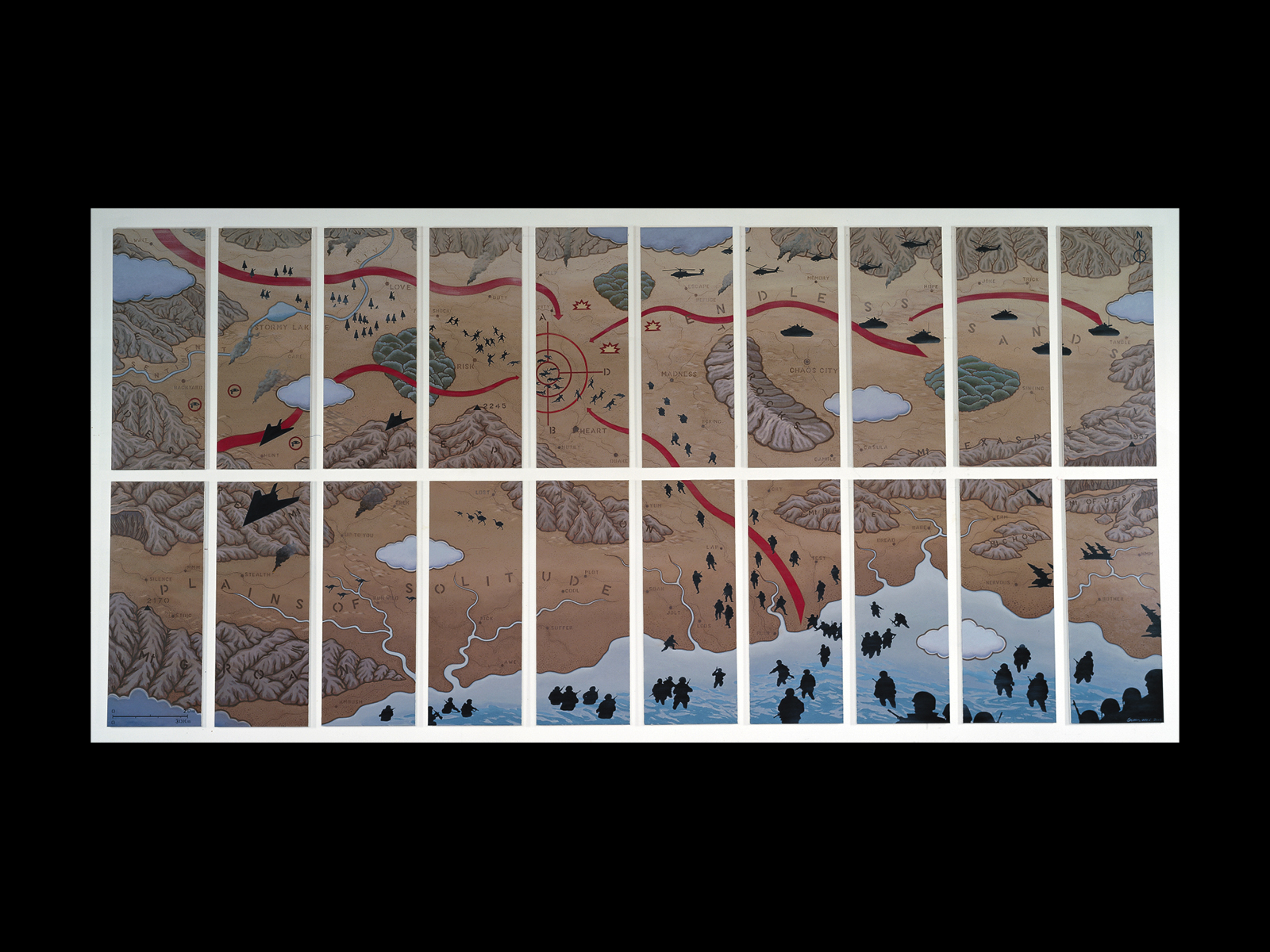

It is also in Guan Wei’s cartographic canvases that Aboriginal figures enter his oeuvre as black silhouettes, running, dancing and hunting. In Trepidation Continent (2003; fig. 8)—one of many works with militaristic overtones that critics have associated with Howard’s draconian immigration policies—two men brandish spears and small shields at the centre of a map of Australia. They are shown chasing a pair of kangaroos, oblivious to the battalions of soldiers, disembodied sentinels, warships bristling with guns, helicopters, and boats overflowing with human cargo that surround them. Similar figures appear in Target (2004; fig. 9), engaged in bitter conflict with invading soldiers, helicopters, tanks and fighter jets on a landmass boldly emblazoned with doom-laden place names. This painting introduces another aspect of Guan Wei’s Australerie: the shock of encounter, staged here as an eruption of colonising forces into a continent of Edenic bliss.

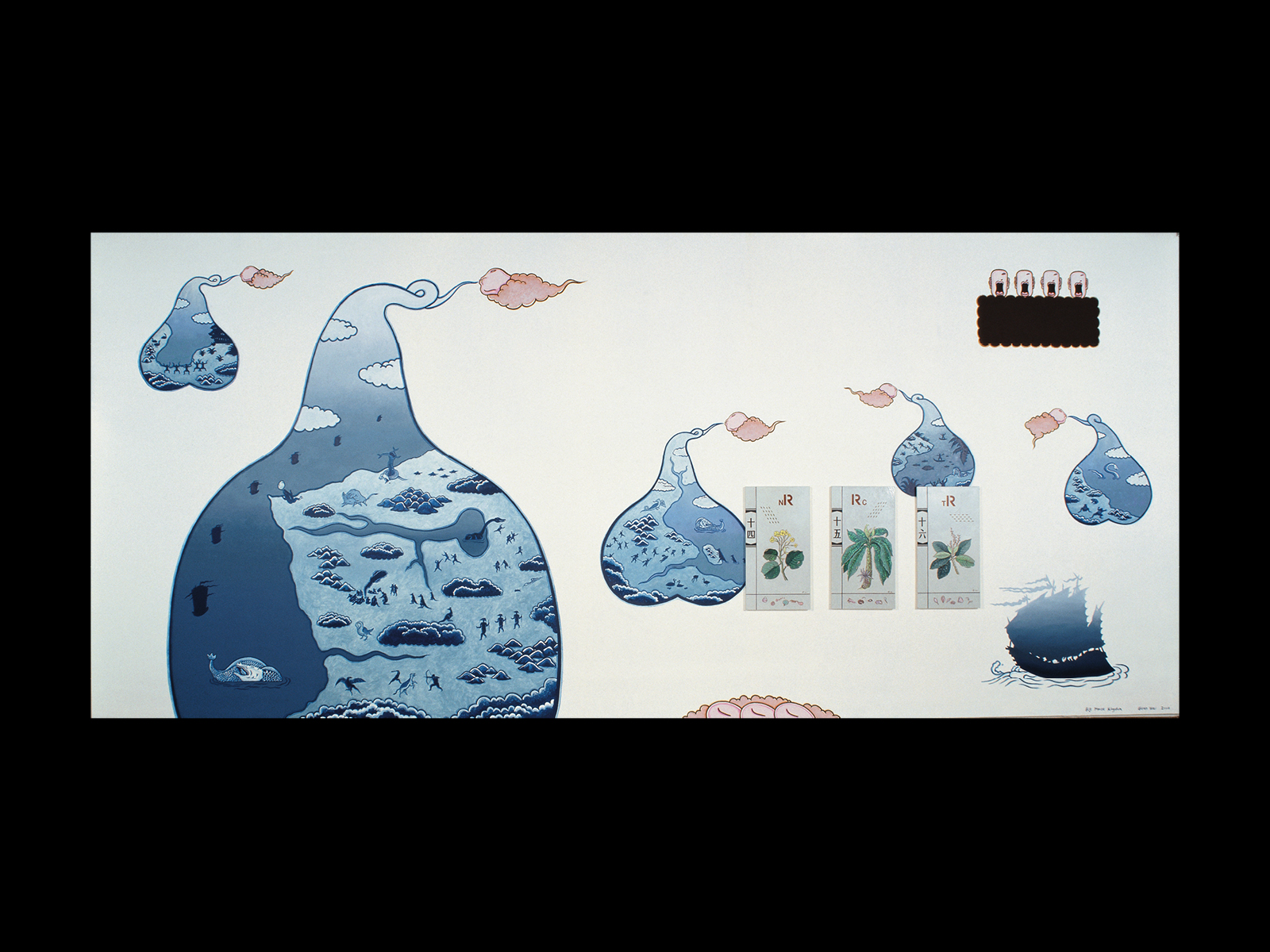

The effects of this shock were central to Guan Wei’s participation in two exhibitions in 2004 and 2008 that reinforced his interest in memories of colonial invasion. For Terra Alterius: Land of Another (2004), canvases from Exotic Flowers and Rare Grasses were shown alongside Big Mouse Kingdom (2004; fig. 10), a mural imagining an alternate history in which Chinese navigators “discovered” Australia.53 Blue-tinted vignettes, exhaled by ethereal wind spirits, were densely populated by the artist with Australian flora and fauna, dragons and chimeras, resurrected dinosaurs, animal-human hybrids, and Aboriginal silhouettes hunting, camping, dancing, or at war. This realm of peace and plenty can be starkly contrasted with the sepia-toned Echo (2005; fig. 11), shown in Lines in the Sand: Botany Bay Stories from 1770 (2008). In this “grand Chinese-style Australian history painting,” Guan Wei fused Emanuel Phillips Fox’s Landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay, 1770 (1902) and Sydney Parkinson’s (1745-71) Two of the Natives of New Holland Advancing to Combat (1770) with the distinctive painting style developed by Qing-dynasty literati Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715), envisioning a nightmarish battle among cloud-wreathed mountains.54 Despite their different visions of encounter, both works “[create] a new historical fable for Australia.”55 They also indicate a development of Guan Wei’s Australerie, from an early fascination with geographic vastness, oceanic expanse, and unfamiliar flora and fauna, to an alternate world of fantastic creatures and interweaving timelines, navigated by Aboriginal ink silhouettes.

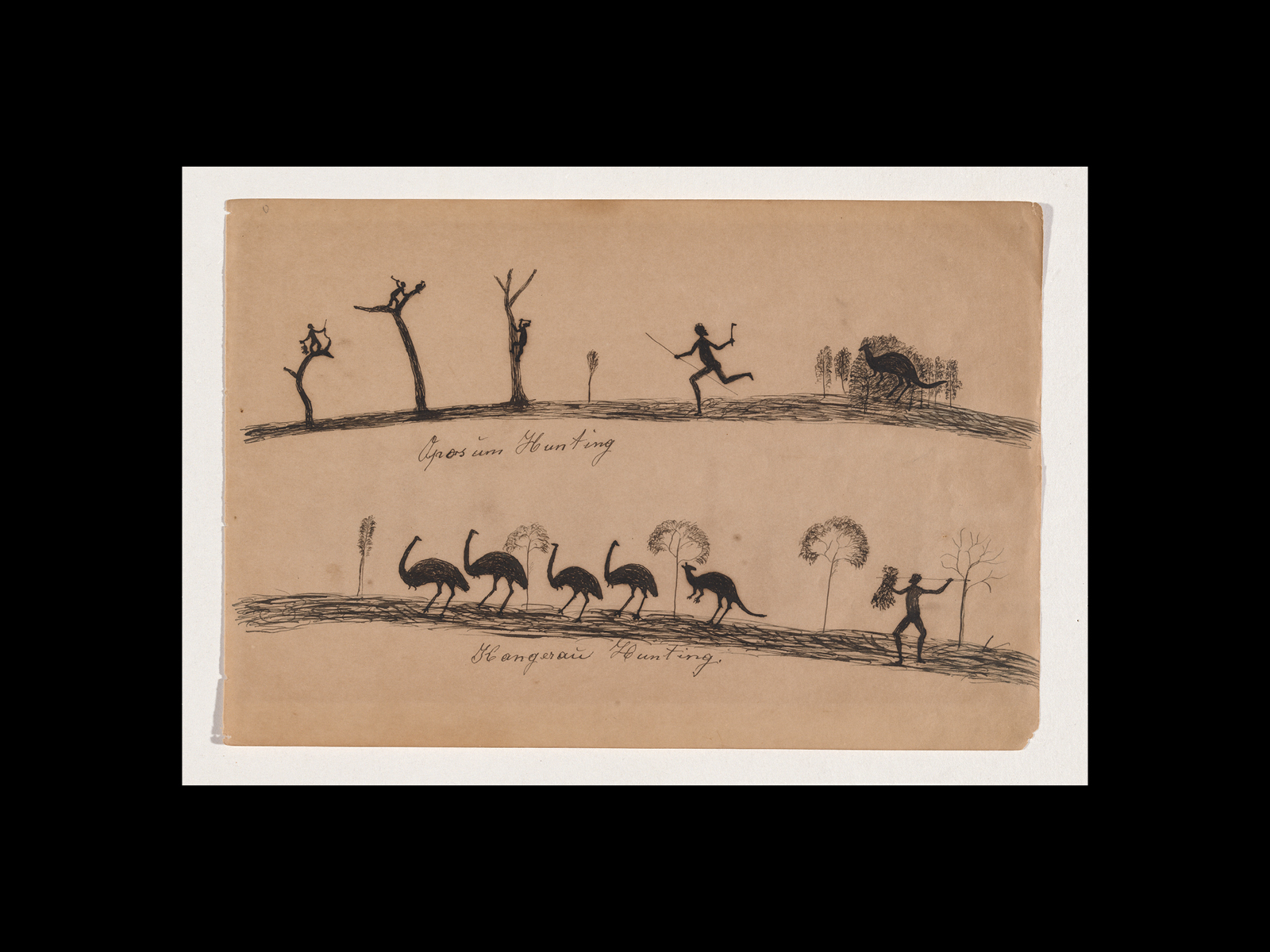

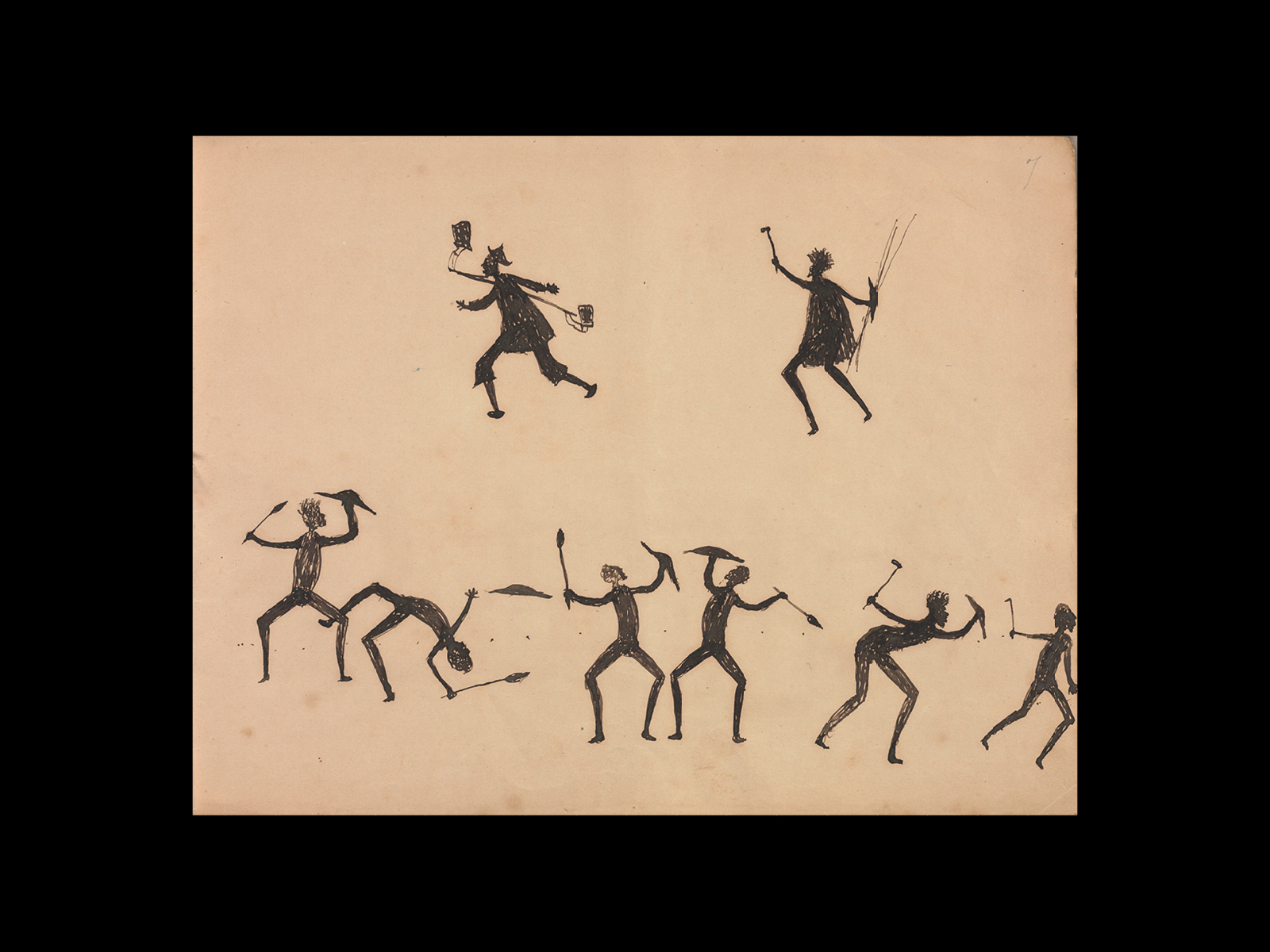

Guan Wei’s adaptation of paintings by Phillips Fox and Parkinson suggests another possible source for his Australerie in the work of a third colonial artist: Tommy McRae (c. 1836-1901), best-known for his pen-and-ink sketches of Aboriginal people hunting, fighting, and dancing. McRae’s work records the devastating impact of “successive waves of new occupants” in and around his home south of the Murray River but shows a nostalgic rather than documentary intent, affectionately tracing “traditional Aboriginal life as he had known it [and] drawing from his memories of much earlier times.”56 His White patrons also played a role in his choice of style and subject. As a “sketcher of manners” employed on commission, McRae sought to appeal to their fascination with Aboriginal culture and his sketchbooks could even be defined as an incipient Aboriginalia.57 For Guan Wei, McRae’s sketches of men hunting kangaroos and emus (fig. 12) appear to have held greatest interest, from their close imitation in Trepidation Continent and naturalistic adaptation in Target, to their fusion in Big Mouse Kingdom with his signature androgynous figures. Notably absent, however, are the “Chinesemen” who appear as supporting characters in McRae’s sketches and who would have been a significant presence in his everyday life, especially during and immediately after the goldrush of the 1850s (fig. 13). These Chinese figures appear “thrown into startled disarray by the appearance of armed Aborigines [sic],” prompting Andrew Sayers to conclude that they were likely intended to add humour, “the joke being at [their] expense.”58 Carol Cooper and James Urry, on the other hand, have explained the anachronistic combination of spear-wielding hunters with Chinese men in Qing-dynasty attire as yet another indication of McRae’s artful effort to appeal to his patrons, many of whom resented Chinese competitors.59 It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that Guan Wei found little inspiration in such stereotyping of his countrymen, choosing instead to focus on McRae’s incipient Aboriginalia.

A culminating event for Guan Wei’s Australerie was his participation in 2006 in an expedition organised by 24HR Art and Injalak Arts and Crafts. This was his first experience of the bush and left a deep impression, recorded in the series A Mysterious Land (2007). Reflecting on the expedition for Artlink, Guan Wei wrote of the “curiosity, mystery and strangeness [that] Aboriginal culture” had held for him since arriving in Australia, and the excitement with which he seized this opportunity “to go deep into Aboriginal territory” with Kunwinjku artists Gram Badari, Gershoerm Garlngarr, and Barielle Maralngurra.60 The camp inspired mixed feelings of terror and sublime insignificance:

Our camp was in a grove, my tent underneath a crooked tree ... The sound of the wind, the water and the ... strange cries coming from I-do-not-know-what-kind-of animals ... filled me with both fear and a feeling of awe ... The formidable force exuding from this wilderness ... made me think of Australia in colonial times, when forests and plains were ... harsh, savage, cruel and deserted places.61

In A Mysterious Land (fig. 14), Guan Wei translated these experiences into an intimate version of his aerial cartographies, lavishing great care on the gnarled, twisted branches and dense canopies of eucalyptus trees. Aboriginal figures run among towering anthills while terrifying animal-human hybrids linger at the edges of the composition, in the “darksome and hazy” forest kingdom of “Pan, the half-man, half-goat god ... who would frighten people with his screams.”62 As in Echo, these motifs appear within a classical Chinese landscape but remain Australian in inspiration and appearance.

Guan Wei’s Australerie ceramics

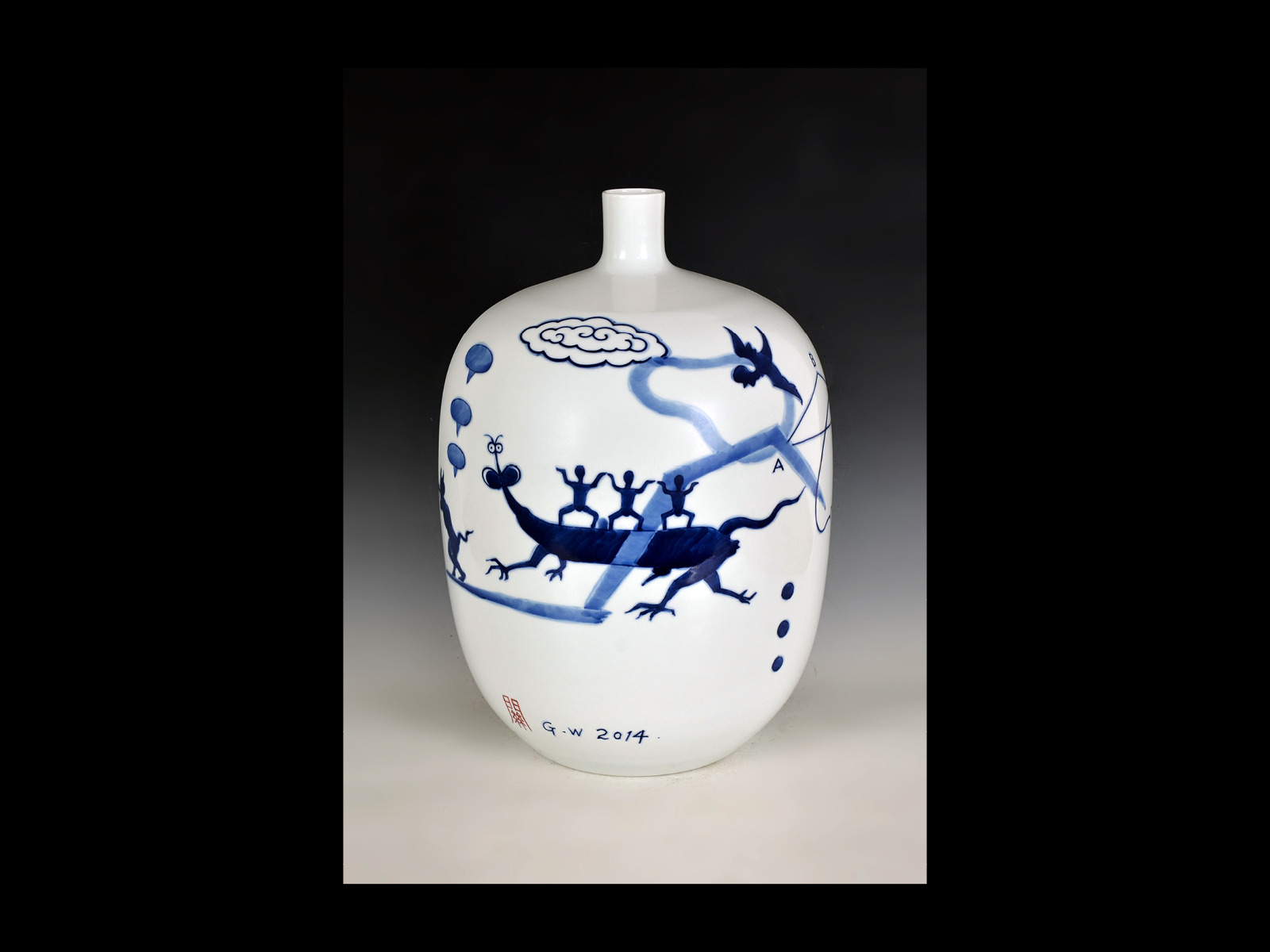

Each of these defining qualities of Guan Wei’s Australerie—his fascination with the expansive isolation of arid desert and measureless ocean, the wonder inspired by unfamiliar plants and animals, the earthy authenticity he found in Aboriginal culture, and the disruptive effects of an encounter with invading or colonising forces—can be identified in his ceramics of 2012 and 2014. On one hand, the artist’s foray into porcelain reflects the spirit of artistic enquiry that has propelled his iconography across various material supports. In our conversation in 2014, he explained his decision in these terms, citing a desire “to show people [a wider range] of things,” to challenge himself, and to guard against feelings of becoming “boring,” while also noting the increased opportunity to experiment in Beijing where studios, supplies, and assistants are relatively inexpensive.63 Conversely, this is the first time Guan Wei has worked in a medium so closely tied to Chineseness—an association he has encouraged by limiting his engagement with ceramics to the style of underglaze painting in cobalt-blue known as blue-and-white. Despite this limitation, however, each of his ceramic series bears a dense array of motifs that reflects a sustained engagement with Aboriginal Australian culture.

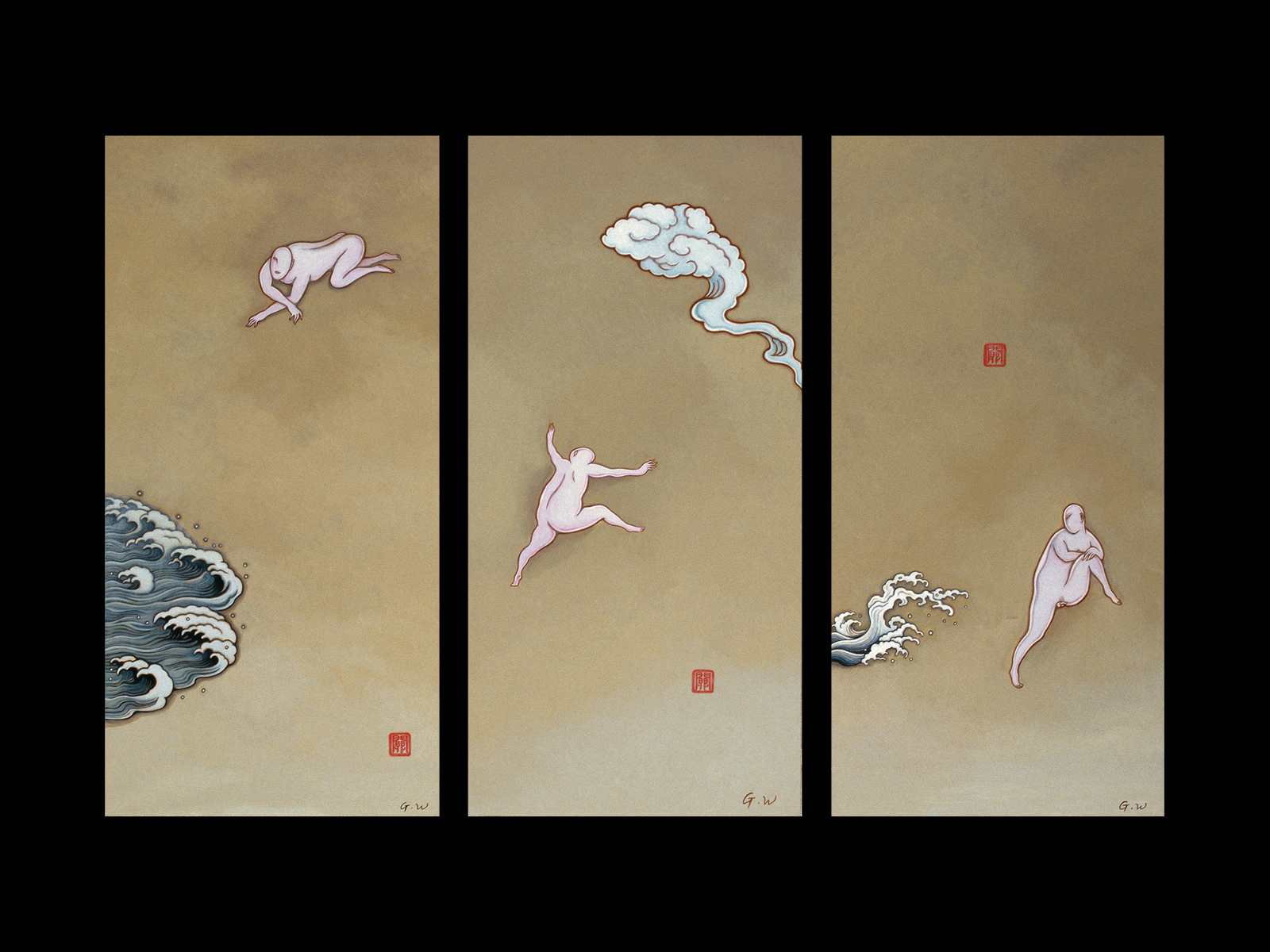

Guan Wei's first ceramics, fifteen porcelain plates and eight vases collectively titled Subdued Demons, are unapologetically eclectic and experimental. They were created during a two week stay in Jingdezhen in September 2012 with his friend, fellow artist Wang Lifeng. Guan Wei recalls this as an opportunistic foray into an unfamiliar material, inspired by its growing popularity among artists inside and outside China.64 Before leaving Beijing, he had created a series of sketches in his signature style, many derived from earlier works. The restrained pairing of nude figures with clouds and cresting waves on eight of the plates in the series (fig. 15), for example, recalls Between Clouds and Water (2001; fig. 16). Other motifs introduce themes that appear again in later, more developed pieces. These include the McRae-inspired figures first seen in his aerial cartographies; a serpentine dragon; a leaping cane toad; an eerily disembodied head in profile, one eye closed and lips pursed in concentration; distorted kangaroos, emerging from swarms of zoomorphic amoeba; floating ships; and a cast of angelic and demonic messengers, sometimes alone, sometimes in conflict. These are tentative works, with no relation between motifs or coherent narratives.

A comparable eclecticism characterises the vases in the same series, ornamented with almost identical motifs but in an arbitrary composition that contrasts with the emblematic, pictorial arrangements of the plates (fig. 17). This reveals an early challenge for Guan Wei: the difficulty of translating his sketches to a three-dimensional surface. The short duration of his first trip to Jingdezhen gave the artist little time to properly conceive designs in the round, as he did for subsequent works, forcing him instead to repeat and disperse his motifs in ornamental groups.65 A further distinction that sets the vases apart is their range of forms, again reflecting the opportunistic nature of the trip. Guan Wei has explained three forms that reappeared in later series as representative of eras to which he hoped his ceramics could be related: the first “to Aboriginal things [and] the story of Zheng He [as told in] ‘Other Histories,’” the second “to colonial times, when English people came [to Australia] and made ceramics,” and the third “to my personal patterns and styles.”66 The chronology of these associations should be noted, situating “Aboriginal things” in a distant, pre-colonial past.

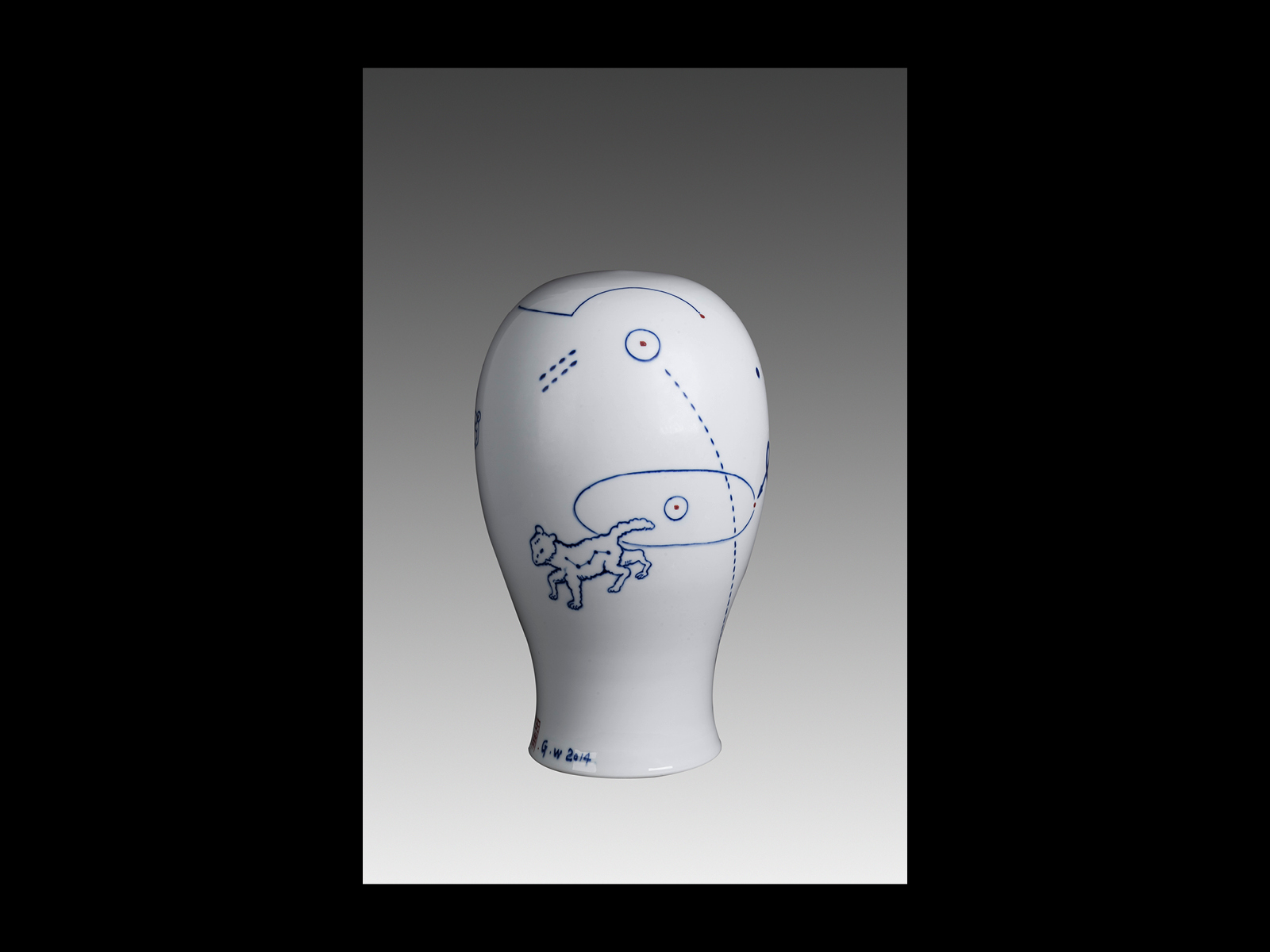

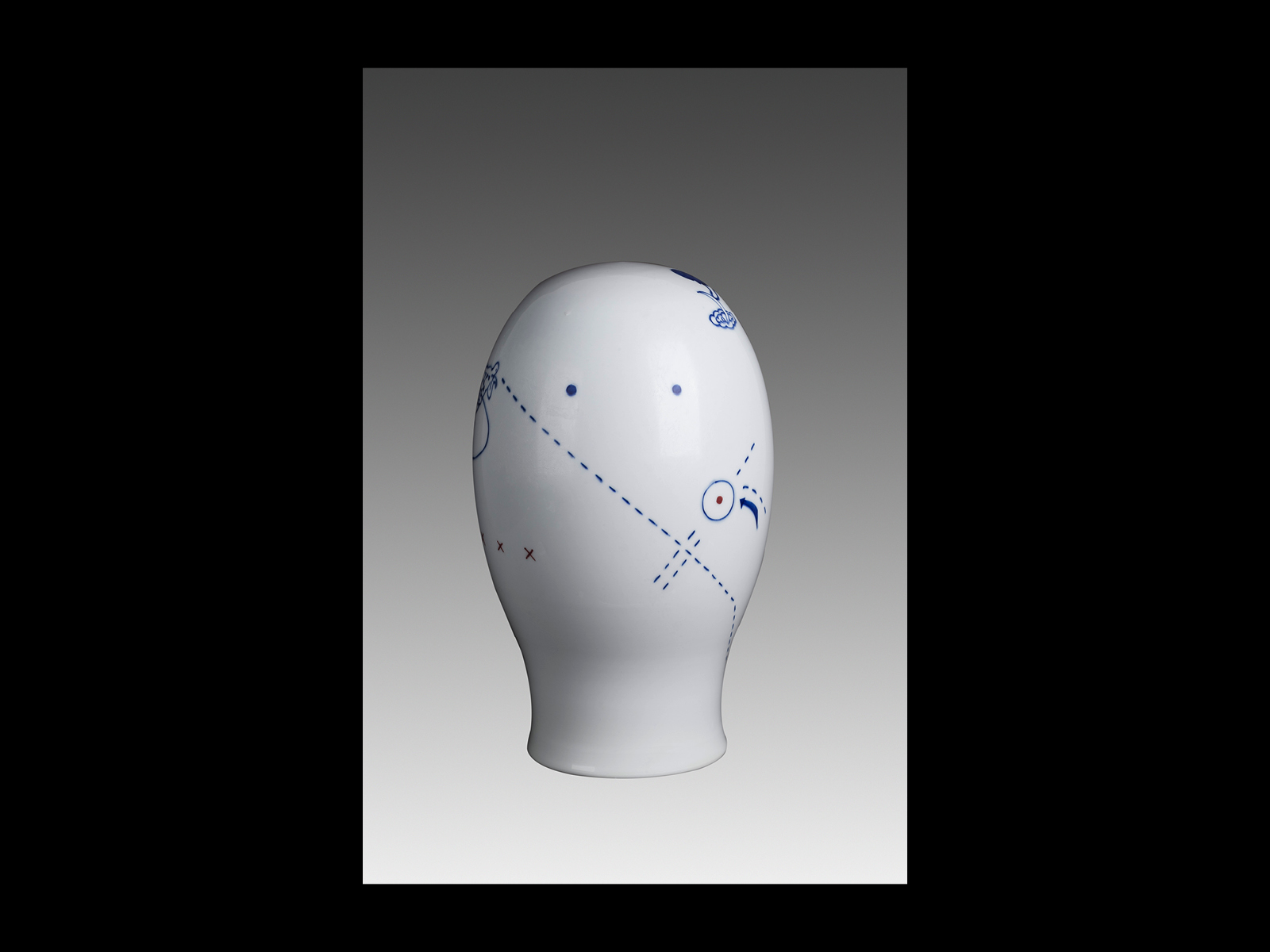

Guan Wei’s fascination with antiquity is given its clearest expression in To the Origin, the most abstract of the four porcelain series he created during two trips to Jingdezhen in 2014. These expeditions were more organised and longer in duration, allowing a considered engagement with the medium in resolved, three-dimensional compositions.67 The meandering, perforated lines, concentric circles, sweeping graphic arrows, and numerated groups of dots adorning these mouthless vessels (fig. 18) establish continuity with the cartographic and astrological symbols that first appeared in Les Vents (The Winds) (1997; fig. 19), transforming the milky-white surface of the porcelain into a map of the stars. Figures, faces, composite creatures, and esoteric diagrams become astrological constellations (fig. 20). At the same time, their anthropomorphic form suggests an inner, rather than outer void—an impression upheld by the inclusion on the seventh and eighth vessels of circles that resemble eyes and that inspire a pareidolic reappraisal of other pieces in the series (fig. 21). The lines, arrows, and dots could therefore also be a visualisation of synaptic connections between people, places, and things. Rather than constellations, the denizens of this psychological space may instead be phantoms of the imagination, fugitive dreams and desires.

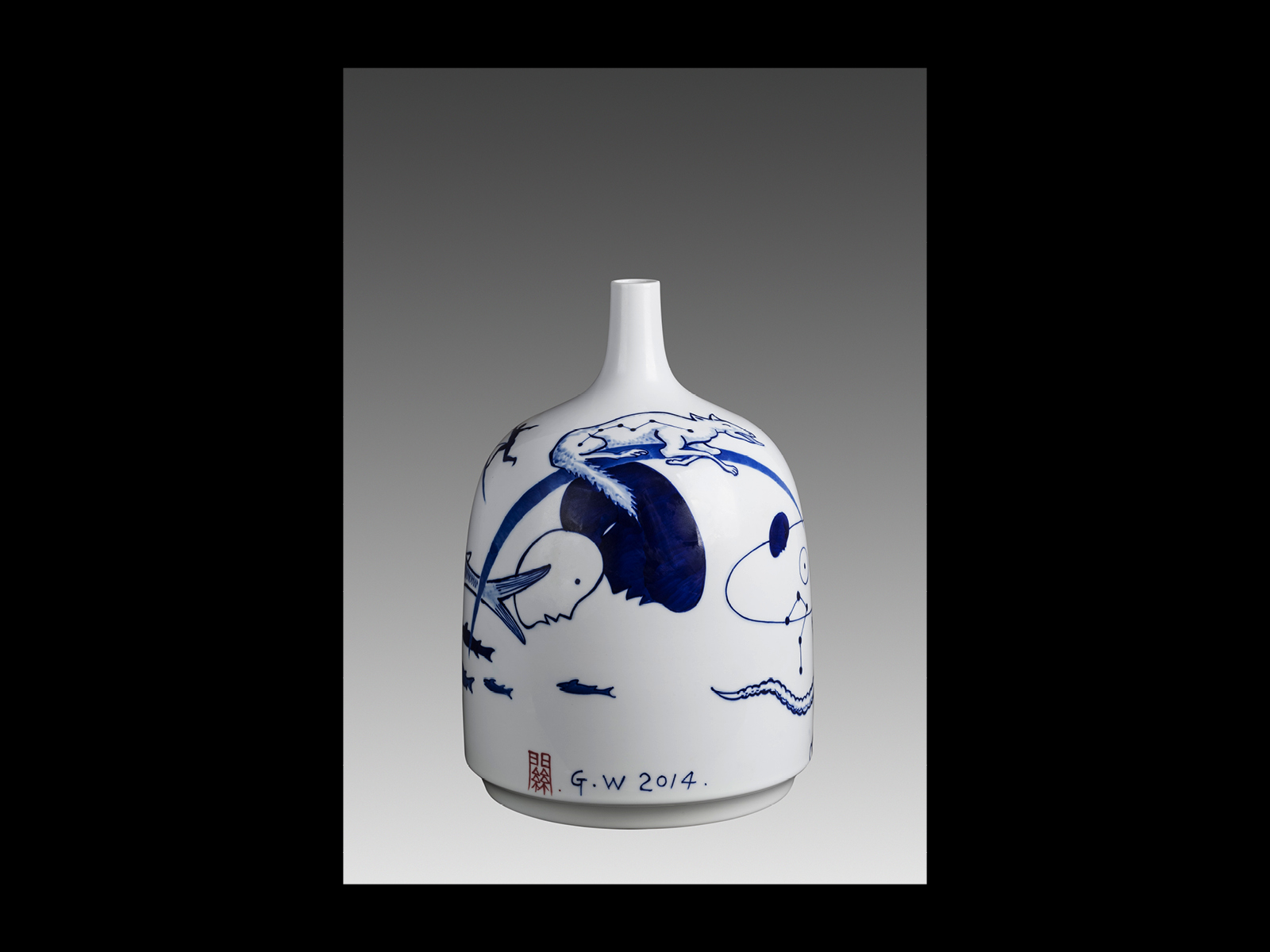

Blue Like Sky, another series of eight vessels, further develops this cartographic or astrological iconography. Yet these pieces are more densely ornamented and less formally ambiguous, with a narrow neck, sloping shoulders and defined base that suggest functional intent. Guan Wei’s repertoire of otherworldly figures and faces is further elaborated, while dots and lines recede. The astrological connotations of his menagerie are reinforced by references to Greek myth, including a rearing centaur on Blue Like Sky #6 (fig. 22) and a hieratic scorpion on Blue Like Sky #7 (fig. 23). His combination of these with the stereotypically Chinese dragon, crane and fish could be read as a juxtaposition of East and West, but this reading is complicated by the inclusion of more ambiguous, schematic designs. On the shoulder of the first vessel in the series, a diminutive figure stands on a monstrous bird reduced to the essential elements of wings, claws, and projecting head (fig. 24). On the third, the silhouettes of a warthog-like creature and a figure with arms outstretched converge between a trapezoidal diagram and a strand of DNA (fig. 25), while the final vessel teems with zoomorphic plankton, extending their legs in probing curiosity (fig. 26). Alongside myth, astrology, mathematics, and cartography, Blue Like Sky thereby alludes to the sophisticated vocabulary of lithic art, in which minimalistic forms evoke a wide range of imagined associations.

These combinations of lithic silhouettes, graphic elements, and mathematical diagrams also appear in Extraordinary World. Once again, these are functional, if narrow-necked vases, set apart only by their rounded base and a rotund profile that reinforces their anthropomorphic associations. A pair of disembodied heads in profile further supports such anthropomorphism on several vessels in both this series and Blue Like Sky, sometimes facing each other (fig. 27), at other times tenderly nestled together (fig. 28), but more frequently lone spectators to the scenes unfolding around them. Guan Wei’s representation of one face in cobalt-blue and the other in outline, one with a dotted eye and the other with a dash, implies a meeting of two worlds occasionally united in mutual curiosity, but free to navigate independent trajectories across his psychological/cosmological dreamscapes. The same figures appear in a militaristic guise in Trepidation Continent (fig. 28). Their voyeuristic presence points to the viewer’s role in decoding these mind-maps, directing our gaze to a fragment that might offer a key to the meaning of the series.

The narrative aspect of Guan Wei’s complex iconography, difficult to identify in Blue Like Sky and absent in To the Origin, comes to the fore in Extraordinary World. These vessels seem to recount a mythic journey undertaken by a race of insect-like humans, frustrated by demonic creatures and monstrous amoeba but watched over by a heavenly host of trumpeting angels. On the fourth vessel in the series, an adult, child, and dog appear stranded while overhead a boat crests a sinuous wave (fig. 29). On the seventh, a group of figures row a ship toward the setting sun across tranquil seas, while beneath them a gigantic amoeba surges to the surface with its leech-like offspring (fig. 30). On the eighth, three hieratic figures stand on a grotesque chimera, its clawed feet propelling them across a landscape of pale blue graphic sweeps, one of which cleaves the creature in two (fig. 31). In each scene, neither destination nor origin are clearly located. It is their movement that becomes important: the mythic symbolism of the journey as a metaphor for passage not only across space, but time and states of being. Even the medium of their voyage is ambiguous, variously aquatic, aerial, and terrestrial. As in all mythic forms, meaning becomes modular and open-ended, inviting the viewer to reinterpret and rearrange the narrative.

Guan Wei’s interest in lithic art reappears in Land of the Dreaming, the title of which points explicitly to Aboriginal Australia. The narrative thrust of Extraordinary World is abandoned for a frieze-like composition around the top of each vessel (fig. 32). Relationships between motifs, many of which overlap or interact, stand out—silhouettes of dancing figures, lithic crocodiles, kangaroos, emus, and fish, and swarms of zoomorphic amoeba unite in scenes of ceremony, hunting, and ritual. In the artist’s formal hierarchy, these vases correspond with the first era of “Aboriginal things”. Guan Wei’s use of the term “Dreaming” implies that he intended his figures to be read as manifestations of natural, cosmic, and ancestral forces immanent in the Australian landscape, associated with the creation of certain landmarks and essential for the navigation of regional, seasonal, and social networks of meaning. As such, a correlation can be noted with the variously cartographic, astrological, or psychological expanses mapped in To the Origin, celebrating the impenetrable mystery of the unknown and unknowable while inviting viewers to chart their own paths through the artist’s personal mythology.

Wonderland, Guan Wei’s final porcelain series, is also the most coherent in composition and content, further refining his preoccupation with an exclusively Aboriginal Australian-inspired repertoire. The composition of Wonderland #8 (fig. 33), for example, reproduces his aerial cartographies in miniature, while other vessels are painted with vignettes of Aboriginal figures running, standing, or hunting in the landscape, surrounded by eucalyptus trees and native fauna. The ambiguity of his understanding of the “Dreaming” as a primordial space of creation is absent, superseded by a terrestrial vision of Australia interspersed with silhouette portraits of Aboriginal men. Guan Wei imbues these scenes with a lingering menace and melancholy, the seemingly incongruous addition of European ships and the silhouette of a man in military uniform indicating that the series belongs to his second categorical era of “colonial times.” Yet this meeting of worlds is not framed as a colonial imposition: their encounter is one of mutual curiosity, not dispossession. These vessels therefore represent the moment when the visitor must choose between peaceful coexistence or a show of force that compels the other to submit to their will.

Displacing the White Nation fantasy

The most significant and potentially disruptive aspect of Guan Wei’s Australerie is his creation of a perspective beyond the binary logic of canonical narratives of colonisation. European and Aboriginal Australian figures alike become players in a drama not of their making: a vision of Australia as a land of exotic fascination, orchestrated by an artist whose Chinese heritage and migrant past usually cast him as the object rather than the subject of such exoticism. A similar “[dislocation of] the Anglo-Celtic from the centrefold of Australian historiography” is enacted by the landmark anthology Lost in the Whitewash: Aboriginal-Asian Encounters in Australia, 1901-2001 (2003), in the introduction to which Penny Edwards and Shen Yuanfang expose “a bipolar discourse in which discussions of the ‘Chinese Question’ and the ‘Aboriginal Problem’ [are] conducted almost entirely without reference to one another.” They invite challenges to this discourse, encouraging “conceptual overhaul of the spaces within and between which Australia can be imagined.”68 Significantly, Edwards and Shen identify writers and artists as the most likely innovators in this reorientation of the Australian imaginary, and Guan Wei could be cited as a leading architect of their desired “conceptual overhaul.” In his porcelain visions of boundless cosmic realms, chance encounters between mythic figures, and journeys of metamorphosis, Guan Wei offers a glimpse into a world beyond the censure or control of White Australian viewers.

Dean Chan once posed a provocative question: “Must every narrative on Australian hybridity begin with Bakhtin or Bhabha?”69 Although I, too, am guilty of citing Bhabha, my turn to Porter’s Chinoiserie as an alternative interpretive framework is a tentative response to this challenge. I propose that Guan Wei’s ceramics can be read as manifestations of a comparable “Australerie” with which he takes the role ordinarily monopolised by the White Australian connoisseur and excludes the latter from the conversation. Like the carved ivory figure of the God of Longevity at the heart of “Other Histories,” his Australerie ceramics could be read as artefacts of a pseudo-historical meeting between Ming-dynasty navigators and Australia’s Aboriginal inhabitants. Yet they are best conceived, like this paper, as a speculative proposal: for a new perspective on his oeuvre, a new awareness of his imaginative vision of Australia, and a new understanding of cross-cultural dialogue outside the binary bind of identity politics.

-

These are all commercial galleries, indicating the eminent marketability of Guan Wei’s ceramics as admittedly kitsch but eye-catching ornamental objects. John Clark has identified the artist’s desire to appeal to collectors as a significant factor in the development of his personal aesthetic in the 1990s, from one of improvised ephemerality to “[a] more professional [practice, for which] he has sought to guarantee the quality of his materials ... smoother and less subject to tonal or surface modulation ... at the centre of circles of appreciation and patronage which do not challenge the prolixity of his interpretation.” John Clark, “Playing with the Stars: Guan Wei’s Styles,” in Guan Wei: Looking for Home, ed. Binghui Huangfu (Singapore: LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, 2000), 9–10. ↩

-

Louisa Teo, “Chinese Art Sydney Style,” Artlink 23, no. 4 (2003): 32. ↩

-

The term “White Australian” is used here rather than “Anglo-Australian” in deference to Ghassan Hage’s critique of the latter as inaccurate and mystifying: “‘Anglo’ and ‘Anglo-Celtic’ are far from being a dominant mode of self-categorisation by White people whether at a conscious or unconscious level ... ‘White’ is a far more dominant mode of self-perception, although largely an unconscious one ... Categories such as ‘White Anglo-Saxon Protestants’ ... Anglos’, ‘Anglo-Celtic’, ‘European’, while usually communicating the specific feature of the dominant that their user wishes to emphasise, also manage to mystify ... the specific usage of each ... depending on various historical conjunctures as well as the internal struggle within the field of national power [that] I propose to call the field of Whiteness.” Ghassan Hage, White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society (Annandale: Pluto, 1998), 19, 56-57. ↩

-

Geremie R. Barmé, “Travels in Guan Wei’s Curiosity Cabinet,” in Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World–Documentation of an Exhibition, ed. Claire Roberts (Sydney: Wild Peony, 2008), 120-21. ↩

-

Natalie King, “Chinese Whispers: The Work of Guan Wei,” in Guan Wei, ed. Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru (Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006), 60. ↩

-

Victor Segalen, Essays on Exoticism: An Aesthetics of Diversity, ed. and trans. by Yaël Rachel Schlick (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 19. ↩

-

Guan Wei, interview with the author, October 15, 2014. ↩

-

Guan Wei, 2014. ↩

-

Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay (London: John Murray, 1961). For the development of this field of study, see: Oliver R. Impey, Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration (London: Oxford University Press, 1977); Madeleine Jarry, Chinoiserie: Chinese Influence on European Decorative Art–17th and 18th Centuries, trans. Gail Mangold-Vine (New York: Vendome, 1981); and Dawn Jacobson, Chinoiserie (London: Phaidon, 1993). ↩

-

David Porter, “Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 35, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 398, 400–04. ↩

-

Porter, “Monstrous Beauty,” 408. ↩

-

David Porter, “Chinoiserie and the Aesthetics of Illegitimacy,” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 28 (1999): 29–32. ↩

-

Porter, “Monstrous Beauty,” 399–400. ↩

-

Porter, 399–400. ↩

-

Adrian Franklin, “Aboriginalia: Souvenir Wares and the ‘Aboriginalisation’ of Australian Identity,” Tourist Studies 10, no. 3 (2010): 197. ↩

-

Franklin, “Aboriginalia,” 197. ↩

-

Richard White, Inventing Australia: Images and Identity 1688-1980, (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1981), 14-15. ↩

-

Franklin, “Aboriginalia,” 201–02. ↩

-

The term “settler primitivism” was coined by Nicholas Thomas in his landmark study Possessions: Indigenous Art/Colonial Culture (London: Thames & Hudson, 1999). Laura Fisher has identified a common impulse uniting this stylistic tendency with the development of Aboriginalia in the primitivist championing of motifs and forms associated with an essential Australian antiquity, fusing the penchant for African and Pacific artefacts among artists in Europe with colonial nation-building aspirations. Laura Fisher, “‘Aboriginal Mass Culture’: A Critical History,” Visual Studies 29, no. 3 (2014): 235. ↩

-

Fisher, “‘Aboriginal Mass Culture,’” 237. Fisher distinguishes four “strands of Aboriginal public culture” with this resurgence: the marketing of inland Australia to tourists “as a welcoming space of earthy and creative vitality”; the appropriation of Aboriginal culture as a central aspect of Australia’s global brand at events like the 2000 Sydney Olympics; the corporate use of Aboriginal motifs, exemplified by Qantas; and the embrace of public art projects by those who believe such commissions can aid the struggle for empowerment and visibility. Fisher, “‘Aboriginal Mass Culture,’” 238–40. ↩

-

Tony Albert, “Shifting Meaning and Memory: Tony Albert in conversation,” interview by Ivan Muñiz Reed, Art Monthly Australia 278 (April 2015): 57. See also: Tony Albert, “Shooting from the Hip: An interview with Tony Albert,” interview by Odette Kelada, Art Monthly Australia 218 (April 2009): 15; Tony Albert, cited in Andrew Stephens, “Visibility Clear,” Art Monthly Australasia 310 (September 2018): 8. ↩

-

Philippa Kelly, “Thinking about Guan Wei,” Artlink 23, no. 4 (2003): 49. ↩

-

Hage, White Nation, 16-18. ↩

-

Hage, 93. ↩

-

Ghassan Hage, “Multiculturalism and White Paranoia in Australia,” Journal of International Migration and Integration 3, no. 3–4 (September 2002): 419–22. ↩

-

Hage, White Nation, 105–06. The White Australia policy grew directly from the anxieties of Federation, which prompted many White Australians to worry “that by weakening the country’s links with Britain their fears of being swamped by Asians would become a reality.” Hage, “Multiculturalism and White Paranoia,” 422. ↩

-

James Jupp, Arrivals and Departures (Melbourne: Cheshire-Lansdowne, 1966). Assimilation found popularity after the Second World War, when declarations of support for migrants from European nations prompted “[an] expectation that Europeans who ‘looked like’ Australians would rapidly become ‘Australians’, grateful for [their] freedom and ... willing to forget [their] languages, behaviour and ‘ancient quarrels.’” A recognition from the late 1960s that the drive to assimilate was ineffective led to a policy shift toward integration, “a transitional phase in which the continuing reality of organised diversity was accepted [but] Australian loyalties ... remained central.” James Jupp, ‘Politics, Public Policy and Multiculturalism,’ in Multiculturalism and Integration: A Harmonious Relationship, ed. Michael Clyne and James Jupp (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 2011), 44–47. ↩

-

Hage, White Nation, 83. For an outline of this foundational stage in the development of multicultural policy, see Al Grassby, The Tyranny of Prejudice (Melbourne: Ae Press, 1984). ↩

-

Jupp, “Politics, Public Policy and Multiculturalism,” 42, 48. Australia Review of Post-arrival Programs and Services for Migrants, Migrant Services and Programs: Report of the Review of Post-Arrival Programs and Services for Migrants, May 1978 (Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1978). ↩

-

Tim Kendall, “Looking for New Opportunities: Sang Ye and the Discourse of Multiculturalism,” Journal of Australian Studies 26, no. 72 (2002): 76–77. ↩

-

Hage, “Multiculturalism and White Paranoia,” 429. ↩

-

Hage, 429–30. ↩

-

Melissa Chiu, “Asian-Australian Artists: Cultural Shifts in Australia,” Art & Australia 37, no. 2 (January 1999): 254–55; Melissa Chiu, Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China (Milan: Charta, 2006), 159–65. ↩

-

Wenche Ommundsen, “Tough Ghosts: Modes of Cultural Belonging in Diaspora,” Asian Studies Review 27, no. 2 (2003): 201. ↩

-

Nikki Barrowclough, “Lost in Translation,” Sydney Morning Herald (July 13, 1996), 46; John McDonald, “The Cultural Revolution,” Australian Financial Review (November 19, 2002), 18. ↩

-

Kendall, “Looking for New Opportunities,” 69. ↩

-

Marita Bullock, “‘China China’: Autoethnography as Literal Translation in Ah Xian’s Porcelain Forms,” in Memory Fragments: Visualising Difference in Australian History (Bristol: Intellect, 2012), 101–02. ↩

-

In 1992, Nicholas Jose remarked that Guan Wei had been “tested by survival [since his arrival in Australia] ... working at whatever job is available ... [a situation] compounded by language barriers, the perceived Australian ignorance or indifference towards Eastern artistic modes, and, very often, a limbo existence waiting for the Department of Immigration to make up its mind.” Nicholas Jose, “Brokering a Space: New Chinese Art, 1989–92,” Art Monthly Australia 53 (September 1992): 9–10. Over a decade later, Natalie King reiterated this narrative in her contribution to a monograph on Guan Wei’s work, noting the fortitude he had shown in navigating “the rigours of political oppression and immigration [to establish] an artistic career in his adopted homeland.” King, “Chinese Whispers,” 53. ↩

-

Bullock, “‘China China,’” 118–19. John Clark has isolated this desire as an intractable and persistent issue for all diasporic Chinese artists, “even the most radically modernist [of whom are constrained to construct ... the interpretation of their work via a notion of ‘Chineseness.’” He emphasises the power relations implicit in such stereotyping, noting that “[the] ability to mark [a work] as ‘Chinese’ ... makes a claim about the sovereignty ... of codes and their interpreters ... to actively empower [or] passively relativise” as they see fit. John Clark, “Dilemmas of [dis-]Attachment in the Chinese Diaspora,” in Modernities of Chinese Art (Leiden: Brill, 2010; originally published in 1998), 212. ↩

-

Edmund Capon, foreword to Guan Wei, eds. Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru, (Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006), 6. The biographic tendency is especially prevalent among Sinologists. See, for example: John Clark, “Playing with the Stars,” 115; Claire Roberts, “Introduction–Guan Wei: Fables for a Contemporary World, in Guan Wei, ed. Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru, (Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006), 8; Geremie R. Barmé, “Telling Selves & Talking Others,” ArtAsiaPacific 52 (March 2007): 73; and Barmé, “Travels in Guan Wei’s Curiosity Cabinet,” 124. ↩

-

Kelly, “Thinking About Guan Wei,” 49. See also: Jose, “Brokering a Space,” 9; Claire Roberts, “What Goes Around Comes Around: The Art of Guan Wei,” ArtAsiaPacific 21 (1999): 60; Lynne Seear, “Guan Wei: The View from the Master’s Chair–Guan Wei’s Feng Shui,” in Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, ed. Jennifer Webb (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1999), 180; Charles Green, “Guan Wei / Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney,” Art/Text 67 (January 2000): 94; and Dinah Dysart, “Guan Wei: Cultural Navigator,” in Guan Wei, ed. Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru (Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006), 50. ↩

-

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 2004), 52–56. ↩

-

Dean Chan, “The Poetics of Cultural Theory: On Hybridity and the New Hierarchies,” Journal of Australian Studies 24, no. 65 (2000): 53. ↩

-

Judy Annear, “Juggler of Systems,” Asian Art News 5, no. 5 (September/October 1995): 55; Evelyn Juers, “Spirit-Man Guan Wei,” Art & Australia 33, no. 3 (Autumn 1996): 432; King, “Chinese Whispers,” 84. ↩

-

Juers, “Spirit-Man Guan Wei,” 431–32; King, “Chinese Whispers,” 78. ↩

-

Guan Wei, correspondence with Natalie King, September 2005, cited in King, “Chinese Whispers,” 64–66. ↩

-

Guan Wei, “Horizontal and Vertical,” by Ouyang Yu Meanjin 62, no. 1 (2003): 188. ↩

-

Jose, “Brokering a Space,” 9. ↩

-

Roberts, “What Goes Around Comes Around,” 62; Claire Roberts, introduction to Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World–Documentation of an Exhibition (Sydney: Wild Peony, 2008), 16. ↩

-

Roberts, “What Goes Around Comes Around,” 63. ↩

-

Guan Wei, “Horizontal and Vertical,” 188. ↩

-

See, for example: Kelly, “Thinking About Guan Wei,” 48–49; and King, “Chinese Whispers,” 80–83. ↩

-

Margaret Farmer, “Terra Alterius: Land of Another,” in Terra Alterius: Land of Another (Paddington: Ivan Dougherty Gallery, 2004), 16. ↩

-

Claire Roberts, “Guan Wei: Flight Mode,” in Handle with Care: 2008 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, ed. Felicity Fenner (Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 2008), 64; Anna Lawrenson, “Lines in the Sand: Botany Bay Stories from 1770,” Art Monthly Australia 216 (December 2008): 18. ↩

-

Guan Wei, cited in Roberts, “Introduction–Guan Wei: Fables for a Contemporary World,” 9. ↩

-

Andrew Sayers, “Tommy McRae, Aboriginal Artist,” in Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Melbourne University Press, 1994), 28. ↩

-

Ian McLean, “Mysterious Correspondences between Charles Baudelaire and Tommy McRae: Reimagining Modernism in Australia as a Contact Zone,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13, no. 1 (2013): 71; Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll, “The Presence of Absence: Tommy McRae and Judy Watson in Australia, the Imaginary Grandstand at the Royal Academy in London,” World Art 4, no. 2 (2014): 228. ↩

-

Sayers, “Tommy McRae,” 44. ↩

-

Carol Cooper and James Urry, “Art, Aborigines and Chinese: A Nineteenth-Century Drawing by the Kwatkwat Artist Tommy McRae,” Aboriginal History 5, no. 1 (1981): 86–87. ↩

-

Guan Wei, “A Mysterious Land,” Artlink 27, no. 4 (December 2007): 49; Ashley Crawford, “Guan Wei Goes Bush,” Artlink 27, no. 1 (March 2007): 67. ↩

-

Wei, “A Mysterious Land,” 49-50. ↩

-

Wei, 49. ↩

-

Wei, interview. ↩

-

Wei, interview. ↩

-

Guan Wei, interview with the author, 2014. ↩

-

Wei, 2004. ↩

-

Wei, 2004. ↩

-

Penny Edwards and Shen Yuanfang, “Something More: Towards Reconfiguring Australian History,” in Lost in the Whitewash: Aboriginal-Asian Encounters in Australia, 1901–2001 (Canberra: Humanities Research Centre, Australian National University, 2003), 2, 6. ↩

-

Chan, “The Poetics of Cultural Theory,” 56. ↩

Dr. Alex Burchmore is an Adjunct Lecturer with the Australian National University’s Centre for Art History and Art Theory. He has written for a range of international publications, including the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Kunstlicht, View: Theories and Practices of Visual Culture and Oxford Art Journal. He received the award for Best Scholarly Article in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art in 2018, and inaugural Oxford Art Journal Essay Prize for Early Career Researchers in 2019.

Bibliography

Bibliography

- Albert, Tony. “Shooting from the Hip: An interview with Tony Albert.” By Odette Kelada. Art Monthly Australia 218 (April 2009): 15–18.

- Albert, Tony. “Shifting Meaning and Memory: Tony Albert in conversation.” By Ivan Muñiz Reed. Art Monthly Australia 278 (April 2015): 56–61.

- Annear, Judy. “Juggler of Systems.” Asian Art News 5, no. 5 (September/October 1995): 54–55.

- Australia Review of Post-arrival Programs and Services to Migrants. Migrant Services and Programs: Report of the Review of Post-Arrival Programs and Services for Migrants, May 1978. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1978.

- Barmé, Geremie R. “Telling Selves & Talking Others.” ArtAsiaPacific 52 (March/April 2007): 72–75.

- Barmé, Geremie R. “Travels in Guan Wei’s Curiosity Cabinet.” In Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World: Documentation of an Exhibition edited by Claire Roberts, 120–27. Sydney: Wild Peony, 2008.

- Barrowclough, Nikki. “Lost in Translation.” Sydney Morning Herald, July 13, 1996, 45–53.

- Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Bullock, Marita. “”China China”: Autoethnography as Literal Translation in Ah Xian’s Porcelain Forms.” In Memory Fragments: Visualising Difference in Australian History, 97–129. Bristol: Intellect, 2012.

- Capon, Edmund. Foreword to Guan Wei, edited by Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru, 6. Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006.

- Chan, Dean. “The Poetics of Cultural Theory: On Hybridity and the New Hierarchies.” Journal of Australian Studies 24, no. 65 (January 2000): 51–57.

- Chiu, Melissa. “Asian-Australian Artists: Cultural Shifts in Australia.” Art & Australia 37, no. 2 (Summer 1999/2000): 252–260.

- Chiu, Melissa. Breakout: Chinese Art Outside China. Milan: Charta, 2006.

- Clark, John A. “Playing with the Stars: Guan Wei’s Styles.” In Guan Wei: Looking for Home, edited by Binghui Huangfu, 6–10. Singapore: LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, 2000.

- Clark, John A. “Dilemmas of [dis-]Attachment in the Chinese Diaspora.” In Modernities of Chinese Art, 211-27. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

- Cooper, Carol and James Urry. “Art, Aborigines and Chinese: A Nineteenth Century Drawing by the Kwatkwat Artist Tommy McRae.” Aboriginal History 5, no. 1 (1981): 81–88.

- Crawford, Ashley. “A New Alphabet? Guan Wei Goes Bush.” Artlink 27, no. 1 (March 2007): 67.

- Dysart, Dinah. “Guan Wei: Cultural Navigator.” In Guan Wei, edited by Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru,13–50. Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006.

- Edwards, Penny and Shen Yuanfang. “Something More: Towards Reconfiguring Australian History.” In Lost in the Whitewash: Aboriginal-Asian Encounters in Australia, 1901–2001, 1–19. Canberra: Humanities Research Centre, Australian National University, 2003.

- Farmer, Margaret. “Terra Alterius: Land of Another.” In Terra Alterius: Land of Another, 4–26. Paddington: Ivan Dougherty Gallery, 2004.

- Fisher, Laura. “”Aboriginal Mass Culture”: A Critical History.” Visual Studies 29, no. 3 (2014): 232–248.

- Franklin, Adrian. “Aboriginalia: Souvenir Wares and the “Aboriginalisation” of Australian Identity.” Tourist Studies 10, no. 3 (2010): 195–208.

- Grassby, Al. The Tyranny of Prejudice. Melbourne: AE Press, 1984.

- Green, Charles. ‘“Guan Wei / Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.” Art/Text 67 (January 2000): 94.

- Hage, Ghassan. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. Annandale: Pluto, 1998.

- Hage, Ghassan. ‘Multiculturalism and White Paranoia in Australia.’ Journal of International Migration and Integration 3, no. 3–4 (September 2002): 417–437.

- Honour, Hugh. Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay. London: John Murray, 1961.

- Impey, Oliver R. Chinoiserie: The Impact of Oriental Styles on Western Art and Decoration. London: Oxford University Press, 1977.

- Jacobson, Dawn. Chinoiserie. London: Phaidon, 1993.

- Jarry, Madeleine. Chinoiserie: Chinese Influence on European Decorative Art, 17th and 18th Centuries. Translated by Gail Mangold-Vine. New York: Vendome, 1981.

- Jose, Nicholas. “Brokering a Space: New Chinese Art, 1989-92.” Art Monthly Australia 53 (September 1992): 9–12.

- Juers, Evelyn. “Spirit-Man Guan Wei.” Art & Australia 33, no. 3 (Autumn 1996): 431–432.

- Jupp, James. Arrivals and Departures. Melbourne: Cheshire-Lansdowne, 1966.

- Jupp, James. “Politics, Public Policy and Multiculturalism.” In Multiculturalism and Integration: A Harmonious Relationship, edited by Michael Clyne and James Jupp, 41–52. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 2011.

- Kelly, Philippa. “Thinking about Guan Wei.” Artlink 23, no. 4 (2003): 48–49.

- Kendall, Tim. “Looking for New Opportunities: Sang Ye and the Discourse of Multiculturalism.” Journal of Australian Studies 26, no. 72 (2002): 69–78.

- King, Natalie. “Chinese Whispers: The Work of Guan Wei.” In Guan Wei, edited by Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru, 53–93. Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006.

- Lawrenson, Anna. “Lines in the Sand: Botany Bay Stories from 1770.” Art Monthly Australia 216 (December 2008): 15–19.

- McDonald, John. “The Cultural Revolution.” Australian Financial Review, November 29, 2002, 18–26.

- McLean, Ian. “Mysterious Correspondences between Charles Baudelaire and Tommy McRae: Reimagining Modernism in Australia as a Contact Zone.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13, no. 1 (2013): 70–89.

- Ommundsen, Wenche. “Tough Ghosts: Modes of Cultural Belonging in Diaspora.” Asian Studies Review 27, no. 2 (2003): 181–204.

- Porter, David. “Chinoiserie and the Aesthetics of Illegitimacy.” Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 28 (1999): 27–54.

- Porter, David. “Monstrous Beauty: Eighteenth-Century Fashion and the Aesthetics of the Chinese Taste.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 35, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 395–411.

- Roberts, Claire. “What Goes Around Comes Around: The Art of Guan Wei.” ArtAsiaPacific 21 (1999): 58–65.

- Roberts, Claire. “Introduction–Guan Wei: Fables for a Contemporary World.” In Guan Wei, edited by Dinah Dysart, Natalie King and Hou Hanru, 7–9. Fishermans Bend: Craftsman House, 2006.

- Roberts, Claire. “Guan Wei: Flight Mode.” In Handle with Care: 2008 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, ed. Felicity Fenner, 64–65. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia, 2008.

- Roberts, Claire. Introduction to Other Histories: Guan Wei’s Fable for a Contemporary World: Documentation of an Exhibition, 14–17. Sydney: Wild Peony, 2008.

- Sayers, Andrew. “Tommy McRae, Aboriginal artist.” In Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century, 27–49. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Seear, Lynne. “Guan Wei: The View from the Master’s Chair–Guan Wei’s Feng Shui.” In Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, edited by Jennifer Webb, 180–181. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1999.

- Segalen, Victor. Essays on Exoticism: An Aesthetics of Diversity, edited and translated by Yaël Rachel Schlick. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Stephens, Andrew. “Visibility Clear.” Art Monthly Australasia 310 (September 2018): 8.

- Teo, Louisa. ‘Chinese Art Sydney Style.’ Artlink 23, no. 4 (2003): 32–35.

- Thomas, Nicholas. Possessions: Indigenous Art/Colonial Culture. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999.

- Von Zinnenburg Carroll, Khadija. “The Presence of Absence: Tommy McRae and Judy Watson in Australia, the Imaginary Grandstand at the Royal Academy in London.” World Art 4, no. 2 (2014): 209–235.

- Wei, Guan. “A Mysterious Land.” Artlink 27, no. 4 (December 2007): 49–51.

- Wei, Guan. “Horizontal and Vertical.” By Ouyang Yu. Meanjin 62, no. 1 (2003): 186–194.

- White, Richard. Inventing Australia: Images and Identity 1688-1980. Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1981.