Evanescence of an Artist's Model Jules Lefebvre’s Chloé

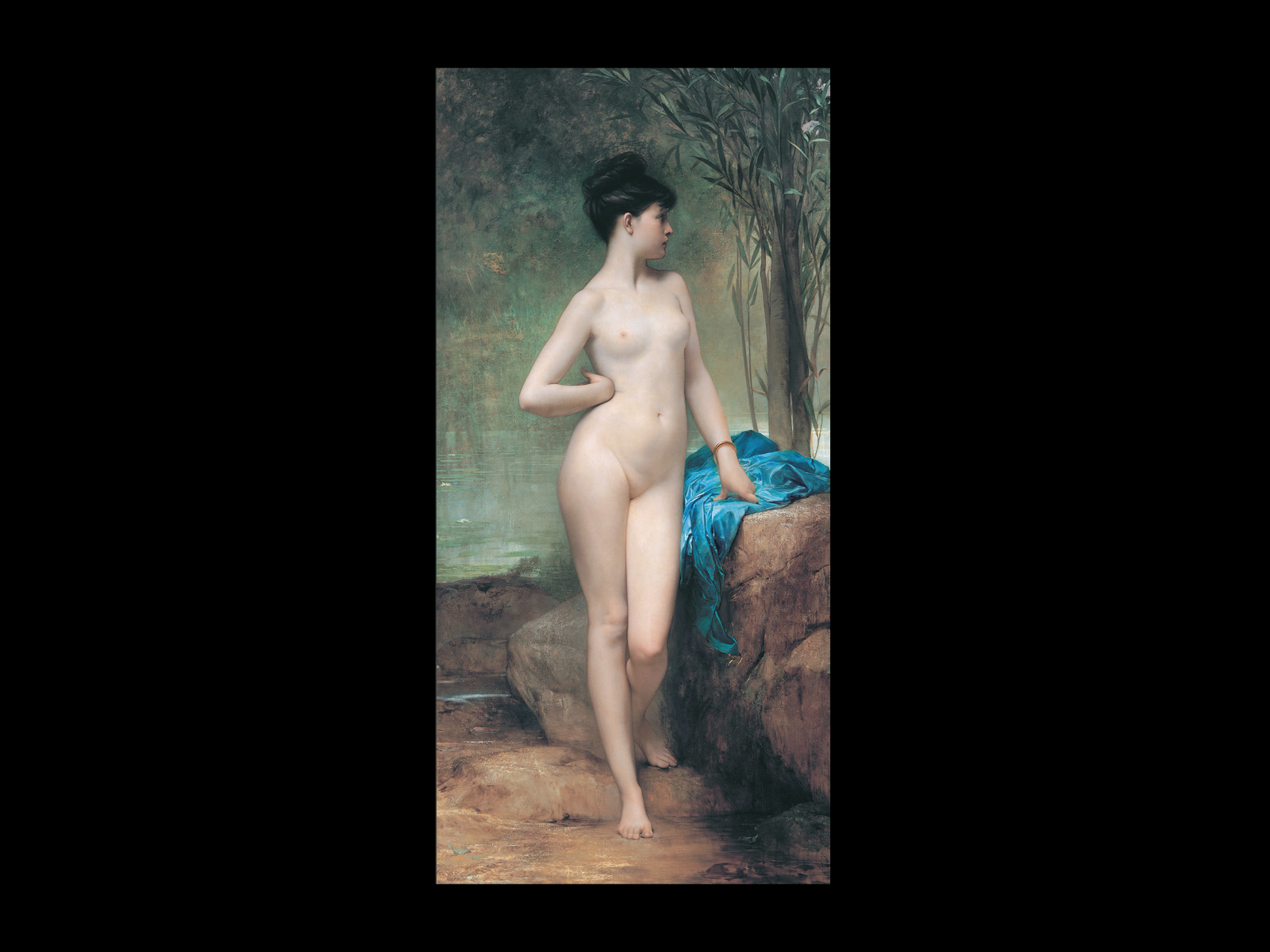

Chloé, 1875

From the time Chloé made its debut in the Australian colonies in 1879, Jules Joseph Lefebvre’s painting has been the subject of myths that tend to diminish the cultural significance of this academic artwork. Chloé is an important emblem of the cross-cultural links between the Australian and French people, and a powerful symbol of femininity in a historically male-dominated environment. The painting’s unusual positioning at Young and Jackson Hotel in Melbourne has undoubtedly contributed to its mythic status. Eminent British historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto claims myths are the basis for understanding a “people,” with the qualification that “no one can ever make sense of a people’s history without seeing it through their eyes.”1 The same can be said when interpreting myths about Chloé and the ways this painting has been received by generations of Australians. Chloé myths appear to have responded to shifts in societal attitudes. Viewers’ responses to the painting and the pleasures or anxieties these responses betray, reflect the social contexts in which the myths are constructed and negotiated. Furthermore, as Stephen Knight asserts in his study on The Politics of Myth:

The myths of a culture have two evaluative positions—they seem both distant and ethereal by not being bluntly realistic, but at the same time they are insistently present, and provide ways of thinking about the structures, values and human roles within the societies that live by and realise themselves through that culture.2

Myths reveal the behaviours and traditions of a people’s culture, filtering their proclivities through the lens of metaphor and story. Moreover, as a culture evolves throughout the ages, its myths respond to changing values and societal expectations. In her study on the myriad depictions of Joan of Arc, for example, Marina Warner argues “a story lives in relation to its tellers and receivers; it continues because people want to hear it again, and it changes according to their tastes and needs.”3 Warner claims myths about Joan of Arc have evolved because “the history of individual women and women’s roles has been so thin.”4 This “thinness” mirrors certain myths about Chloé’s model, a woman whose identity has remained a mystery. By bringing a contemporary female gaze to Jules Lefebvre’s Chloé, this paper aims to recontextualise the iconic artwork’s history, and the identity politics that may have contributed to reductive perceptions of the painting’s model.

Chloé made its debut as Exhibit 1298 at the 1875 Paris Salon, an annual French “state-sponsored exhibition of contemporary art” held at the Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées,5 where paintings, sculptures and prints were displayed in every available space and corner.6 Lefebvre, the academy painter of Chloé, was born in the French village of Tournan, Seine-et-Marne, and spent his boyhood years in Amiens,7 a northern city in the heart of the Somme which would be defended by Australian soldiers during World War One.8 Chloé was first unveiled in the Australian colonies at the Sydney International Exhibition of 1879 (September 17, 1879 – April 20, 1880),9 where it received a Special First Degree of Merit medal and high praise from the judging committee:

Lefebvre’s “Chloé” displays great skill in classic composition; it is a strong unswerving study of the female form, is well drawn, and comes boldly off the canvas. It is of a too real type to be god-like, but is honest and truthful, and treated in a chaste and perfectly natural manner.10

The following year, at an exhibition challenging its east coast rival and embracing modernism, Melbourne announced “it was ready to take its place in the world.”11 Chloé was awarded First Order of Merit at the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition and the painting received positive reviews in the press:

The “Chloé” of the Chevalier J. J. Lefebvre, a pupil of [Léon] Cogniet, was exhibited at the Salon in 1875, and is the finest study from the nude in any of the galleries. It displays that fine modelling which is the rule rather than the exception among French artists, and results from a systematic course of training in the life schools.12

A final report prepared by the commissioners of the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition was presented to the Parliament of Victoria. The report states that 1,329,297 visitors attended the event between October 1, 1880 and April 30, 1881, a number far exceeding Victoria’s population of 850,343 at the time,13 and, according to the commissioners, the exhibition had “taught the people of this and the adjacent colonies much of which they were previously ignorant.”14 However, there was another historical incident that coincided with Chloé’s debut in Melbourne: the trial and execution of notorious bushranger Edward Kelly for the murder of Mansfield policeman Thomas Lonigan at Stringybark Creek in the Wombat Ranges.15

Chloé and Ned Kelly: A Shared History of Rebellion

On the overcast spring day when the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition opened to considerable fanfare, Australia’s most mythologised figure was in no position to view the artworks on display in the fine art galleries. From August 26, 1880, until his execution three months later on November 11, Ned Kelly languished in a cell at Old Melbourne Gaol, a prison situated less than 500-metres from the Royal Exhibition Buildings in Carlton Gardens.16 Kelly remains a divisive figure in Australian history, a murderous villain who Geoffrey Robertson, the human rights barrister, has equated with a terrorist jihadist.17 However, to a substantial number of Australians, Kelly is a legendary folk hero and champion of the underdog subjected to colonial imperialism.18 Ian Jones, one of Kelly’s most respected biographers, suggests the convicted murderer and outlaw gang member was “a bushranger turned political visionary,”19 a man whose dream was an Australian republic, a nation free from British rule and the injustices suffered by the rural underclass at the hands of the squattocracy and a corrupt police force.20 Returning to Chloé, there are intriguing echoes between Kelly’s rebellion against a system of imperial injustice,21 and Lefebvre’s claim that the painting’s model had links with “a gang of low confederates.”22

During the period of Chloé’s creation, Paris was still recovering from France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the brutal oppression of the Paris Commune, the bloodiest reprisal by a European government on its own citizens in nineteenth-century history.23 Few verifiable accounts of the model for the painting remain, however, Lefebvre’s account appears to have some legitimacy. Kelly was born in 1855, and Chloé’s model, according to Lefebvre, was born in 1856-57,24 which suggests these young people were contemporaries. Kelly, the son of an Irish convict, claimed his family had been persistently persecuted by the Australian Colonial authorities,25 while Lefebvre’s model was a working-class girl from Paris who may have witnessed and escaped the brutal massacres by Versailles government troops during the oppression of the Paris Commune.26 Historian Collette Wilson reminds us that at the height of the violence:

Hundreds of women were shot or deported to the penal colonies in Cayenne and New Caledonia, many for simply being out in the street poorly dressed or for carrying a milk bottle thought to be filled with paraffin.27

A study by Penelope Ingram exposes further parallels between the embodiment of Ned Kelly and the painted incarnation of Chloé’s model, and she states “there is no doubt that Kelly is mythologised … we are, it seems, not simply fascinated by the story of Ned, but I would argue with the body of Ned”.28 In an article on how to read Ned Kelly’s armour, Ingram writes:

As a bushranger, outlaw, son of a convict, Ned is robbed of a transcendent subject position, a position that representation both requires and enacts, and is forced into the material realm of embodiment. Ironically, however, it is through this embodiment that Ned ultimately represents himself.29

Ingram explains that the interest in Kelly’s body had its origins in the practice of phrenology in the nineteenth-century, particularly its perceived potential for explaining criminal behaviour. Following his execution, Kelly’s body was dismembered and “portions of the corpse”30 were allegedly souvenired by members of the medical community.31 How does Kelly’s post-mortem dismemberment align with the history of Chloé’s model? In an 1876 interview with the American journalist Lucy Hamilton Hooper, Lefebvre claimed his model’s corpse was handed over to a Paris hospital for dissection because no one had claimed her body.32

The Artist Model who posed for Chloé

Lefebvre’s epigraph for the painting Chloé appears in the 1875 Paris Salon Catalogue: three lines from Mnasyle et Chloé, a poem by the eighteenth-century French poet André Chénier.33 Until recently very little was known about the identity of the Parisian teenager who sat for Chloé, or her career as an artist model. Already deceased, she had no control over the myths circulating about her, myths that tend to reinforce the stereotype of an artist model as described by art historian Frances Borzello:34

The fantasies about models divide into two: the model as the artist’s sexual partner and the model as the artist’s inspiration. More often than not, the sexual and inspirational roles are entwined. Fantasies focusing on the model’s sexual aspect deal with her beauty, her sexual generosity towards the artist and her scorn of conventional morality.

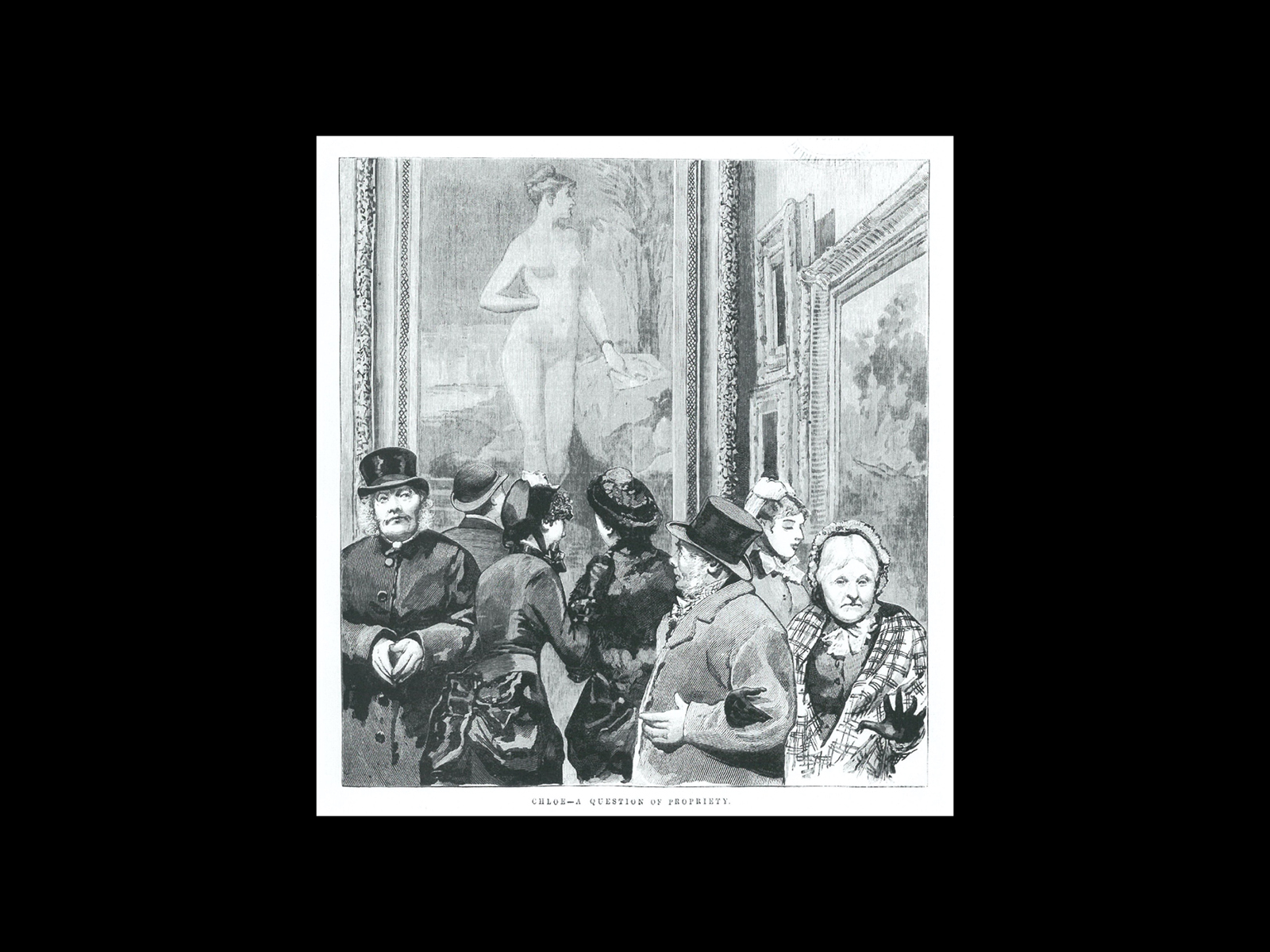

When the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) opened on a Sunday for the first time in May 1883,35 it unexpectedly “established Chloé as Melbourne’s femme fatale,” and rumours of an affair between Lefebvre and his model spread throughout the Australian colonies.36 At the conclusion of the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition, Chloé was purchased by the eminent surgeon Dr Thomas Fitzgerald (latterly Sir Thomas Fitzgerald). In 1883, Fitzgerald loaned the painting to the NGV where it was displayed “cautiously in a dim corner.”37 However, once the gallery began opening its doors to the public on Sundays, a passionate debate erupted in the press over the propriety of displaying a female nude painting on the Sabbath.

Finally exhausted by the scandal, Fitzgerald wrote to “the trustees of the gallery, requesting that ‘Chloé’ may be returned to him”.38 In her seminal essay on the NGV’s Sunday opening scandal in 1883, Stephanie Holt concluded:

‘Chloé’ was a shameless minx to some, a psychic virgin to others: a painting to be offered to an eager public to enlighten and elevate … Perhaps it is appropriate that this eruption of passions, this irresolvable conflict over such an enigmatic work … should have been so abruptly and inconclusively terminated with Fitzgerald’s reclamation of the picture. 39

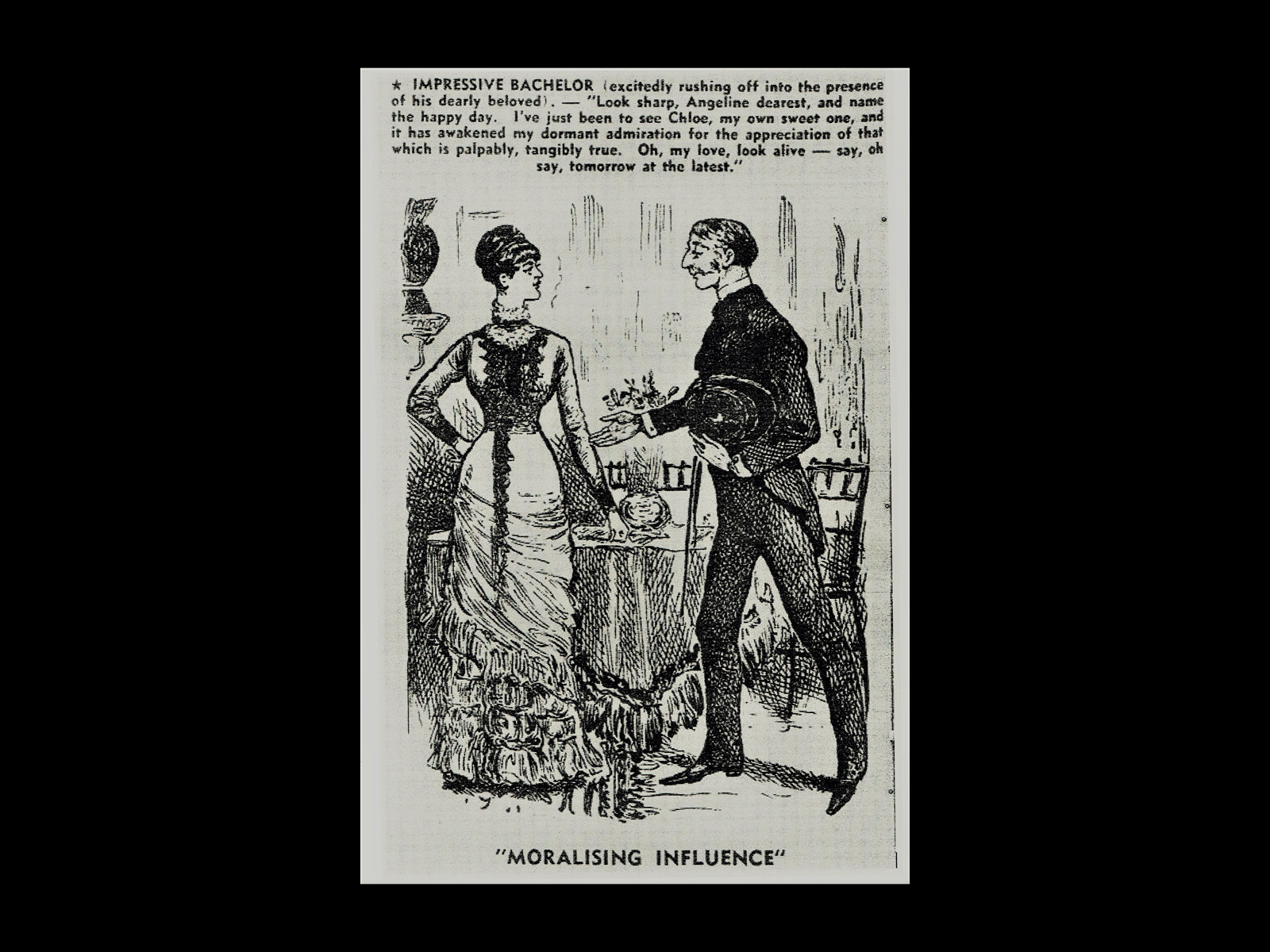

Nonetheless, four years after the painting was withdrawn from the NGV, the controversy over Chloé continued. A newspaper article claimed Lefebvre’s model was a French prostitute,40 and the Reverend B. Butchers, a “well known and outspoken Wesleyan minister,”41 declared an immoral woman had been “forced upon public attention.”42 Butchers complained that “surely it is a greater affront against public decency to have the photograph of it thrust upon the public gaze in shop windows,” and he was now concerned about the corrupting effect these decontextualised pictures would potentially have on the youth of the Colony of Victoria.43

In 1887 Fitzgerald loaned Chloé to the Adelaide Picture Gallery where the work was well received.44 However, the moral character of Chloé’s model continued to attract the scrutiny of religious viewers. Yet again, during a visit to the city of churches, the Reverend Butchers cast aspersions on Lefebvre’s model in a letter published in an Adelaide newspaper:

I refer to the exhibition of “Chloé” in your Picture Gallery, which is calculated to blunt the modesty of one sex and excite the evil passions of the other. With your permission, Sir, I would ask whether the trustees of your Gallery are aware of the fact that the “model” of this painting was a notorious French prostitute, who has since committed suicide? “Chloé” was practically expelled from the Melbourne Gallery on its intrinsic demerits before that fact was known. Will the people of Adelaide tolerate its display in view of the loathsomeness of its origin? 45

Reverend Butchers was particularly concerned that the male youth of the colonies would frame pictures of the naked prostitute and display them on their mantelpieces:

The sale of indecent pictures is prohibited in Melbourne, but as Chloé has had a recognised place on the walls of the National Gallery nobody could found a case for prosecution against anyone who might photograph her or reproduce her … This has actually been done. The lovers of the unlawfully indecent have at last got a picture to their mind … Pictures of Chloé have been bought and sold in quantities … Any fashionable larrikin with Chloé in his pocket is only “fostering a love of art” as he takes her out to look at her! No policeman can interfere with him.46

Another complaint concerning Chloé’s model appeared under the title “Lay Sermons-No. XIII. CHLOÉ. By the Brothers Nemo”:

Now, in all sobriety, the French picture of Chloé is utterly deficient in true artistic feeling … It is a pretty girl naked, neither more nor less. She hangs in the gallery there in North-terrace not to attract people to love art, or to worship the ideal, but for them to admire herself. She is showing her charms to the world, and for a pretty girl to show herself in that indecent fashion is by no means proper.47

In their condemnations, the letters’ authors had personified a painted image. Lefebvre’s model was deemed a temptress, a “pretty girl” who exposed “her charms to the world,”48 the very epitome of a “notorious French prostitute.”49 Furthermore, the Brothers Nemo believed Lefebvre’s epigraph for Chloé revealed “the true motif of the picture. Chloé is confessedly waiting for someone.”50 The brothers’ choice of language is also interesting, particularly their use of the adverb confessedly, implying that Chloé is self-aware. Writing about Chloé, Holt discussed why the nude artwork tends to be conflated with the model who sat for the painting:

This discourse reveals male anxieties aroused by a confusion between truth and representation, between the image and the reality of woman’s nature and woman’s body. This confusion echoes that posed by art in general and by the nude in particular… Is Chloé the painting; the nude painted; the name assumed by the painting’s subject; or the woman whose body is reproduced by the painter? 51

The conflation of Chloé’s model with the painting itself exposed anxieties about the public display of European art, particularly in religious sectors of Australian colonial society where the traditional role of art was, as Holt makes clear, “to exhibit moral purpose to the general viewer.”52 During the nineteenth and early-twentieth-centuries, female artists’ models were often perceived as outcasts, particularly among conservative sections of British society, working-class women presumed to be uneducated and sexually promiscuous.53 However, depictions of male artists’ models were not as sexualised as those of female artist models, particularly in the literary realm, as art historian Frances Borzello has found:

In contrast to the treatment of male models, the spectacles of stereotype through which female models have been seen have blinded authors to the facts about them and blunted their imaginations as to their use in fiction. 54

In his memoir Confessions of a Young Man, the Irish writer George Moore included an anecdote about a Parisian artist model named Marie, a young woman he claimed was “Lefebvre’s Chloé.”55 Moore arrived in Paris in 1873, only two years after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the violent suppression of the revolutionary Paris Commune by the government. Moore and the symbolist artist Louis Welden Hawkins are the only people, other than Lefebvre, recorded as having personally associated with Chloé’s model.56 Moore and Hawkins formed a close but complicated friendship while studying art at the Académie Julian in Paris. Moore’s biographer, Adrian Frazier, claims Hawkins was the lover of Chloé’s model.57 In Moore’s later life memoir Hail and Farewell! Vale, he revealed Hawkins was once employed by an ex-Communard named Vanderkirko in the same year Chloé made its debut at the annual Paris Salon.58 Vanderkirko owned a “small china factory” and he “had only just escaped with his life” during the Commune’s bloody suppression.59 When Hawkins fell on hard times, Vanderkirko offered the young artist an apprenticeship as a china painter.60 According to Moore, Hawkins consorted with dangerous criminals, and he liked to live “amongst thieves and ponces.”61 During his 1876 interview with Lucy Hamilton Hooper, Lefebvre had claimed the model who sat for Chloé was involved with a “gang of low confederates,”62 which raises an intriguing possibility. Was the model’s lover, Louis Welden Hawkins, one of the confederate gang members Lefebvre referred to?

In her first paper on the Paris Salon of 1875, Lucy Hooper sang the praises of Lefebvre’s Chloé, describing it as “one of the loveliest nude figures in the exhibition.”63 Again, in her second critique of the Salon, she claimed it was a “relief to turn … to the exquisitely pure and charming ‘Chloé’ of Lefebvre”,64 after viewing the colossal painting En Avant by Betsellère (1875) illustrated in Figure 5,65 which depicts the incumbent monarchist French president Marie-Patrice MacMahon astride his horse, brandishing a sword over some brutalised warriors.66

Hooper’s admiration for Lefebvre’s oeuvre eventually led her to his studio,67 and she wrote an article about the visit in her “From Abroad” column in Appletons’ Journal:

Does any lover of art, in an ecstasy before some fine painting representing Eve, Venus, or some undraped nymph, ever question himself or herself respecting the probable fate of the model from whose living beauty the artist has won the charm of his picture? Chance has recently made me acquainted with the history of one of those radiant originals whose graces have been immortalized by art. When visiting the studio of the celebrated artist recently, I paused in admiration before the original sketch of that exquisite image of pure and girlish loveliness, the “Chloé,” that was one of the gems of the last Salon, and that in photographic reproduction has proved so immensely popular.68

Hooper’s interest in the identity of Chloé’s model, and her acknowledgement of the contribution the model had made to the appeal of Lefebvre’s painting, betrays her progressive outlook. This is significant when considering women’s lives, throughout history, have often been portrayed “through male-authored narratives.”69 Moreover, it is evident Hooper was a storyteller, her article unfolding like the script for a play as she shared Lefebvre’s revelations about the fate of his young Parisian model:

‘The model who sat to me for that picture,’ said M. Lefebvre, ‘was but seventeen years of age; and so exquisite was her form in outline and proportion, that I was scarcely obliged to alter or idealize a single line. She sat to me [sic] during the entire winter, and in the spring I quitted Paris to travel through Holland and Belgium. On my return I found that the poor young creature was dead. She was a girl of more refinement and elevation of sentiment than is usually to be found among persons of her position, and, being in the hands of a gang of low confederates, they had attempted to force her into a way of life from which her soul revolted. Thus driven to despair, the poor child poisoned herself by washing phosphorus from friction matches, and then swallowing the decoction. She was taken to the hospital, where she died in a few hours; and as her unnatural relatives refused to claim the body, it was handed over to the doctors of the establishment for dissection. Had I but been in Paris,’ added the artist, in a tone of deep feeling, ‘I could have saved her from that last indignity, at least.’70

Hooper’s article, and Lefebvre’s claims about the social status and alleged fate of Chloé’s model, offer valuable insights into the lived experience of the teenage girl who sat for the painting. The only other first-hand account of Chloé’s model, and her possible identity, is George Moore’s anecdote in his memoir Confessions, a story which provides no specifics about her age or, indeed, her social standing. Lefebvre’s claim that she was seventeen, and that she died in 1875, also differs from the mythologised Chloé history published on the Young and Jackson Hotel:

A young Parisian artist’s model named Marie was immortalised by Jules Joseph Lefebvre (leferb) as Chloé. Little is known of her, except she was approximately 19 years of age at the time of painting. Roughly two years later, Marie, after throwing a party for her friends, boiled a soup of poisonous matches – drank the concoction and died. The reason for her suicide is thought to be unrequited love.71

If Lefebvre’s assertions were accurate, his model appears to have died within months of Chloé’s debut at the 1875 Paris Salon, and his claim about her position also implies she was impoverished. As a celebrated artist, Lefebvre was accustomed to moving in privileged circles, while according to his assessment, his young model was involved in some way with criminality.72 Yet the etymology of the noun confederate is relevant when considering Lefebvre’s judgement of the people his model was allegedly in the “hands of.” It is a word which evokes images of the American Civil War, and sepia photographs of confederate soldiers defending the southern rebel states. However, according to the cultural historian Bertrand Taithe:

In the Versailles usage, the Communards were compared with confederates, the term federates being actually used by the Communards themselves to refer to their decentralist political project. 73

Taithe’s claim is significant. If there was a veracity to the story Lefebvre shared with Lucy Hamilton Hooper, it is conceivable Chloé’s model was involved with former Communards, who, from the artist’s privileged perspective, had “attempted to force her into a way of life from which her soul revolted.”74 Perhaps his model was a teenage Communard, a petroleuse living in fear of being exposed during President Marie-Patrice MacMahon’s regime of moral order?75 We can only surmise what she may have experienced as a thirteen year-old girl during the horrors of La semaine sanglante, when up to 25,000 Parisians perished at the hands of their own government. Did she witness the brutal street executions, and hear the death-cries of her fellow citizens as they were slaughtered by a hail of bullets?

In Women in the Paris Commune: Surmounting the Barricades, historian Carolyn Eichner describes the pivotal role women played during the May 1871 revolution in Paris:

On April 11 and 12, 1871, an “Appeal to the Women Citizens of Paris,” was posted on walls and published in most of the Commune’s newspapers. The announcement proclaimed: “Paris is blockaded! Paris is bombarded! … Can you hear the canons roar and the tocsin sound its sacred call? To arms! La patrie is in danger!” 76

Women were urged to defend Paris and fight “for the long-term priority of developing women’s economic and social equality and independence.”77 Why has this chapter in modern French history been so absent from Chloé mythologies? A story of war and revolution, of women’s inspiring activism, as they challenged the class and gender barriers that had limited their opportunities and controlled their bodies.

Fact or Fantasy: Lefebvre’s Seduction of Chloé’s Model

On the eve of her 100^th^ birthday, Ethel Houghton Young, daughter-in-law of Henry Figsby Young, the entrepreneurial publican who had purchased Chloé from Fitzgerald in 1908, shared a story about Chloé’s model with Australian journalist David Ross. Ethel Young was a nineteen-year-old bride when Chloé was installed at Young and Jackson Hotel at the corner of Flinders and Swanston Streets in Melbourne, and she reminisced about evenings spent with her husband after closing time and “the painting that became a friend”:

‘I used to think it was so unfair. I was so happy while Chloé was such a sad story,’ she said. ‘She fell in love with the artist, let him paint her, and then was jilted. He paid her for modelling and she used the money for a farewell party—and then committed suicide. So sad’.78

In 1989, on her 106^th^ birthday, the remarkably lucid centenarian shared a similar story with journalist John Lahey about evenings spent with Chloé:

My husband and his brother would take turns to count the money at night, and I would sit there with all the lights out except one. In the dim light, you could not see Chloé’s background, and it looked as if she was stepping down the stairs. I loved to look at her like that. She seemed alive. She was such a beautiful young woman.79

Ethel Young’s memories of Chloé were poignant and imbued with affection, and they resonated with the story published on the Young and Jackson Hotel website. Young believed the woman had ended her life because Lefebvre rejected her, however, according to George Moore, “no one knew why” she committed suicide.80 In Moore’s Confessions he claimed some had said it was love, but he made no reference to an intimate relationship between Lefebvre and his artist model.81 Another account of the model’s suicide was published in the Australasian Post, in what appears to be a derivative version of the hotel’s narrative:

Slowly, she boiled the water in which she’d placed scores of match-heads — a poisonous variety then on sale in Paris, but since banned — purchased with the few pence that remained from her dinner party, and drank.

In a little while death came.82

Remaining true to the hotel’s version of the tragedy, there is no suggestion of an affair between Lefebvre and Chloé’s model. However, it appears possible that Ethel Young’s story may have originated in bar-room gossip, based on another memory she shared with John Lahey:

One other memory she carried away from Young and Jackson’s was about the gossip. ‘They say that women talk scandal,’ she said, ‘but most of the men take the scandal home to the women and they distribute it. I would be in the sitting room at the top of the stairs, and the men would drink below. I can tell you I listened to many very interesting conversations.83

Young’s claim about the male drinkers, and their propensity for initiating scandal, may have been the source of the rumour about Lefebvre’s affair with Chloé’s model. Young’s story also brings to mind an age-old cliché—the libidinous artist seducing his naïve young model—a stereotype the exclusively male drinkers may have projected onto the artist/model relationship.84 There are other published versions of the alleged scandal, including this excerpt from an article about Chloé on the H2G2 website, an online knowledge sharing forum founded by the English author Douglas Adams:

The truth about the model, a young French girl called Marie, is the source of much debate. She was only 19 years of age when she posed for the painting, and some say she and Lefebvre had a love affair, while others say he refused to love her. Another story is that he seduced both her and her sister.85

Further expanding on the above story, yet another version claims Lefebvre rejected Chloé’s model and married the young woman’s sister:

A young Parisian model named Marie posed for the painting when she was 19. She subsequently fell in love with Jules Lefebvre and when the artist married her sister, she was devastated. She boiled up phosphorus match-heads, drank the poisonous concoction and tragically, she died in terrible agony at 21. Or so they say!86

In the above account, the “Or so they say!” disclaimer implies, at least in part, that the story was inspired by hearsay. Consequently, the original commentary provided by the Young and Jackson Hotel, a story which appears to be a conflation of colonial newspaper articles and George Moore’s Lefebvre’s Chloé anecdote, may have been expanded upon and mythologised over many decades as a consequence of bar-room gossip.

Jules Joseph Lefebvre: The Political Artist?

At the pinnacle of his artistic powers in the late nineteenth century, Lefebvre was a celebrated academic artist, a member of the French Institut and Commander of the Legion of Honour. Lefebvre’s paintings of the female nude were world-renowned, and when he painted Chloé in 1875, he was already a recipient of the coveted Prix de Rome for his mythological painting La Mort de Priam (1861), and a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour for La Vérité (1870) “avec sa nudité éclatante et son charme souverain” (with her sparkling nudity and sovereign charm).87 In 1872 his classic nude La Cigale was exhibited at the annual Paris Salon, and the painting is now a highlight of the National Gallery of Victoria’s International Collection.88 However, for a man who had on two occasions painted the portrait of the Prince Imperial89 and was a close friend of Sully Prudhomme, the winner of the 1901 Nobel Prize for Literature,90 Lefebvre had risen from humble beginnings. The younger of two sons, he had been destined to take over the family bakery in Amiens, but once his prodigious talent emerged his father encouraged him to train as an artist.91

From the day Chloé made its debut at the 1875 Paris Salon, French critics penned and published their opinions about the painting and its creator. Translations of these French texts, some written well over a century ago, provide valuable insights into Lefebvre’s character and his relationship with Chloé’s model. Mario Proth, a French journalist, writer and literary critic, wrote an interesting analysis of Lefebvre’s political persuasions in his review of the 1875 Paris Salon. Quoting from a conversation he had overheard at the Salon concerning the Ossianic theme of Lefebvre’s work Rêve (The Dream, 1875),92 Proth claimed viewers suspected the painting was the artist’s homage to the deposed Second French Empire:

Ossian, is he not one of the bards that the imperial regime honours? I suspect Mr Lefebvre… who made such a nasty noise last year, I suspect he involuntarily symbolises in this tranquil and striking allegory, the slow but genuine fading of a Bonapartist dream.93

Gaelic poems of the mythic warrior Ossian were collected and translated (and possibly forged) in the late eighteenth century by Scottish writer James Macpherson.94 In an analysis of the Romantic French writer Chateaubriand’s response to the Ossian poems, professor of French literature Colin Smethurst discovered Napoleon Bonaparte’s deep affection for the Gaelic warrior:

Around 1800 … Ossian was not just a fashionable literary mode … Napoleon himself was an Ossian fan because he was mainly drawn to Ossian’s ‘heroic, epic aspect’.95

Moreover, supporting the insinuations Proth had overheard at the Paris Salon, and the notion that Lefebvre’s Ossianic painting betrayed the artist’s hopes for a Bonapartist restoration, Scots scholar David Hesse discovered:

In 1811 Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was commissioned to paint the ‘Homer of the North’ for Napoleon’s bedroom at the Quirinal Palace in Rome, a painting now known as Dream of Ossian. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) was said to be deeply fond of the Highlander and apparently compared Ossian to ‘the whisper of the wind and the waves of the sea’.96

Lefebvre’s hankering for the deposed Bonapartist empire in the nascent days of the Third French Republic had not gone unnoticed. Proth’s review reveals an embarrassing episode at the 1874 Paris Salon when Lefebvre exhibited his portrait of the Prince Imperial, the exiled son of Napoleon III and his unpopular wife, the Empress Eugenie. Exhibiting a portrait of the young man the Bonapartists were hailing as the next Napoleon angered critics who assumed the acclaimed academician was anti-republican. At the 1875 Salon, although Proth gave Chloé a glowing review and acknowledged Lefebvre’s exceptional talent, he had to concede there was a measure of truth in the criticisms levelled at the artist:

Mr Jules Lefebvre, ex-teacher and portraitist of the one who will never be Napoleon IV, is one of the young talents whom the empire has, I hope, only momentarily spoiled!97

Jules Claretie, a contemporary of Mario Proth, also commented on Lefebvre’s portrait of the Prince Imperial in his biography of the artist. Claretie was an eminent novelist, playwright and critic, and a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour,98 and he suspected Lefebvre’s political statement may have influenced art critics’ assessments of the controversial portrait:

At the Salon of 1874, Jules Lefebvre exhibited a portrait of the Prince Imperial. Oh! the foolishness of politics! What we saw then, in this painting, was not the painting itself, rather, it was a manifestation of the party, and we judged it badly, since we did not judge the work intrinsically.

Today, I would like to see the portrait of the teenager who died as a hero in Zululand. Lefebvre has kept a study in his home—the head alone—and it is a masterpiece. The following year, Jules Lefebvre exhibited a Chloé of an exquisite model and a fantasy, the sketch for which I found the other day at François Coppée’s place: it was The Dream.99

Lefebvre’s portrait of the Prince Imperial was deemed provocative due to simmering tensions between republicans, monarchists and Bonapartists in the volatile early years of the Third French Republic. Based on Proth and Claretie’s assessments, Lefebvre had remained loyal to the Bonaparte family, and he may have harboured hopes for a restoration under the leadership of the Prince Imperial. Before the collapse of the Second French Empire, Lefebvre enjoyed the patronage of the French imperial family, including Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, Napoleon Bonaparte’s niece. Princess Mathilde was one of the favourites of Parisian salon society, and she purchased Lefebvre’s painting Les Pèlerins au couvent de San Benedetto (1865) for her private art collection.100 Moreover, Lefebvre’s 1874 portrait of the Prince Imperial was his second painting of the teenager. Art historian Alain Galoin tried to imagine the sombre mood Lefebvre may have experienced on 17 July 1870 as he painted the 14-year-old prince at the emperor’s country palace, only two days before Napoleon III declared war on Prussia:

At the time when the prince posed for Jules Lefebvre, it was during the last days of a happy and carefree childhood in the palace at Saint-Cloud, which was his last home in France, and a place he would never see again. The artist made an intimate portrait of the adolescent, with great psychological depth. The face is serious, the smile has deserted his lips, and the expression is sad and nostalgic, as if the son of Napoleon III was aware of the situation. He turns his head to the left of the picture, behind him, towards the already distant memory of the splendours of the empire.101

Lefebvre’s nostalgia for the privileged life he enjoyed during the Second French Empire and his affection for the young prince whose portraits he had painted, may have intensified following the 1874 French by-elections which gave the republicans a convincing majority, leaving only six Bonapartists and one monarchist in the National Assembly. Sudhir Hazareesingh, a scholar of modern French history and politics, claims “Post-Second Empire Bonapartism was politically authoritarian, and many of its members were directly involved in attempts to overthrow the Republic in the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s.”102 In the post-Commune years, women, more often than men, were targeted by the authorities. In 1872 at a benefit for the Association for Women’s Rights, a letter of support from Victor Hugo was “the highlight of the evening. Women, he argued, were virtual slaves. These are citizens, THERE ARE NOT CITIZENESSES. This is a violent fact; it must cease.” 103 Nonetheless, less than a year after Hugo’s appeal for the fairer treatment of women, the Association for Women’s Rights was barred from holding further meetings. By 1874, the French President Marie-Edme-Patrice-Maurice MacMahon, and his Prime Minister the duc de Broglie, were enacting a regime of moral order, particularly against women who were deemed too emancipated and suspected of being former-Communards:

Broglie’s aim was to ‘re-establish moral order’. If he could not restore the monarchy, he hoped ‘to make Marshal MacMahon a veritable regent under the name of president, and France under the Republic a monarchy minus a king’. To this end, he replaced Thiers’s prefects with Bonapartists.104

The government oppressions also had religious overtones. According to the French historian Jacques Benoist, on 24 July 1874:

The Assembly approved building the Sacré-Cœur (Sacred Heart) Basilica on the Montmartre hilltop where Generals Lecomte and Thomas had been shot: ‘there the communards had spilled the first blood, there would be built an expiatory church.’105

The implications of Lefebvre’s loyalty to the Prince Imperial, and the recently deposed Second French Empire, are significant when considering myths about Chloé and the nude teenage girl who sat for the painting. They reveal the political rivalries playing out in Paris at the time of Chloé’s creation, a situation that may have complicated Lefebvre’s relationship with his proletarian model. Her nudity, the artist claimed, represented the naiad in André Chénier’s romantic idyll Mnasyle et Chloé. However, on a more intrinsic level, the painting could also be interpreted as Lefebvre’s tribute to the poet martyr: Chenier was executed on July 25, 1794 after being convicted of “conspiracies, plots and counter-revolutionary manoeuvres,” in the final days of Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre’s horrific Reign of Terror.106 In 1875, tensions between the bourgeoisie population, those who had supported provisional leader Adolphe Thiers’s brutal oppression of the Paris Commune, and the proletariat who had pinned their hopes on the egalitarian principles of the crushed revolutionary government, still festered in the City of Light during a period of post-war rebuilding and renewal.107 Moreover, translation and close analysis of historical textual sources revealed no evidence of a love affair ever having occurred between the artist and his model, or anything to suggest he had married her sister. In 1869, five years before he painted Chloé, Lefebvre married the accomplished pianist Louise Deslignières, eldest daughter of Madame Marie Deslignières, imperious headmistress of the Pension Beaujon, an elite private girls’ school situated close to the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Lefebvre, reputedly, was a devoted and faithful husband, and the deeply religious couple had eight children.108 The artist’s conventional family life may surprise when compared with the nude subjects of his paintings. Nonetheless, it can be supported by none other than his former student George Moore. In Moore’s memoir he claims Rodolphe Julien asked him, and his fellow students, to remember Lefebvre “has a wife and eight children,” when he urged them to vote for Lefebvre to receive the medal of honour.109 François Pédron, a French journalist and historian, also offers this interesting critique of the artist’s reputed fidelity:

The austere Jules Lefebvre who only painted … femmes fatales, without being unfaithful to his own … [the] father of many children, overwhelmed by commissions, hardly had time to step out of his studio. He led the life of a (married) monk so as to ensure the most lecherous of productions.110

Art historian Gabriel Weisberg claims Lefebvre was well respected by his female students at the Académie Julian, and that both “Bouguereau and Lefebvre apparently related well with their young female students without taking advantage of their position.”111 According to Weisberg, the sensitive nature of the artists’ subjects made them “appropriate teachers” for young women during the nascent years of their artistic development.112

Chloé: Australia’s Mythic War Maiden

A submission by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) to The Historic Buildings Council claimed “Chloé has been featured in overseas newspapers and described as perhaps Australia’s most famous painting and a nude version of the Mona Lisa.”113 Moreover, the following quote from a World War I newspaper article demonstrates the importance of the Young and Jackson Hotel to an ill-fated Australian soldier:

Private A. P. Hill, a Castlemaine soldier, who was killed in action some time back, sailed from Melbourne in the troopship Demosthenes in December 1915, and when leaving the shores of Australia young Hill and a comrade named Baker put a message in a bottle, and cast it upon the ocean … in January 1918, the bottle came ashore … “Demosthenes, 31/12/15. To the finder of this bottle—take it to Young and Jackson’s, fill it, and keep it till we return from the war … (We are on our way).114

The famous hotel and its “world-known painting Chloé”,115 proved irresistible for men and boys returning from the fighting. However, in 1919 the Department of Defence ordered the hotel’s closure to prevent it serving soldiers who had returned to an Australia ill-prepared to accommodate them.116 Chloé’s significance to Australian soldiers originated during World War I, and the phenomenon continued between the world wars, when enjoying a drink with Chloé became a popular ritual for male visitors to Melbourne.117 By the commencement of the Second World War, Chloé and the Young and Jackson Hotel were so embedded in Australian military mythology, the 2/21st Australian Infantry Battalion included them in their official march song:

It’s a long way to Bonegilla

It’s a long way to go

It’s a long way to Bonegilla

To see the Murray flow

Good-bye Young and Jackson’s

Farewell Chloé too

It’s a long way to Bonegilla

But we’ll get there on STEW.118

In 1945, West Australian traveller Peter Graeme compared Chloé’s iconic status to the Sydney Harbour Bridge: “Chloé is to Melbourne what the Bridge is to Sydney. From the soldier’s point of view of course.”119 He confirmed Chloé’s significance to Australian servicemen when he wrote: “All over Australia you meet men who have seen her. She is a soldier’s pilgrimage when in Melbourne… Chloé belongs to the Australian soldier.”120 Graeme shared his initial response to the painting, and described how he recognised in Chloé “a strange mystic hold that is explained only when you find yourself applauding the artist for having painted her just when he did.”121 Towards the end of his story, he recalls the day he met a soldier at Young and Jackson Hotel. The soldier was holding three drinks and after he carried them from the crowd, he “stood in front of Chloé. One after the other he drained them.”122 When Graeme offered the soldier another drink, and enquired why he had drunk three beers in quick succession, the soldier explained he was keeping a promise:

Keepin’ a promise we made to Chloé—three of us—twelve months ago when we were goin’

North—to have a drink with her when we came back.”

He paused.

“Here’s the best,” he said, and I nodded in agreement.

“Where’s your mates?” I asked.

He was looking at Chloé as he answered, as though explaining their absence.

“I buried ‘em at Scarlet [sic] Beach.123

Graeme’s article elucidates how a pilgrimage to Young and Jackson Hotel, and having a drink with Chloé, brought comfort to Australian soldiers. The man he described had lost two of his comrades at Scarlett Beach in New Guinea and drinking a beer with Chloé in their honour appears to have been part of his grieving process. As Graeme concludes in his poignant tale, Chloé may have been “the symbol of the feminine side of his life. That part which he puts away from him, except in his inarticulate dreams.”124 Graeme’s comment reveals the way boys and men, traditionally, have been conditioned to suppress their innermost fears and emotions, especially during times of warfare.

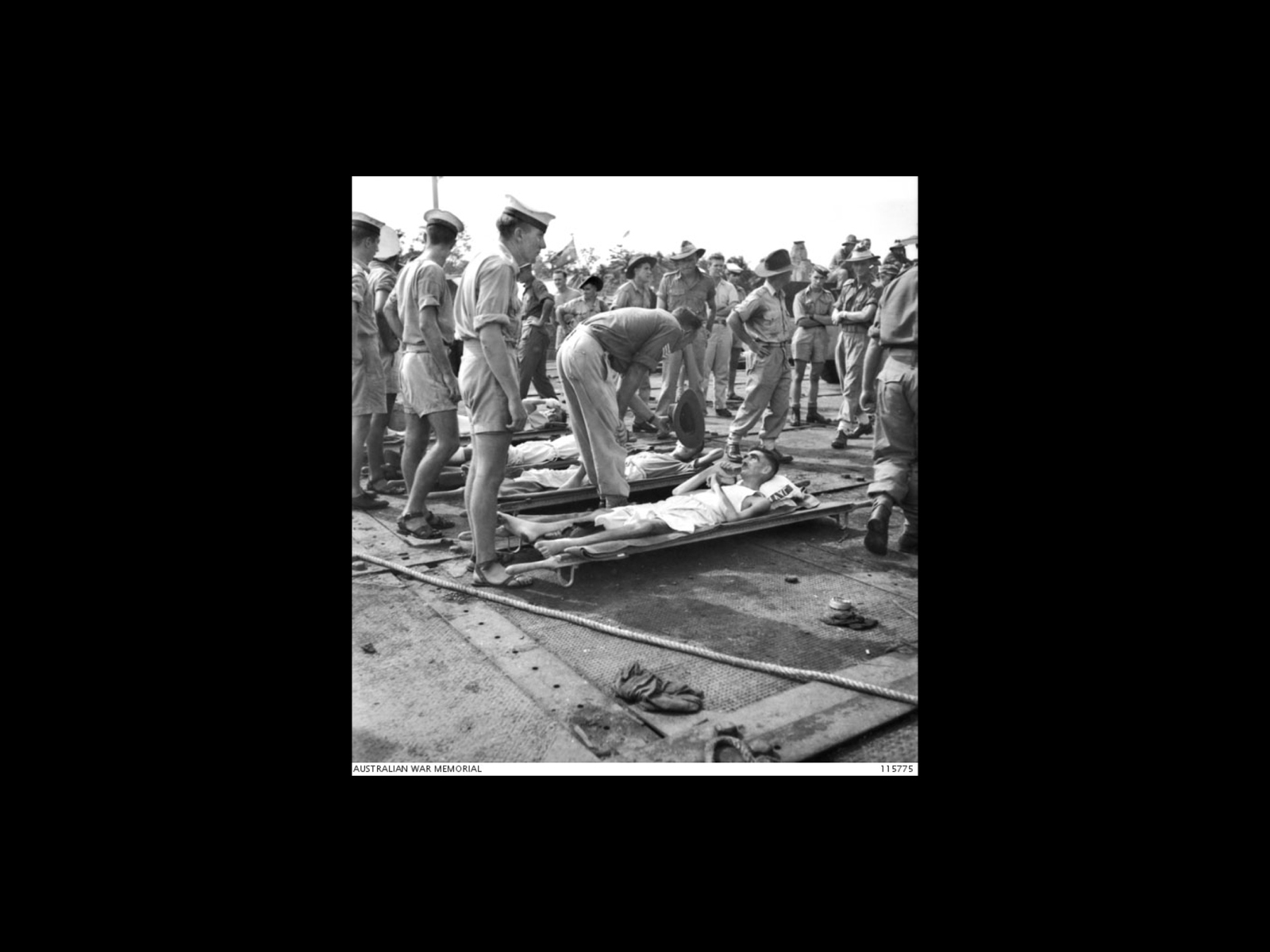

Chloé also played a crucial role in the evacuation of Australian soldiers from a Japanese prison camp on the Indonesian island of Ambon after the Second World War had ended.125 These were soldiers from the 2/21st Battalion, the men who had included Chloé in their official march song “It’s a Long Way to Bonegilla.”126 For over three years, the men “endured a living hell at the hands of their captors in conditions so appalling that many died from starvation or disease.”127 Cruel treatment from their own Australian officers only added to their suffering. Intent on curtailing bandicooting (the stealing of other men’s vegetables), senior officers constructed a barbed-wire cage with “metal tentacles … capable of drawing blood at every turn”,128 where pilferers were detained overnight with “little protection from the elements.”129 Only twenty-three percent of the Australian soldiers imprisoned on Ambon survived the war, and those who did were close to starving by the time they were evacuated.130 When news arrived of Japan’s surrender, the prisoners’ hopes for liberation quickly turned to frustration; Japanese officers in control of the camp refused to give them radio access. Three weeks later, when they were “finally granted access to their own radio transmitter,”131 their SOS message was received on the neighbouring island of Morotai. However, requiring confirmation that the message was from an Australian prison camp, the operator “posed a series of questions only a dinky-di Aussie could answer.”132 One of the first questions he asked John Van Nooten, a Melbourne soldier, was “How would you like to see Chloé again?”133 When Van Nooten replied “Lead me to her,” the operator asked “Where is she?” Van Nooten responded with Young and Jackson’s, finally convincing the operator he was “a bloody Australian.”134

In her essay “The History Question: Who Owns the Past?” Inga Clendinnen examines the role myths play in the development of national identity. Using Banjo Paterson’s poem “Waltzing Matilda” to expound her argument, Clendinnen discusses why the out-dated swagman trope at the heart of “Waltzing Matilda,” with its limiting stereotype of Australian male identity, still “sits, comfortable, unexamined, in the contemporary collective consciousness.”135 Clendinnen claims “a successful myth only grows more potent with exploitation” and a historian’s task is “to unscramble what actually happened from whatever the current myth might be.”136 This describes the approach I have adopted in this paper for deciphering Chloé mythologies. Archival research and textual analysis provided a methodological framework for interrogating the origins of Chloé, and the source of myths that have contributed to perceptions about the character of Lefebvre and his enigmatic Parisian model. Additionally, by including translated extracts of reviews by French art critics written so soon after the Franco-Prussian war and the Paris Commune of 1871, and exploring the social heritage and political ideology of the artist and his model, this analysis challenges reductive myths about the painting, and offers new insights, which may influence how Chloé’s viewers read and interpret this iconic Melbourne artwork.

-

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, “Introduction,” in World of Myths: The Legendary Past (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2004), 2:vi. ↩

-

Stephen Knight, The Politics of Myth (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2015), 1. ↩

-

Marina Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981), 3. ↩

-

Ibid., 9. ↩

-

Richard R. Brettell, French Salon Artists 1800–1900 (New York: The Art Institute of Chicago and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987), 3. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Claude Vento, “Jules Lefebvre,” in Les Peintres de la Femme (Paris: E. Dentu, 1888), 304. ↩

-

Tim Fischer, Maestro John Monash: Australia’s Greatest Citizen General (Clayton: Monash University Publishing), 88. ↩

-

NSW Government, State Archives and Records: 17 September 1879–Sydney International Exhibition, accessed July 14, 2019, records.nsw.gov.au/archives/magazine/onthisday/17-september-1879. ↩

-

The Official Record of the Sydney International Exhibition 1879 (Sydney: Thomas Richards, Government Printer, 1881), 458. ↩

-

Stephanie Holt, “Chloé: A Curious History,” in Strange Women: Essays in Art and Gender, ed. J. Hoorn (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1994), 115–134. ↩

-

“The Picture Galleries. The French Court,” Argus, October 28, 1880, 34, accessed July 15, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

“The Vital Statistics of Victoria. Population.” See “Part III. of the Statistical Register of the Colony of Victoria for 1880 deals with the vital statistics. This return gives the total population as 850,343, the figure having been corrected in accordance with the latest census,” Argus, December 5, 1881, 9, accessed July 15, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Australia. Parliament of Victoria. 1881. Melbourne International Exhibition, 1880–81: Final Report of the Proceedings of the Commissioners for the Melbourne International Exhibition 1880, Together with a Statement of Accounts (Melbourne: John Ferres, Government Printer, 1881), accessed July 15, 2019, https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/papers/govpub/VPARL1881No27.pdf. ↩

-

“Trial of Edward Kelly,” Argus, October 29, 1880, 6, accessed August 15, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Ian Jones, Ned Kelly [A Short Life] (Sydney: Hachette, 1995/2008), 367. ↩

-

Geoffrey Robertson, Reflections of a Race Apart (North Sydney: Random House, 2013), 21–25. ↩

-

Graham Seal, “Ned Kelly: The Genesis of a National Hero,” History Today 30, no. 11 (November 1980): 9–15. ↩

-

Jones, Ned Kelly, 263–64. ↩

-

Ibid., xvi. ↩

-

Ibid., 263–64. ↩

-

Lucy H. Hooper, “From Abroad,” Appletons’ Journal: A Magazine of General Literature 15, no. 360 (February 12, 1876): 220–21. University of Michigan Library. ↩

-

Colette E. Wilson, Paris and the Commune, 1871–1878 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 2. ↩

-

Hooper, “From Abroad,” 220–21. ↩

-

Jones, Ned Kelly, 263–64. ↩

-

Hooper, “From Abroad,” 220–21. ↩

-

Wilson, Paris and the Commune, 6. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Penelope Ingram, “Representing the Irish Body: Reading Ned’s Armor,” Antipodes 20, no. 1 (June 2006): 12–19, accessed July 17, 2019, Informit. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Jones, Ned Kelly, 324. ↩

-

Lucy H. Hooper, “From Abroad,” Appletons’ Journal: A Magazine of General Literature 13, no. 360 (February 12, 1876): 220–21. University of Michigan Library. ↩

-

“Il visite souvent vos paisibles rivages … / souvent j'écoute, et l'air, qui gémit dans vos bois, /

A mon oreille au loin vient apporter sa voix. (A. Chénier, Idylles.)” (He often visits your peaceful shores … / I often listen, and the air, which whispers in your woods / Brings his voice to my ear from afar.) See Salon de 1875, “1298 – Chloé” (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1875), 189, accessed July 16, 2019,

Gallica. André Chénier, “Mnasyle et Chloé,” in Poésies de André Chénier, (Paris: Charpentier, 1882), 86-82. ↩

-

Frances Borzello, The Artist’s Model (London: Junction Books, 1985), 5. ↩

-

“Victoria,” see “Tuesday, May 1. The trustees of the Public Library met yesterday and decided by 8 votes to 3 to open the Museum and Picture Gallery on each Sunday in May between 1.30 and 5 p.m.,” Australian Town and Country Journal, May 5, 1883, accessed July 23, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

National Gallery of Victoria, Narratives, Nudes and Landscapes: French 19^th^ Century Art, Exhibition Catalogue (Melbourne: National Gallery of Australia, 1995), n. p. ↩

-

Holt, “Chloé,” 115–34. ↩

-

“Tuesday, May 29, 1883,” Argus, May 29, 1883, 4–5, accessed July 23, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Holt, “Chloé: A Curious History,” 134. ↩

-

“Dr. Jefferies on Gambling,” Christian Colonist, October 8, 1886, 2, accessed July 25, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

“Indecent Pictures and Obscene Books. The Duty of Government. Views of the Reverend B. Butchers,” Herald, February 17, 1887, 2, accessed July 25, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The Colony of Victoria was established on July 1, 1851. “Victorians were ecstatic about their political separation from New South Wales and a healthy competition between the two states and capital cities continues to this day,” see Separation of NSW and Victoria, National Museum Australia website, accessed 14 February, 2020, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/separation-of-nsw-and-victoria. ↩

-

Gerald L. Fischer, Chloé in Adelaide (Lyndoch: The Pump Press, 1985). ↩

-

B. Butchers, “A Visitor’s Protest. To the Editor,” Evening Journal, September 30, 1887, 3, accessed July 29, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“The Contributor. Lay Sermons No. XIII. Chloé. [By the Brothers Nemo.],” South Australian Weekly Chronicle, April 19, 1884, 5, accessed July 29, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Butchers, “A Visitor’s Protest,” 3, accessed July 29, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

“The Contributor. Lay Sermons-No. XIII. Chloé. [By the Brothers Nemo.].” ↩

-

Holt, “Chloé: A Curious History,” 130. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Frances Borzello, The Artist’s Model (London: Junction Books, 1982), 137. ↩

-

Ibid., 138. ↩

-

George Moore, Confessions of a Young Man, ed. Susan Dick (London: William Heinemann, [1888] 1972), 129. ↩

-

Ibid.; Adrian Frazier, George Moore 1852–1933 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000), 489n. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

1. George Moore, Hale and Farewell! Vale (London: William Heinemann [1914] 1933), 69–72. 2. Joseph Hone, The Life of George Moore (London: Victor Gollanz, 1936), 51–52. ↩

-

Moore, Hale and Farewell! Vale, 69–70. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Lucy H. Hooper, “From Abroad,” Appletons’ Journal: A Magazine of General Literature 13, no. 360 (February 12, 1876): 220–21. University of Michigan Library. ↩

-

Lucy H. Hooper, “The Salon of 1875. First Paper,” The Art Journal (1875–1887), New Series 1875, 1:188–190. ↩

-

Lucy H. Hooper, “Paris Letters,” Appletons’ Journal: A Magazine of General Literature 13, no. 324 (June 5, 1875): 731–732. University of Michigan Library. ↩

-

The location of the original painting is unknown. See entry for En avant, Emile Pierre Betsellère in Albums des salons du XIXe siècle ; salon de 1875, Archives Nationales: Album de photographies des œuvres achetées par l'Etat intitulé : "Direction des Beaux-Arts. Ouvrages commandés ou acquis par le Service des Beaux-Arts. Salon de 1875. Photographié par G. Michelez". Œuvres exposées au salon annuel organisé par le Ministère de l'Instruction publique, des Cultes et des Beaux-Arts (Direction des Beaux-Arts), en 1875, au Palais des Champs-Elysées à Paris. Tirage photographique sur papier albuminé représentant : - "En avant !", tableau par Emile Pierre Betsellère, No 191. (Album of photographs of works purchased by the State entitled: "Direction of Fine Arts. Works commissioned or acquired by the Service of Fine Arts. Salon of 1875. Photographed by G. Michelez". Works exhibited at the annual fair organized by the Ministry of Public Instruction, Worship and Fine Arts (Direction des Beaux-Arts), in 1875, at the Palais des Champs-Elysées in Paris.

Photographic print on albumen paper representing: - "En avant!", Painting by Emile Pierre Betsellère, No 191,) accessed August 6, 2019, http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/public/mistral/caran_fr?ACTION=CHERCHER&FIELD_98=LBASE&VALUE_98=AR300860. ↩ -

Ibid. ↩

-

1. Hooper, “From Abroad,” 220–21. 2. John Milner, The Studios of Paris: The Capital of Art in the Late Nineteenth Century (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988), 127. ↩

-

Ibid., 1. ↩

-

Katharine Cooper, and Emma Short, eds., “Introduction,” The Female Figure in Contemporary Historical Fiction (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 3. ↩

-

Hooper, “From Abroad,” 220–21. In Europe, during the nineteen-century, “women would scrape the heads off perhaps one hundred matches, dissolve them in coffee, and drink the brew. In Sweden between 1851 and 1903 there are on record over fourteen hundred cases of phosphorus poisoning in attempted abortion, the victim surviving in only ten cases,” see Edward Shorter, Women’s Bodies: A Social History of Women’s Encounter with Health, Ill-Health and Medicine (Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1991), 211. Until the early twentieth century, phosphorus was still used as an abortifacient, and was “generally taken in the form an infusion of the heads of the phosphorus matches.” See: Herman Ploss, Max Bartels, and Paul Bartels, Woman: An Historical Gynaecological and Anthropological Compendium Volume Three, ed. Eric John Dingwall (London: William Heinemann, 1935), 520. ↩

-

“Chloé: Young and Jackson Hotel, Melbourne,” Young and Jackson Hotel website, accessed July 2, 2014, [https://web.archive.org/web/20140702012826/http://www.youngandjacksons.com.au/downloads/Chloé\_history.pdf]. ↩

-

Hooper, “From Abroad,” 220–21. ↩

-

Bertrand Taith, Citizens and Wars: France in Turmoil 1870–71 (Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2001), 21. ↩

-

Hooper, “From Abroad,” 220–21. ↩

-

Between 1874 and 1876 the President of France and his Prime Minister, the Duc de Broglie, were enacting a regime of moral order, particularly against women who were deemed too “emancipated” and were suspected of being former-Communards. Marie-Patrice MacMahon (1808–1893) was from a family of Irish aristocrats who had been exiled to France in the 18^th^ century. See Charles Sowerine, France Since 1870: Culture, Politics and Society (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2001), 30. ↩

-

Carolyn J. Eichner, Women in the Paris Commune: Surmounting the Barricades (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004), 69. ↩

-

Ibid., 70. ↩

-

David Ross, “Ethel–100 Years Young,” Jules Lefebvre Curatorial Research File, n.d., Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. ↩

-

John Lahey, “A Special Relationship with Chloé,” Age, June 9, 1989, 5, Jules Lefebvre Curatorial File, Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. ↩

-

George Moore, Confessions of a Young Man, ed. Susan Dick (London: William Heinemann, [1888] 1972), 129. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“The Real Chloé Story,” Australasian Post, August 8, 1957, 17, National Library of Australia, Canberra. ↩

-

Lahey, “A Special Relationship with Chloé,” 5. ↩

-

Until 1956, the saloon bar at Young and Jackson Hotel where Chloé hung was an exclusively male environment. 1. See “Men, be prepared for the ‘new look’ at Young and Jackson’s … for the first time in the hotel’s history barmaids are behind the counter. RIGHT UNDER CHLOÉ’S EYES … Three barmaids served during last night’s rush, backed up by two or three barmaids in the saloon bar,” in “Chloé watches over Y & J’s barmaids,” Argus, July 3, 1956, accessed August 6, 2019, Trove. 2. See “Once upon a time, not even a suffragette would have dared to enter the bar at Young and Jackson’s hotel, Melbourne, to view the famous nude, Chloé,” in “Chloé Meets the Girls,” Australasian Post, June 1, 1967, 14–15. ↩

-

Cafram, “‘Chloé’–Queen of the Bar Room Wall,” H2G2 website, accessed February 10, 2020, https://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A950159. ↩

-

Peter James Nicholson (Text), and Howard William Steer (Illustrations), “Legendary Nude–Chloé,” in Just what the Doctor Ordered! A Guide to the Australian Idiom (Desolation Bay: Watermark Publishing, 2015), 191. ↩

-

Claude Vento, “Jules Lefebvre,” in Les Peintres de la Femme, (Paris : E. Dentu, 1888), 301–33. ↩

-

Jules Joseph Lefebvre, La Cigale (1872), National Gallery of Victoria, International Paintings, see https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/76694/. ↩

-

Jules Claretie, Peintres and Sculpteurs Contemporains, Series 2 (Paris: Librairie des Bibliophiles, 1884), 345–67. ↩

-

René François Armand Prudhomme (1839–1907). Sully Prudhomme was a poet and essayist. His poetic works include Impressions de la Guerre (1870) and La France (1874), see “Sully Prudhomme–Biographical,” The Nobel Prize website, accessed August 7, 2019, https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1901/prudhomme-bio.html. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

See Salon de 1875, “Lefebvre (Jules) … 1297 – Rêve — Et … le rêve se dissipa dans les vapeurs du matin. (Ossian.) (And … the dream dissipated in the morning vapours. (Ossian.)” (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1875), 189, accessed July 16, 2019, Gallica. ↩

-

Original text: “Ossian n'est-il pas un des bardes qu’affecte l'impériale rengaine? Je soupçonne donc M. Lefebvre … qui fit l'an dernier un si méchant bruit, je le soupçonne d'avoir comme involontairement symbolise en une facile et saisissante allégorie l'évanouissement lent, mais authentique, de rêve bonapartiste.” Mario Proth, Voyage au pays des peintres, Salon de 1875 (Paris: Chez Henri Vaton, Libraire, 1875), 20–21. ↩

-

Victoria Henshaw, “James Macpherson and his Contemporaries: The Methods and Networks of Collectors of Gaelic Poetry in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 39, no. 2 (June 2016): 197–209, Wiley Online Library, accessed August 8, 2019, [https://doi.org/10.1111/1754-0208.12392]. ↩

-

Colin Smethurst, “Chateaubriand’s Ossian,” in The Reception of Ossian in Europe, ed. Howard Gaskill (London: Bloomsbury, 2004), 126–142, accessed August 8, 2019, ProQuest Ebook Central. ↩

-

David Hesse, Warrior Dreams: Playing Scotsmen in Mainland Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014), 50. ↩

-

Original text: “M. Jules Lefebvre, ex-professeur et portraitiste de celui qui ne sera jamais Napoléon IV, est un des jeunes talents que l'empire n'a, je l'espère, que momentanément gâtés!” Proth, Voyage au pays des peintres, 20–21. ↩

-

“Jules Claretie,” n.d., Académie Français website, accessed August 7, 2019, http://www.academie-francaise.fr/les-immortels/jules-claretie. ↩

-

The original text reads: “Au Salon de 1874, Jules Lefebvre exposait le portrait du prince impérial. Oh ! les sottises de la politique ! Ce que nous vîmes surtout alors, dans cette peinture, ce n'était point la peinture même, c`était une manifestation de parti, et nous jugions mal, puisque nous ne jugions pas l'œuvre intrinsèquement. Je voudrais revoir aujourd'hui le portrait de l'adolescent qui devait mourir en héros au Zululand. Lefebvre en a conservé, chez lui, une étude, - la tête seule - et c'est un chef-d’œuvre. L'année suivante, Jules Lefebvre exposait une Chloé d'un modèle exquis et une fantaisie dont retrouvais, l'autre jour, l'esquisse chez François Coppée : c'est le Rêve. “ Claretie, Peintres and Sculpteurs, 355. Concerning Bonapartism: “As a regime type, at least in its first two incarnations, Bonapartism is synonymous with the seizure of power in a coup d’état … and with the formation of a hereditary empire, monarchy in a new key.” See Isser Woloch, “From Consulate to Empire: Impetus and Resistance,” in Dictatorship in History and Theory: Bonapartism, Caesarism and Totalitarianism, ed. Peter Baehr and Melvin Richter (Washington, D. C.: German Historical Institute & Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 28–52. ↩

-

Claretie, Peintres and Sculpteurs, 350. ↩

-

Original text: “Au moment où le prince pose pour Jules Lefebvre, il vit les derniers jours d’une enfance heureuse et insouciante dans ce palais de Saint-Cloud qui sera son dernier séjour français et qu’il ne reverra jamais ensuite. L’artiste a fait de l’adolescent un portrait intimiste, d’une grande profondeur psychologique. Le visage est sérieux, le sourire a déserté ses lèvres, le regard est triste et nostalgique, comme si le fils de Napoléon III était conscient de la situation. Il tourne la tête vers la gauche du tableau, derrière lui, vers le souvenir déjà lointain des fastes de l’empire. ” Alain Galoin, “Portrait du Prince Impérial,” L’Histoire par L’Image website, 2005, accessed February 12, 2020, https://www.histoire-image.org/etudes/portrait-prince-imperial?=603. ↩

-

Sudhir Hazareesingh, “Bonapartism as the Progenitor of Democracy: The Paradoxical Case of the French Second Empire,” in Dictatorship in History and Theory: Bonapartism, Caesarism and Totalitarianism, ed. Peter Baehr and Melvin Richter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 120–52. ↩

-

Charles Sowerine, France Since 1870: Culture, Politics and Society (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001), 29–30. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Frances Scarfe, André Chénier: His Life and Work 1762–1794. (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1965), 346–367. ↩

-

Heather M. Bennett, “Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France’s Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880,” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2013, 22–30. ↩

-

Claude Vento, “Jules Lefebvre,” in Les Peintres de la Femme (Paris: E. Dentu, 1888), 304–33. 2. Edward Blakeman, Tafanel: Genius of the Flute (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 50. ↩

-

George Moore, Confessions of a Young Man (Montreal and London: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1972), 110–111. ↩

-

François Pédron, Les Rapins L’âge d’or de Montmartre: Of Paupers and Painters–Studios of Montmartre Masters, translated by Jack Russell, photos by Stéphane Pons (Graulhet: Escourbiac Printing House, 2008), 52. ↩

-

Gabriel P. Weisberg, “The Women of the Académie Julian: The Power of Professional Emulation,” in Overcoming all Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian, ed. Gabriel P. Weisberg and Jane R. Becker (New York: The Dahesh Museum and New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 38–39. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

National Trust of Australia (Victoria), Submission Concerning Young and Jackson’s Hotel, July 13, 1988, 6. ↩

-

“Much-travelled Bottle. Castlemaine Soldier’s Message. Interesting Incident,” Castlemaine Mail, January 18, 1918, 2, accessed August 12, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

“The Week,” Table Talk, February 13, 1919, 4, accessed August 15, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

“Chloé ‘In the Altogether’,” Recorder, May 12, 1934, 3, accessed August 16, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

“‘It’s a Long Way to Bonegilla:’ Big March To-Day,” Argus, September 23, 1940, 5. Trove. On February 2, 1942, B and C Companies of the 2/21st Australian Infantry Battalion were massacred by Japanese forces at Laha Airfield on the Indonesian island of Ambon, see Australian War Memorial website, accessed August 20, 2019, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U56064. ↩

-

Peter Graeme, “Seein’ Chloé,” Western Mail, May 3, 1945, 15, accessed August 20, 2019, Trove. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Graeme, “Seein’ Chloé.” ↩

-

Ambon, Indonesia. Prior to August 17, 1945, the date Indonesian independence was proclaimed, Ambon was an island “in what was then the Dutch East Indies.” See Roger Maynard, Ambon: The Truth About One of the Most Brutal POW Camps in World War II and the Triumph of the Aussie Spirit (Sydney: Hachette, 2014), xiv; xi. ↩

-

“‘It’s a Long Way to Bonegilla:’ Big March To-Day,” 5. ↩

-

Maynard, Ambon, xvi. ↩

-

Ibid., xii. ↩

-

Ibid., xiii. ↩

-

Ibid., xv–xvi. ↩

-

Ibid., 218–19. ↩

-

Ibid., 220. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Inga Clendinnen, “The History Question: Who Owns the Past?” Quarterly Essay 23 (2016): 5–6. ↩

-

Ibid., 7. ↩

Dr Katrina Kell is an Honorary Postdoctoral Associate at Murdoch University. Her research explores the untold female history of Jules Joseph Lefebvre’s nude painting Chloé, one of Melbourne’s celebrated cultural icons. She is an award-winning writer of short fiction and young adult literature, and in March 2020, she was awarded an Australian Society of Author’s Mentorship for her historical novel manuscript “Anatomy of an Artist’s Model.”

Bibliography

- Académie Français Website, n.d. “Jules Claretie.” http://www.academie-francaise.fr/les-immortels/jules-claretie.

- Argus. “The Picture Galleries. The French Court.” October 28, 1880. Trove.

- Argus. “Trial of Edward Kelly.” October 29, 1880. Trove.

- Argus. “The Pictures Which Have Gained Awards.” March 16, 1881. Trove.

- Argus. “The Vital Statistics of Victoria. Population.” December 5, 1881. Trove.

- Argus. “Tuesday, May 29, 1883.” May 29, 1883. Trove.

- Argus. “It’s a Long Way to Bonegilla:” Big March To-Day.” September 23, 1940. Trove.

- Argus. “Chloé Watches Over Y & J’s Barmaids.” July 3, 1956, 3. Trove.

- Australasian Post. “The Real Chloé Story.” August 8, 1957. Trove.

- Australasian Post. “Chloé Meets the Girls.” June 1, 1967, 14–15. Culture Victoria.

- Australia. Parliament of Victoria. 1881. Melbourne International Exhibition, 1880–81: Final Report of the Proceedings of the Commissioners for the Melbourne International Exhibition 1880, Together with a Statement of Accounts. Melbourne: John Ferres, Government Printer, 1881.

- Australian Town and Country Journal. “Victoria. Tuesday, May 1.” May 5, 1883 Trove.

- Bennett, Heather M. “Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France’s Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871–1880.” PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2013.

- Blakeman, Edward. Tafanel: Genius of the Flute. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Borzello, Frances. The Artist’s Model. London: Junction Books, 1982.

- Brettell, Richard R. French Salon Artists 1800–1900. New York: The Art Institute of Chicago and Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987.

- Butchers, B. “A Visitor’s Protest. To the Editor.” Evening Journal, September 30, 1887. Trove.

- Cafram. H2G2 Website. “‘Chloé’–Queen of the Bar Room Wall.” [2003] 2011.

- Castlemaine Mail. “Much-travelled Bottle. Castlemaine Soldier’s Message. Interesting Incident.” January 18, 1918. Trove.

- Chénier, André. Poésies de André Chénier. Paris: Charpentier et Cie. Christian Colonist. 1886. “Dr. Jefferies on Gambling.” October 8, 1886. Trove.

- Claretie, Jules. Peintres and Sculpteurs Contemporains, Volume 2. Paris: Librairie des Bibliophiles. 1884.

- Clendinnen, Inga. “The History Question: Who Owns the Past?” Quarterly Essay 23 (2006): 1–72. Informit.

- Cooper, Katherine, and Emma Short. “Introduction”. The Female Figure in Contemporary Historical Fiction, edited by Katherine Cooper and Emma Short, 3. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Eichner, Carolyn J. Women in the Paris Commune: Surmounting the Barricades. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe. “Introduction.” In World of Myths: The Legendary Past Volume Two. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2004.

- Fischer, Gerald Lyn. Chloé in Adelaide. Lyndoch: The Pump Press, 1985.

- Fischer, Tim. Maestro John Monash: Australia’s Greatest Citizen General. Clayton: Monash University Publishing, 2014.

- Frazier, Adrian. George Moore 1852–1933. New Haven and London: Yale, 2000.

- Galoin, Alain. “Portrait du Prince Imperial.” L’Histoire par L’Image website, 2005. https://www.histoire-image.org/etudes/portrait-prince-imperial?=603.

- Graeme, Peter. “Seein’ Chloé.” Western Mail, May 3, 1945. Trove.

- Hazareesingh, Sudhir. “Bonapartism as the Progenitor of Democracy: The Paradoxical Case of the French Second Empire.” In Dictatorship in History and Theory: Bonapartism, Caesarism and Totalitarianism, edited by Peter Baehr and Melvin Richter, 129–152. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Henshaw, Victoria. “James Macpherson and His Contemporaries: The Methods and Networks of Collectors of Gaelic Poetry in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 39, no. 2 (June 2016): 197. Dictatorship in History and Theory: Bonapartism, Caesarism and Totalitarianism 209. [https://doi.org/10.1111/1754-0208.12392].

- Herald. “Indecent Pictures and Obscene Books. The Duty of Government. Views of the Reverend B. Butchers.” February 17, 1887. Trove.

- Hesse, David. Warrior Dreams: Playing Scotsmen in Mainland Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014.

- Holt, Stephanie. “Chloé: A Curious History.” In Strange Women: Essays in Art and Gender, edited by J. Hoorn, 115–134. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1994.

- Hone, Joseph. The Life of George Moore. London: Victor Gollancz, 1936.

- Hooper, Lucy H. “The Salon of 1875. First Paper.” The Art Journal (1875–1887), New Series 1:188–190, 1875. https://doi.org/10.2307/20568711.

- Hooper, Lucy H. “Paris Letters.” Appletons’ Journal: A Magazine of General Literature 13, no. 324 (June 5, 1875): 731–732. University of Michigan Library.

- Hooper, Lucy H. “From Abroad.” Appletons’ Journal: A Magazine of General Literature 15, no. 360 (February 12, 1876): 220–21. University of Michigan Library.

- Ingram, Penelope. “Representing the Irish Body: Reading Ned’s Armor.” Antipodes 20, no. 1 (June 2006): 12–19.

- Jones, Ian. Ned Kelly [A Short Life]. Sydney: Hachette, [1995] 2008.

- Knight, Stephen. The Politics of Myth. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2015.

- Lahey, John. “A Special Relationship with Chloé.” Age, June 9, 1989. Jules Lefebvre Curatorial File, Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria.

- Maynard, Roger. Ambon: The Truth about One of the Most Brutal POW Camps in World War II and the Triumph of the Aussie Spirit. Sydney: Hachette, 2014.

- Milner, John. The Studios of Paris: The Capital of Art in the late Nineteenth Century. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Moore, George. Confessions of a Young Man. Edited by Susan Dick. London: William Heinemann, (1888) 1972.

- Moore, George. Hale and Farewell! Vale. London: William Heinemann, [1914] 1933.

- National Gallery of Victoria. Narratives, Nudes and Landscape: French 19th-Century Art. Exhibition Catalogue. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, 1995.

- National Trust of Australia (Victoria). Submission Concerning Young and Jackson’s Hotel. July 13, 1988, 7.

- Nicholson, Peter James (Text), and Howard William Steer (Illustrations). “Legendary Nude–Chloé.” In Just What the Doctor Ordered! A Guide to the Australian Idiom, 191. Desolation Bay: Watermark Publishing, 2015.

- NSW Government, State Archives and Records: 17 Sep 1879–Sydney International Exhibition. records.nsw.gov.au/archives/magazine/onthisday/17-september-1879.

- Pédron, François. Les Rapins L’âge d’or de Montmartre: Of Paupers and Painters – Studios of Montmartre Masters, translated by Jack Russell, photos by Stéphane Pons. Graulhet: Escourbiac Printing House, 2008.

- Ploss, Herman, Max Bartels, and Paul Bartels. Woman: An Historical Gynaecological and Anthropological Compendium Volume Three. Edited by Eric John Dingwall. London: William Heinemann, 1935.

- Proth, Mario. Voyage au pays des peintres, Salon de 1875. Paris: Chez Henri Vaton, Libraire, 1875.

- Recorder. “Chloé “In the Altogether”.” May 12, 1934. Trove.

- Robertson, Geoffrey. Reflections on a Race Apart. North Sydney: Random House, 2013.

- Ross, David. “Ethel–100 Years Young.” Jules Lefebvre Curatorial Research File, Shaw Research Library, National Gallery of Victoria, n.d.

- Salon de 1874. Exhibition Catalogue. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, Gallica, 1875.

- Scarfe, Francis. André Chénier: His Life and Work 1762–1794. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1965.

- Seal, Graham. “Ned Kelly: The Genesis of a National Hero.” History Today 30, no. 11 (November 1980): 9–15.

- Shorter, Edward. Women’s Bodies: A Social History of Women’s Encounter with Health, Ill-Health and Medicine. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1991.

- Smethurst, Colin. “Chateaubriand’s Ossian.” In The Reception of Ossian in Europe. Edited by Howard Gaskill, 126-142. London: Bloomsbury, 2004.

- South Australian Weekly Chronicle. “The Contributor. Lay Sermons-No. XIII. Chloé. [By the Brothers Nemo.].” April 19, 1884. Trove.

- Sowerine, Charles. France since 1870: Culture, politics and society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

-Table Talk. “The Week.” February 13, 1919. Trove. - Taithe, Bertrand. Citizens and Wars: France in turmoil 1870–1871. Oxon & New York: Routledge, 2001.

- The Official Record of the Sydney International Exhibition 1879. Sydney: Thomas

- Richards, Government Printer, 1881.

- Vento, Claude. “Jules Lefebvre.” In Les Peintres de la Femme. Paris: E. Dentu, 1888.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P. The Women of the Académie Julian: The Power of Professional Emulation.” In Overcoming all Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian, edited Gabriel P. Weisberg and Jane R. Becker, 13–67. New York: The Dahesh Museum and New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 1999.

- Warner, Marina. Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981.

- Wilson, Colette E. Paris and the Commune, 18712007.78. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007.

- Woloch, Isser. “From Consulate to Empire: Impetus and Resistance.” In Dictatorship in History and Theory: Bonapartism, Caesarism and Totalitarianism,edited by Peter Baehr and Melvin Richter, 28–52. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. .

- Young and Jackson Hotel website. “Chloé: Young and Jackson Hotel, Melbourne.” Website has expired but may be accessed via this internet archive:* [https://web.archive.org/web/20110218133636/http://www.youngandjacksons.com.au/]